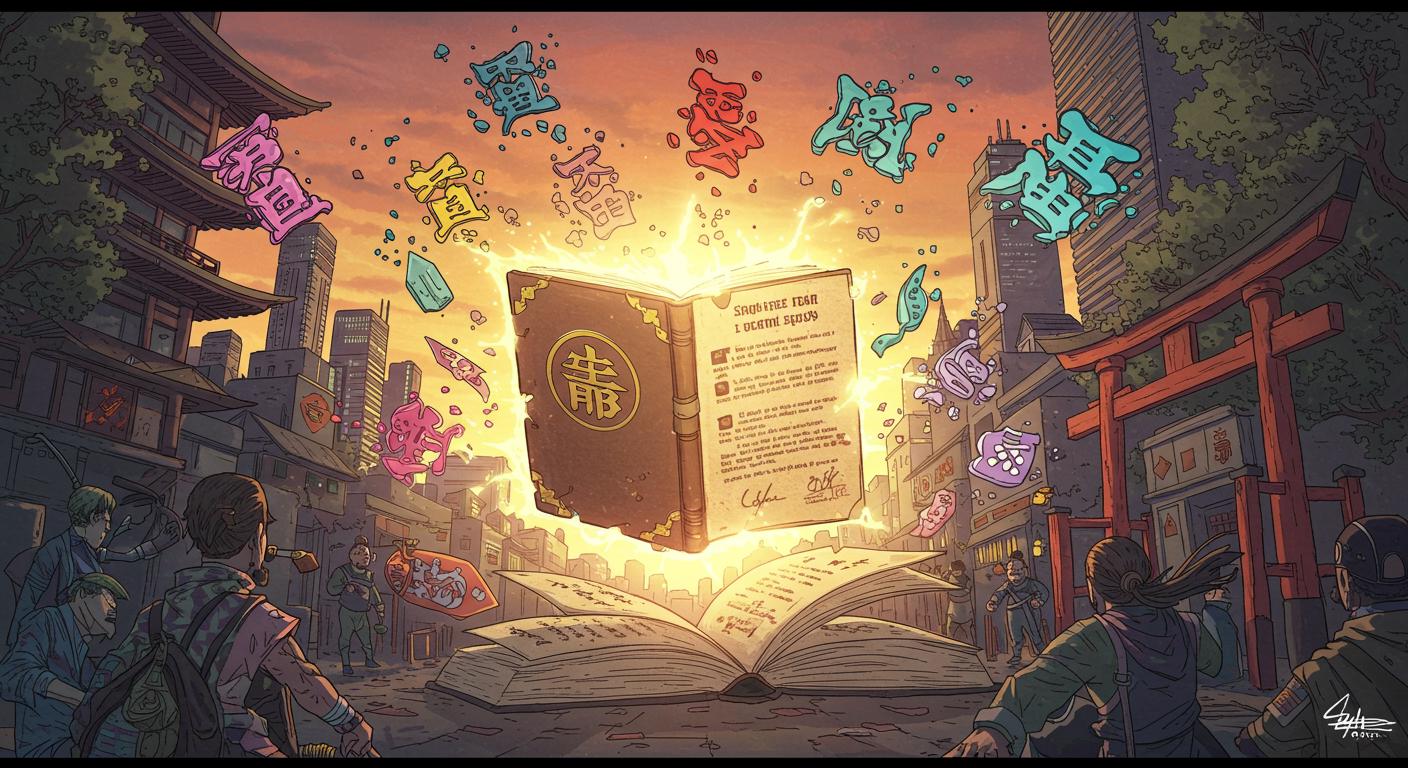

If you’ve ever entertained the image of a tiny Pikachu answering roll call at a Japanese preschool—officially, at least—expect those lightning bolts to be short-circuited. As chronicled in a Sri Lanka Guardian report, Japan has formalized its crackdown on kira-kira (“flashy”) baby names. The days of mingling with children named after Pokémon, desserts, or ancient rulers may now be mostly relegated to fiction and, perhaps, family pets.

Kanji, Creativity, and Official Second Thoughts

Japanese naming traditions have long resembled linguistic freestyle, courtesy of the kanji writing system: a single set of characters can have a smorgasbord of possible readings. For ambitious or whimsical parents, this once meant a chance to launch their child into society with names like Shiizaa (Caesar), Raburi (Lovely), Purin (Pudding), or the now-unwelcome Pikachu—sometimes regardless of the original meaning of the kanji. According to information detailed by the Guardian, this resulted in registries sporting a diverse collection of monikers, ranging from Eren (crafted for “Eternal Love”) to the aforementioned Pokémon favorite.

Not that this is a sudden intervention. As referenced in the outlet’s coverage, Japanese officials have intervened in outlandish naming before: a 1994 case famously denied the registration of “Akuma”—the Japanese word for “devil”—for a newborn, despite names with divine associations passing muster.

How the Rules Are Changing

Under the newly introduced policy, parents must now provide the precise pronunciation of their child’s kanji-based name at registration. Equally significant, proposed names will face review by government officials, who have discretion to reject any moniker with “extreme readings” or those not considered in a child’s best interests, as outlined in the Sri Lanka Guardian. The bar for what counts as “too extreme” isn’t rigidly defined, but the central criterion—child welfare—comes into clear focus. The era of using kanji for, say, “eternal love” and pronouncing it as “Chainsaw,” is largely over.

Prior interventions, as documented by the Guardian, suggest the government has long wrestled with where to draw the line: is novelty in a name a gift or a burden? Ojisama Akaike (Mr. Prince) stands out, a real case where a young man reportedly changed his name to Hajime (“beginning”) after years of disbelief from others—a less-than-glamorous legacy for the original title.

Between Self-Expression and the Social Fabric

Opponents of the policy, including Japan’s liberal-leaning Asahi Shimbun, worry about linguistic stagnation. The Sri Lanka Guardian cites the newspaper’s warning that: “Names and readings of names written in kanji, like words in general, change with the times. Restrictions … should be limited to the absolute minimum.” Supporters, meanwhile, argue that these new standards will protect children from unnecessary embarrassment and, perhaps, medical mishaps; a 2015 study referenced in the Guardian tied kira-kira names to a higher rate of emergency room visits—though whether hyper-vigilant or neglectful parenting is to blame remains unclear.

With Japan’s population declining and the number of deaths recently outpacing births at a two-to-one ratio, the timing of this regulatory pushup could seem questionable. Still, for some, making playground introductions a little less absurd could be reason enough. After all, as the Guardian notes, not every child dreams of being known as Prince or Pudding long past the novelty of babyhood.

Pikachu, Please Wait Outside

Summing up, as the Sri Lanka Guardian observes, names like Pikachu and Caesar are set to leap from bureaucratic oddity to cultural footnote. The future might hold fewer stories of children encountering disbelief at formal events or job interviews, and a little more predictability for government clerks tasked with processing birth certificates.

Will this be the end of whimsical baby-naming in Japan or just a pause before the next creative workaround? Perhaps it’s simply a gentle reminder that what seems charming at birth could echo for decades—sometimes in the form of a puzzled bank teller, and sometimes, thankfully, only as a beloved character on TV.