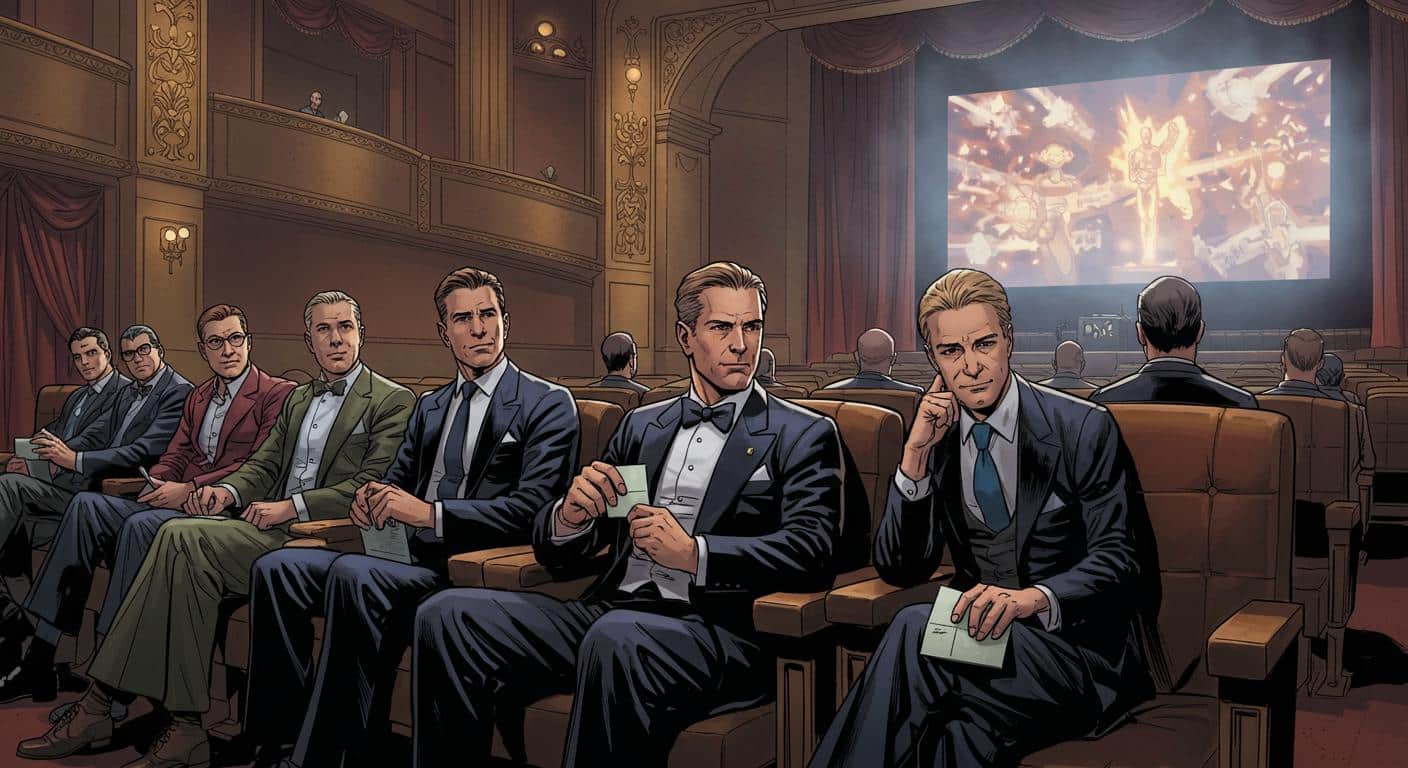

Somewhere out there, an Oscar voter is quietly mourning the end of a cherished ritual: the annual, lightly-performed fib about having seen every nominated film before casting a ballot. This week’s procedural update from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences makes this tradition just a little more difficult, and—according to A.V. Club—the new policy essentially asks voters to do what most people assumed they were already doing: actually watch the films they’re voting on. Hollywood, always full of surprises.

Closing the Curtain on Invisible Voting

The Academy’s change, as described in both A.V. Club and Next Best Picture, means that members must now provide evidence of having watched all the films in a category if they wish to vote on the Oscar for that category. The previous approach, as A.V. Club reminds us, was more of an honor code—voters were “kindly asked” to abstain from categories where their exposure was less than complete. This trust-based system resulted in a stream of anonymous ballots where voters freely confessed to skipping the longer or “boring” nominees, yet still threw their vote into the ring.

Now, things are a bit more official. The Academy will use its Screening Room platform to automatically keep track of films watched, but if a member claims to have viewed a film at a festival, a guild screening, or perhaps in a friend’s suspiciously opulent home theater, they must fill out a form disclosing when and where the magic happened. The Hollywood Reporter, cited by A.V. Club, details how this form is key for anyone watching outside the Academy’s system.

Next Best Picture points out that with over 10,000 voting members, the logistics quickly become daunting. The voting process will hinge on three interconnected systems: the digital screening platform, the submission form for off-platform viewing, and the actual voting ballot. Integrating these, the outlet explains, means only unlocking ballots for voters who’ve officially watched every nominee in that slot—so any “I’ll just vote for the one I know” maneuvers might finally be stifled. Yet, it’s acknowledged that some members may simply hit play in the Academy Screening Room, silence the audio, and go about reorganizing the garage—an ingenious, if questionable, approach impossible to catch short of installing some kind of Oscar-grade eye-tracking device.

New Rules, Old Habits

Next Best Picture, referencing a revealing Variety article, notes the underlying tension: many Oscar voters haven’t always watched the films. While the ASR can see if a file was played, it can’t ensure attention was paid. The outlet floats ideas for greater accountability, such as membership evaluations or even mandatory physical screenings—though the latter would be a herculean feat with so many voters. Still, perhaps there’s some comfort in knowing that even Hollywood’s most self-assured are being nudged back to basics, as reported in both outlets.

A fresh layer of irony, pointed out by the A.V. Club, is that the “long overdue” rule change is newsworthy in the first place. Let’s not pretend “required to watch a movie before voting for its award” is a cutting-edge idea in any other field. Will Oscar campaigners now have to factor in “viewer verification” parties in addition to glossy billboards and elaborate swag?

Inclusivity and Oscars: A New (More Watched) World

Alongside this cinematic homework policy, the Academy issued updates on inclusivity. As detailed by both sources, filmmakers with refugee or asylum status can now submit in the International Feature Film category on behalf of their current country of residence, a move Next Best Picture welcomes as a step toward greater representation. There are new shortlists for Best Cinematography and the Achievement in Casting award, intended to tighten the process and, perhaps, give less established contenders a better shot—if they make it to the point where every voter must watch them, of course.

However, there’s a lingering snag. While voters must see all category nominees to vote in the final round, there’s still no equivalent requirement for the nominating process. As Next Best Picture points out, this creates an odd scenario: films with minimal buzz or limited resources can get overlooked before ballots even demand attention be paid. For categories like Best International Feature, where smaller countries’ entries are typically overshadowed by festival hits with heavyweight backers, it’s a reminder that even the most careful reforms have their loopholes.

One suggestion, as put forward by Next Best Picture, is to expand shortlists or empower curatorial committees—giving more obscure works a fighting chance at being noticed before ultimately landing on the must-watch list for every voter. The hope is that some gems—“How to Make Millions Before Grandma Dies” is cited as a recent example of deserving work—might finally break through.

The Great Watchlist and the Road Ahead

The new system’s practicality may hinge on the patience and honesty of its participants. As noted by Next Best Picture, the technical hurdles around processing viewer forms (and verifying their claims) could create logjams—especially among those notorious for leaving everything until deadline day. The A.V. Club also wonders, with trademark dryness, whether this will truly end the time-honored practice of strategic abstention, where a voter simply chooses not to judge a film out of protest, indifference, or pure convenience.

Still, there’s something oddly heartening about an industry steeped in illusion taking a step—however bureaucratic—toward greater transparency. Will the winners feel more representative, the process more fair? Or will the future simply involve more creative workarounds, with bored voters still finding ways to skirt the edge? As the A.V. Club sums up, it’s ultimately an open experiment: “We’ll see how it all shakes out now that voters can’t choose to abstain from watching certain movies in protest, or for any other reason.”

If nothing else, the new rules guarantee that—at least in theory—every Oscar winner was viewed by all who judged it, even if some eyes wandered to the popcorn bowl now and then. One has to wonder: Will 2026 be the year a surprise dark horse wins, simply because the audience had no choice but to give it a chance? Or should we start bracing for the era of the Academy-mandated double feature?

When even the arbiters of cinematic gold are asked to log their hours, perhaps we can all agree that “just press play” finally means something in Hollywood.