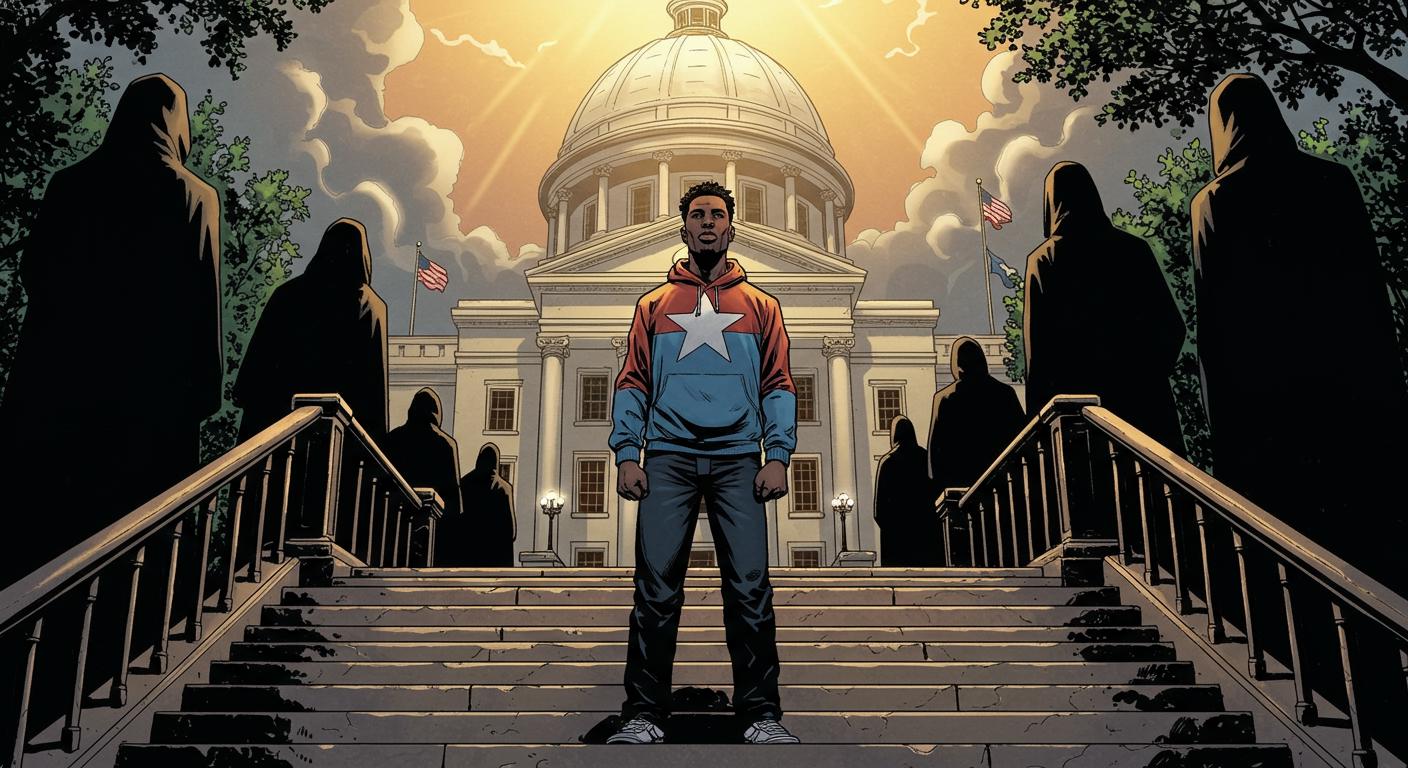

It isn’t often that a U.S. Senate candidate strolls out with a backstory seemingly pulled from a Faulkner novel and calmly says, “I’ve moved on.” But that’s precisely the mood hovering over Mark Wheeler’s bid for Alabama’s soon-to-be-vacant seat. Wheeler, a 32-year-old chemist from Heflin, has had not just one but two immediate family members convicted of murder—a detail given almost offhandedly, sandwiched between endorsements of mass transit and environmental protection. According to an AL.com feature, Wheeler is as matter-of-fact about these violent footnotes as he is about wire safety.

Family Album: True Crime Edition

Described in AL.com’s reporting, Wheeler’s biography reads like a checklist of adversity. When Wheeler was an infant in 1994, his father was sentenced to life for the brutal murder of 16-year-old Lisa Ann Beason; the details, cited from earlier news coverage, are grisly. Then, after Wheeler’s mother remarried, his stepfather was convicted in 2005 (along with two others) for the murder of four people in Cleburne County. Both men remain incarcerated.

Reflecting on these circumstances, Wheeler told AL.com, “I’ve spent a lot of my life around a lot of bad people. Not necessarily bad people but people with bad circumstances. My circumstances have been bad.” The candidate sets aside both denial and melodrama, instead offering what can only be described as a stoic working theory: bad things happen, and you keep moving forward.

Degrees, Wires, and the Democratic Desert

Emerging from a landscape few would envy, Wheeler built a path through science and industry. As noted by AL.com, he earned a bachelor’s degree in chemistry and emergency management at Jacksonville State University and took up a job as a polymer chemist at a wire manufacturer. In his own words, “I am the guy that makes sure that new wire that’s made is not going to burn your house down.” Reassuring as campaign mantras go, if a bit utilitarian.

Wheeler tells the outlet that qualities like perseverance and persistence, honed through what he gently dubs “childhood trauma,” carried him to stability—a narrative that fits neatly into American ideals of bootstrap heroics but still stands out in its extremity. He acknowledges that he didn’t do it alone, crediting positive people along the way.

It’s worth noting, per the article, that Democratic wins on a statewide scale in Alabama are rare events. Wheeler is one of three Democrats vying for Senator Tommy Tuberville’s soon-to-be-vacant seat, and the state hasn’t sent a Democrat to Washington since Doug Jones’s surprising 2017 victory.

Lofty Aims and Uncommon Transparency

So what does a candidate with this sort of background champion from the campaign trail? AL.com reports that Wheeler’s platform includes establishing term limits for both Congress and the Supreme Court, along with banning stock trading by members of Congress. He also proposes policies focusing on clean air and water, professing that his expertise as a chemist gives him unusual insight into environmental risks—he remarks, “I understand what these chemicals can do with our water,” as the outlet highlights.

Healthcare reform features prominently, too: Wheeler told AL.com he supports national health insurance, making the case that a larger shared risk pool would lower costs, and muses, “Every paycheck you get, you’re having Medicare taxes taken out. You’re already paying for it. Why not use it?”

On infrastructure, Wheeler’s vision, detailed in the article, sounds almost futuristic for the rural South: high-speed rail, mass transit, and even the possibility of integrating power, internet, and interstate water lines along new corridors. “There are tons of opportunity there,” he says, optimism peeking out through the practicalities of his professional routine.

Accessibility as a Campaign Shtick

Beyond policy, Wheeler’s formative irritation seems to be government inaccessibility. According to the AL.com report, he voices a complaint familiar to many: elected officials are “like mythical figures. Almost don’t exist.” He contrasts the directness of local government—where the mayor is just a phone call away—with the sphinx-like distance of DC politics and promises to bring transparency, availability, and a touch of small-town sensibility to the marble corridors.

Adversity as Prologue?

Perhaps the most intriguing element is Wheeler’s conscious refusal to let his family’s history dominate his narrative. He acknowledges the facts, uses them as a footnote for resilience, and pivots quickly to what he calls “changing the ties between voters and their representatives.” When asked by AL.com why he bothers running as a Democrat in Alabama’s challenging climate, Wheeler simply says he’s reached a point where, if he doesn’t try to change things, he worries about the world his children will inherit.

The obvious question, of course, is whether voters in Alabama—where family values are not just a catchphrase but often a ballot-box litmus test—will see Wheeler’s personal tragedies as a mark against him, or as proof of unusual grit. Does moving on from a history as turbulent as this make a candidate more relatable or simply raise too many “Wait, what?” moments at the polls?

Wheeler seems content with the facts: his own actions, not his family’s, are what matter. The rest, he leaves to an electorate not known for its fondness for Democratic experiments. Already, his campaign is proof that sometimes, the line between the bizarre and the everyday is thinner than we think. Is Alabama ready to let it blur even further?