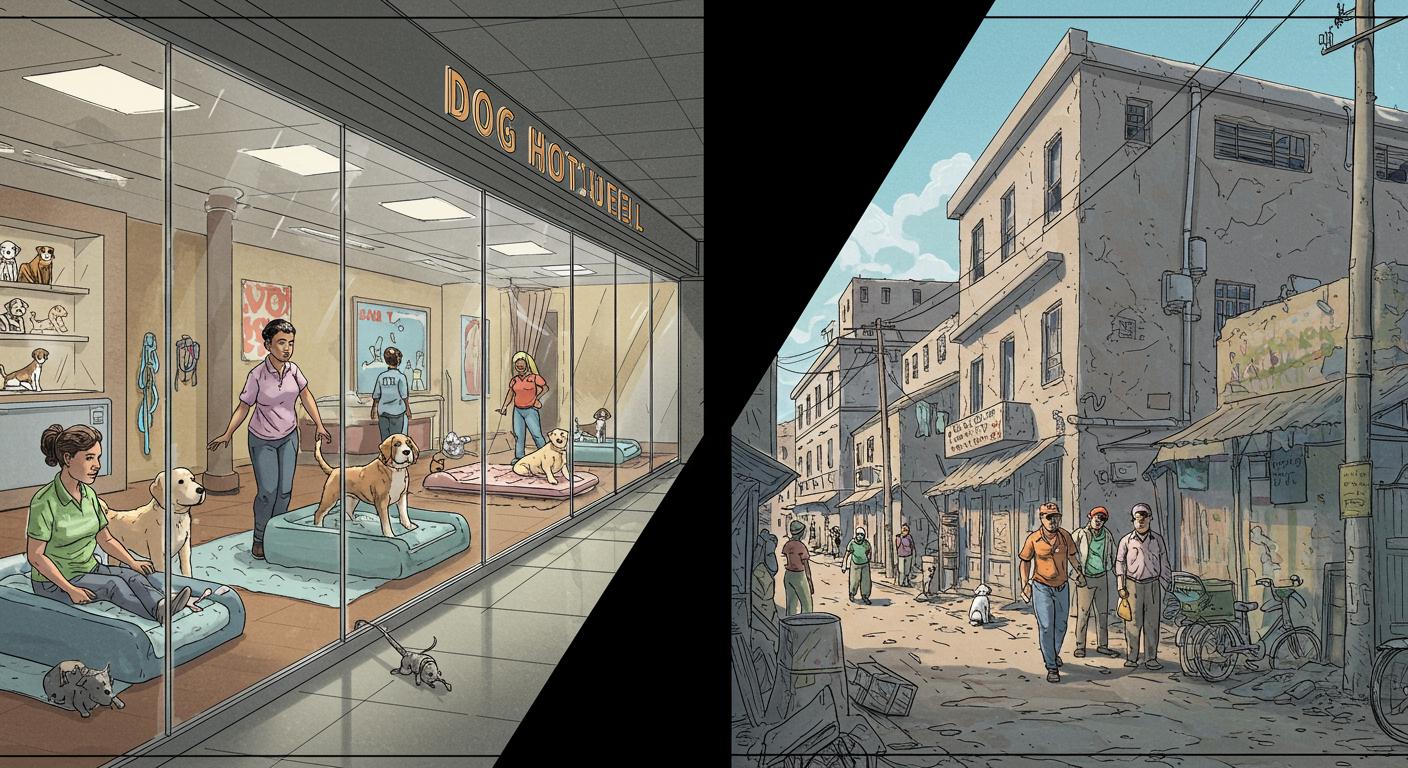

South Africa is a country famous for its wild extremes—geography, history, and, as it turns out, pet amenities. As reported in a recent NPR article, luxury dog hotels are not just a quirky footnote to Cape Town living, but a full-on booming industry. Plush beds. Pool decks. Doggy spa treatments set to meditative soundtracks. It’s the kind of tableau that forces a double-take, especially when just a block away, makeshift tents and desperate poverty dominate the landscape. Doesn’t it make you wonder what a drone shot of this city might reveal—a patchwork of velvet chaise lounges for poodles adjacent to rows of corrugated iron shelters?

Sun Loungers for Dachshunds, Tents for the Homeless

The imagery highlighted by NPR feels almost designed to prod at our sense of incongruity. While a dachshund soaks up the sun on a custom-made lounger at Vienna’s Village luxury dog hotel, barely a mile away, residents of Masiphumelele live tightly packed in ramshackle structures of metal and timber. Above a night shelter for the homeless, the Superwoof Dog Hotel offers a rooftop pool for pups and, for those with a cultivated palate (or owners with a taste for whimsy), “Champaws” from the onsite “Woofbar.” On the day NPR visited, a bulldog named Archie celebrated his birthday with a tennis ball-themed cupcake. If only every dog’s diary included such entries.

It’s not just outsiders who register this cognitive whiplash. Superwoof’s managing director, Bianca Couch, acknowledges the disconnect, admitting to NPR that “in the socioeconomic context of Cape Town, the idea of luxury dog hotels can be ‘jarring.’” The context includes hard numbers: NPR cites a government report from 2024 in which half of all employed South Africans were found to be earning less than R5,200 ($283.26) per month. Yet, day care rates at these hotels run from 210 rand ($11.45) to 410 rand ($22.30) per night—sums that might make a difference elsewhere in the city.

Meanwhile, the opulence continues. The report describes a calendar packed with dog birthday parties, canine weddings complete with confetti and red carpets—a veritable canine society page. Clients might be young professionals without a yard, but their hounds still get to lounge under chandeliers after spa hydrotherapy or reiki treatments at atFrits Dog Hotel, all watched over by livestream camera, just in case separation anxiety is a two-way street. Who knew the “presidential suite” at a dog hotel came with a private TV and gilt-framed pup portraits, as described by the outlet?

The Bubble Effect

Is all this simply frivolity, or is there something more complex at play? Couch tells NPR that Superwoof provides employment for 25 staff and also supports dog adoption programs. AtFrits employs 38 and, as the founder Yanic Klue points out to NPR, runs charity initiatives and programs training marginalized women to create pet clothing—a twist that at least offers a measure of social impact. NPR also notes that it’s not just the ultra-wealthy dropping off their pets: some clients include lawyers, restaurant workers, and young professionals living in flats, as previously reported by the outlet.

Still, the hotel owners themselves sometimes slip into moments of frankness about the contrast. When NPR asked Jayne Le Roux, owner of Vienna’s Village, whether she notices the poverty near her hotel, she responded, “I guess you just don’t see it,” only pausing later to concede, “I suppose we’re in a bit of a bubble.” Is the bubble fragile, or simply a necessary filter when selling wild cherry puppy spritz and mango pet perfume to a clientele eager for distraction?

And how often do doggy Valentine’s Day parties—complete with pink heart-shaped cookies and cubes of watermelon—collide with the realities of unemployment and food insecurity next door? As documented in NPR’s account of a February hotel visit, these juxtapositions are a daily occurrence in Cape Town.

A Nation of Contradictions

In a detail underscored by NPR, Cape Town’s dog hotels appear as flawless dioramas of canine luxury set against a backdrop of the planet’s highest income inequality. Aerial views of the city, as described in the report, reveal the dense sprawl of impoverished townships pressed up against gated housing estates—and near the luxury pet hotels, hundreds of thousands of families wait for adequate housing promised by the state.

For some, as the outlet also notes, these businesses offer essential support. A client and children’s rights lawyer explained to NPR that, without the dog hotel, she wouldn’t be able to own her dog at all due to professional demands. In contrast, critics like Luyanda Mtamzeli from the legal non-profit Ndifuna Ukwazi argue in the report that prioritizing canine comfort over basic human needs exposes a profound lack of political will to address entrenched systemic inequality. Can both these realities coexist, or does one inevitably eclipse the other?

Near the Superwoof building, as barking floats down from the skydeck, Asanda Ncanda—living in a tent below—told NPR he begrudges no one their business. “I love animals, and I would never say they shouldn’t be running their business,” he said, but the psychological sting is real: “What does it say about our society in South Africa? It hurts.”

Paw Prints on the Fault Line

Is it possible to pamper one’s Pomeranian at a plush local resort without feeling complicit in the city’s persistent chasms? Or do the defenders of the dog hotel industry have a point, viewing these businesses as much-needed economic engines, generative of jobs and even community uplift? Could the dog hotels, oddly enough, be one of the few spheres where economic mobility is—at least in a small way—being addressed? Or is this simply a well-furnished stage for the city’s age-old inequalities to play out, lapdogs on loungers up above and hungry children at street level?

What’s clear, as elaborated by NPR, is that Cape Town is a city where you can host a doggy wedding under hand-painted murals, stroll past a tent encampment on your way out, and be left pondering the invisible boundaries between comfort and survival, pet care and social care.

So: as tails wag atop sky decks and tents huddle under highway bridges, you have to wonder—who’s really in the doghouse here?