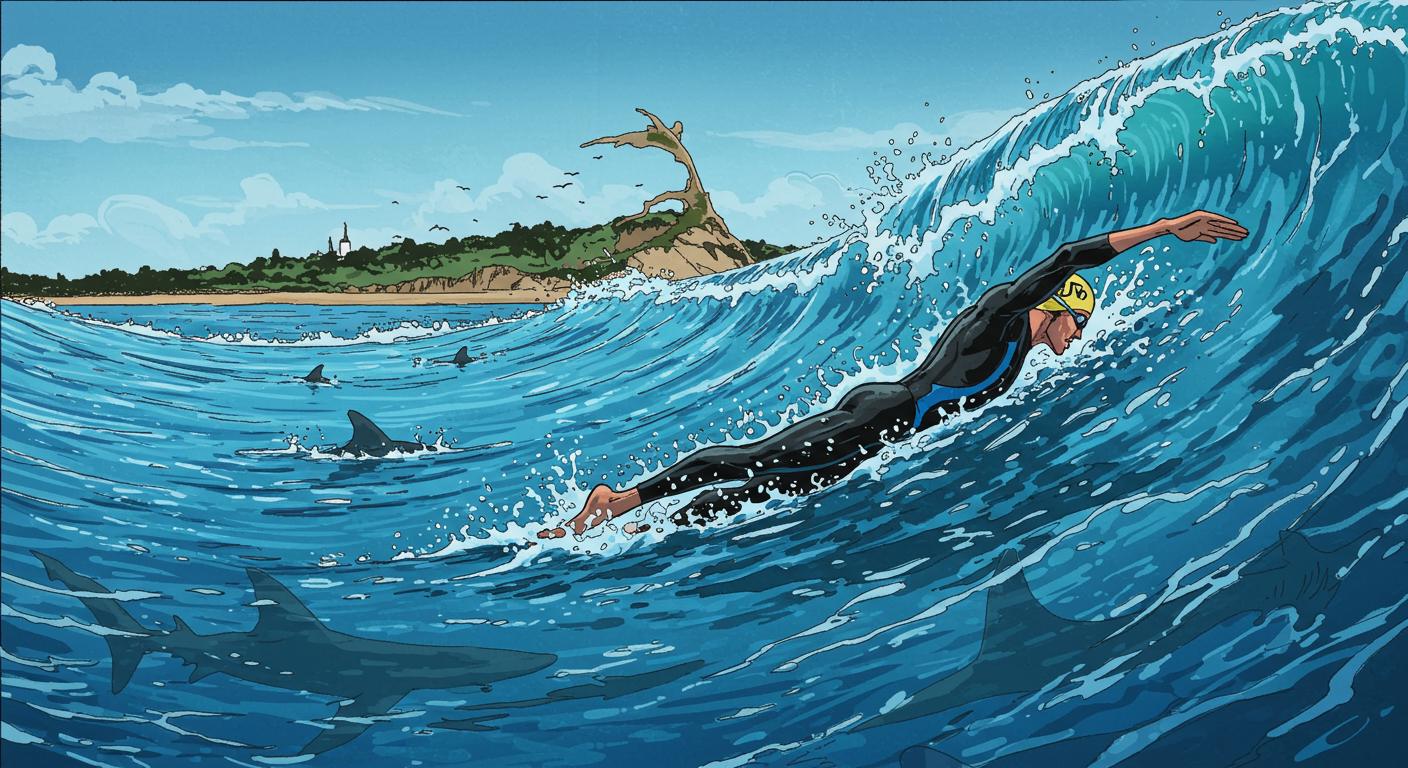

Some people celebrate a movie anniversary by rewatching the film or maybe eating themed cupcakes. Lewis Pugh, on the other hand, marked the 50th year since Jaws sent swimmers scurrying for shore by doing laps—approximately 59 miles worth—around Martha’s Vineyard. If the plot of Jaws gave you an enduring fear of dipping a toe in the ocean, this story may suggest a completely different take on who’s the real menace beneath the waves.

An Audacious Lap for the Maligned Shark

According to a recent report from UPI, Pugh—a British-South African endurance swimmer known for picking challenges that blur the line between impressive and improbable—spent nearly two weeks wrapping himself in cold water and anticipation around Martha’s Vineyard. This island, of course, owes its pop culture infamy to Spielberg’s cinematic shark. UPI cites Pugh’s own social media reflections on the ordeal, describing “cold water, relentless wind, big waves and the constant thought of what might be beneath me.” There’s a fitting symmetry: a swimmer voluntarily braves the birthplace of aquatic paranoia, not to escape sharks, but to throw them a lifeline in public perception.

Pugh intentionally chose Martha’s Vineyard on the 50th anniversary of Jaws, as highlighted in UPI’s report, aiming to counter decades of sharks being cast as villains. “For the past 50 years, it’s all been about fear and about the danger of sharks. What I want to do is I want to try to change the narrative for a new generation and say sharks actually bring life, they sustain life, they make oceans healthy,” as Pugh explained to PBS News, in comments relayed by UPI.

The Jaws Effect and Its Ripple

In a detail spotlighted by UPI, Pugh blamed the legacy of Jaws and its sequels for misleading entire generations about sharks’ true nature. “They portrayed sharks in a way that they are villains. They’re out to get humans and we know that they are nothing of the sort. And so this is an opportunity to try and tell a new narrative for a new generation,” he said, according to statements routed through UPI’s reporting on his PBS News interview.

It’s the kind of pattern that becomes familiar when trawling through the records of public fear—pop culture transforming rare statistical happenings into household terror. The reality, quietly documented in marine biology papers and seldom in summer headlines, is that shark attacks are staggeringly unlikely. Still, the visceral image endures, probably due to a combination of ominous cello music and good editing.

Is it inevitable that an animal whose role in the ecosystem is as crucial as it is misunderstood becomes a stand-in for pure anxiety? Pugh’s marathon aims to disrupt that feedback loop, one shoreline at a time.

Shifting Tides (and Narratives)

UPI’s article sums up a recurring human trait: our tendency to mythologize the unknown, especially when it allows us to keep a comfortable distance from the real story. Sharks, as oceanic “others,” get the narrative short straw—rarely celebrated for their role in balancing marine life, but often demonized as movie monsters. Can a single long-distance swim really challenge that collective narrative? Or are we, as a culture, just too comfortable under our metaphorical beach umbrellas to notice the ecosystem slipping away beneath the surface?

Pugh frames his swim—according to remarks captured in the UPI piece—as less of an epic for personal glory and more of an invitation to skepticism and curiosity. He’s not selling heroics so much as urging a second look at our long-held aquatic anxieties. It’s the same gentle nudge librarians and archivists have been giving for ages: don’t just accept the headline, examine the pattern behind it.

The Bizarre Normalcy of Going All In

If nothing else, a man swimming around the entire island that served as the original shark-boogeyman backdrop, just to shift the public image of sharks, is a very specific type of eccentric advocacy. One that feels stranger the longer you ponder it—and perhaps more admirable. Choosing to lobby for a misunderstood animal not with a fundraising gala, but with twelve straight days of exposure to bracing Atlantic conditions, suggests a conviction found more often in old newspaper clippings than modern-day stunts.

Does this mean the next generation will watch Jaws with more sympathy for the fish? Given the staying power of a good story, probably not immediately. But, as documented in UPI’s coverage, maybe Pugh’s efforts slot into a weirder, maybe wiser tradition: the one where people try rewriting fearsome legends from outside the spotlight, through thoroughly odd (and oddly hopeful) means.

Looking back, it’s almost comforting to realize that, in a world wired for viral anxieties and blockbuster fears, sometimes all it takes to start unraveling an old myth is a swim of improbable proportions. Is that approach likely to be replicated? Highly doubtful—though as anyone with a stack of obscure newspaper clippings knows, there’s never really a last word on human oddity, or on our willingness to swim against the current in service of a cause.