Some headlines demand a double take—and Russian lawmakers declaring a formal critique of Shrek is a prime example. On the scale of international concerns, one might expect the Kremlin to be more focused on sanctions or military hardware than the personal growth arcs of a green ogre. Yet as The Moscow Times reports, a recent State Duma roundtable was convened precisely to parse the threat posed by Western animated antiheroes, with Shrek as the unlikely leading villain.

Who Framed Shrek?

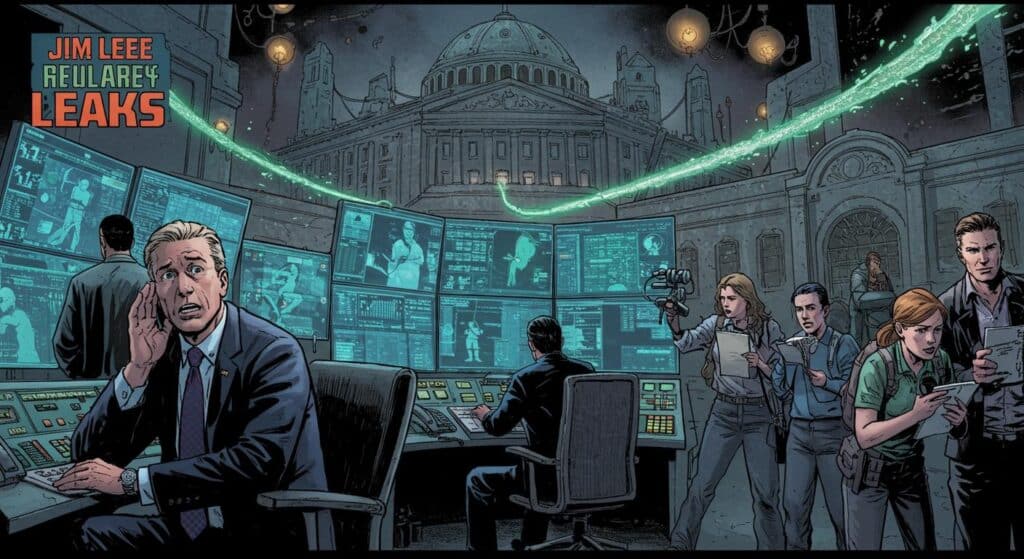

In a presentation that could charitably be described as unconventional, State Duma deputy Yana Lantratova aired slide comparisons between classic Soviet children’s films and toys (heroic, positive, physically flawless) and those “originating in Western countries”—with Shrek and the Grinch displayed front and center. According to visuals cited by The Moscow Times, one of Lantratova’s slides lamented: “Gradually, with the infiltration of Western culture, characters began to appear who embodied negative traits but were elevated to the status of positive characters. The image of the purely positive character began to fade.” A slide-show metaphorical fog descended, animated ogres and green mischief-makers in tow.

Described in the outlet’s reporting, Lantratova opined that while these characters “don’t seem bad, they have both physical and personality flaws.” Is it the questionable dental hygiene, the body positivity, or simply the suspicious number of onions? The specifics remain slippery, but the overall anxiety appears rooted in the encroachment of what she deems non-traditional values.

Swamp Things and Spiritual Values: Russia’s New Cultural Front

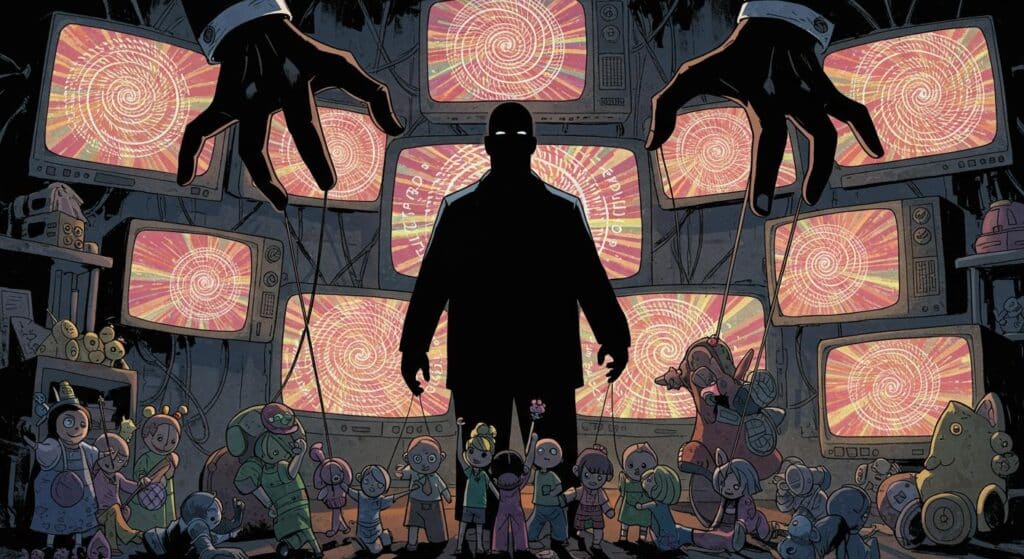

The roundtable’s broader mood was hardly one of lighthearted critique. Sergei Mironov, leading the minority party A Just Russia, characterized these imported cartoons as weapons in a “hybrid war,” warning that, as governments opposed to Moscow allegedly believe, “If you want to defeat the enemy, raise their children.” Echoed in The Moscow Times’ coverage, Mironov accused the West of “very actively” indoctrinating Russian children—not just through overt political messaging, but via bedtime animation.

It would be easy to laugh off the idea that Shrek is some arch-agent of Western subterfuge, but as noted in the Moscow Times article, Lantratova points to a “legal gray area” that she claims prevents Russian authorities from banning Western children’s content outright. She expressed her intention to relay these concerns and proposals to the parliamentary working group on preserving “traditional Russian spiritual values.”

One is left imagining whether legislative anxiety could soon see Shrek dolls swapped out for plush Cheburashkas in Moscow’s toy shops, or if this is more a demonstration of cultural gatekeeping than a real plan to sweep the swamps clean.

Between Onion Layers: What Does an Ogre Represent?

A nation’s mythmaking often says as much about its internal preoccupations as its external threats. Seeing the Duma devote energy to analyzing the flaws of CGI antiheroes might seem odd, but there’s a certain pattern-recognition at play: social upheavals and generational changes have long found their scapegoats in whatever media kids happen to be consuming.

In a detail highlighted by The Moscow Times, the driving anxiety among lawmakers is the potential loss of the “purely positive character”—those upright, unblemished figures often pushed in Soviet animation. It’s an interesting contrast: Soviet storytelling’s orderly optimism pitted against DreamWorks’ swamp logician, a reluctant hero with a chip on his shoulder and mud on his boots.

Is the ogre-as-bogeyman just a reflection of broader discomfort with modern complexities, where characters—and maybe citizens—are allowed to be messy and still be protagonists? If so, what does it reveal about the shifting boundaries between private taste and state-mandated virtue?

A Final Note from the Swamp

Every so often, the strangeness of contemporary life reveals itself best not in myths or legends, but in bureaucratic proceedings and televised roundtables. Russia’s parliamentary preoccupation with Shrek is a reminder that the dividing line between “serious” politics and the theater of the absurd is sometimes porous; that anxieties about influence and identity can crystallize even around cartoon antiheroes.

And as these debates unfold, somewhere out there a child (perhaps in Yekaterinburg, perhaps in Eugene, Oregon) is likely laughing at a fart joke delivered by an animated ogre, blissfully unaware of the cultural clash unfolding in government halls. In the end, maybe that’s the piece overlooked: no matter how many committees or culture war manifestos come and go, kids find their own lessons—sometimes from role models more complicated and green than any official canon would allow.