There are moments in American civic life so wonderfully baffling that you almost have to tip your hat. Robert F. Kennedy Jr.—once known mainly for his environmental activism and, more recently, for his passionate and controversial positions on vaccines—is now the nation’s Health Secretary. He’s all but synonymous with vaccine skepticism, has testified before Congress about the “leakiness” of the measles shot, and yet has managed to arrive at a rare patch of common ground with, well, just about everyone: don’t take medical advice from him.

When the Most Basic Question Becomes a Tightrope

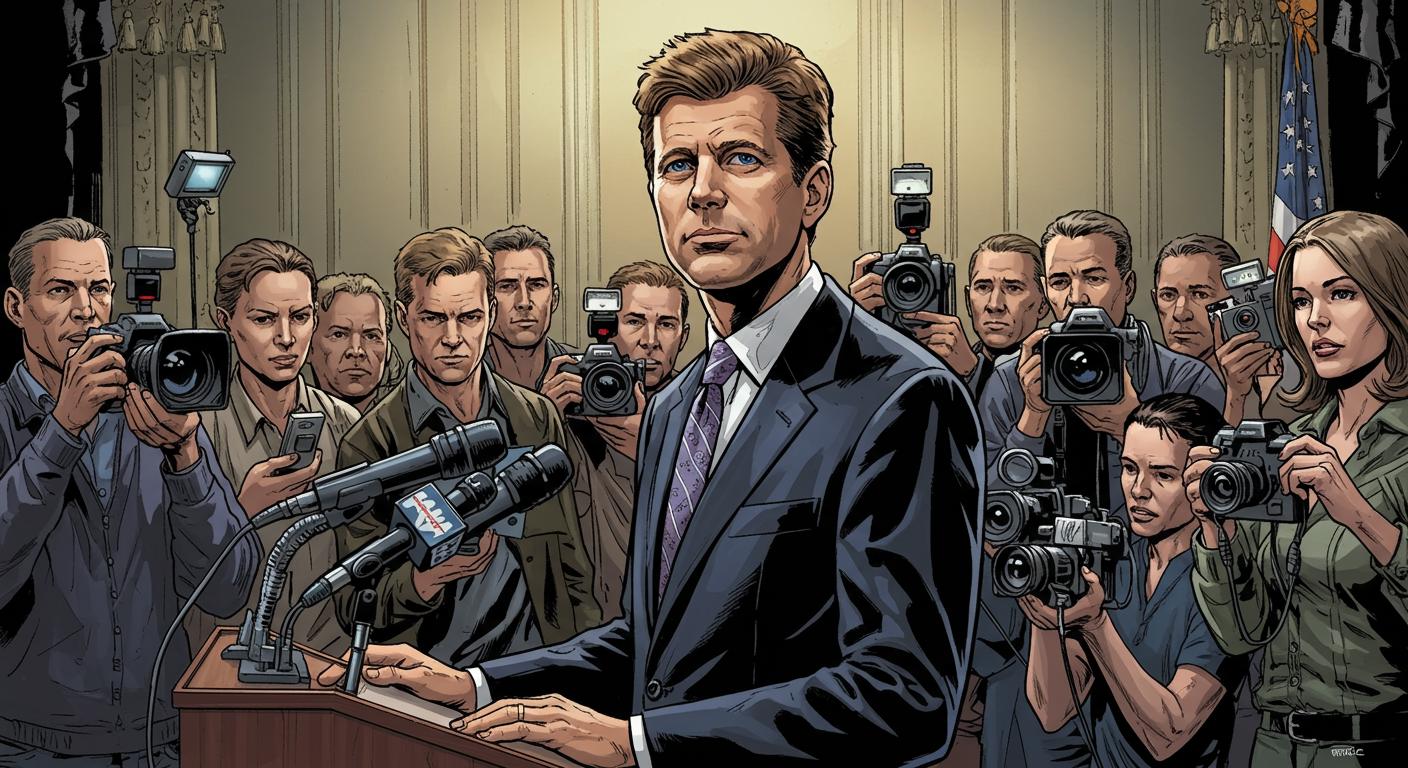

It’s unusual, watching the nation’s top health official artfully dodge questions that would seem, at first glance, to be central to his post. During a recent House committee hearing, described in USA TODAY, Rep. Mark Pocan asked Kennedy whether, were he the parent of a young child today, he would have that child vaccinated for measles. Kennedy’s first response: “Probably for measles.” It didn’t take long for him to step back from the precipice of commitment, though, clarifying that, in his words, his views on the subject are “irrelevant.”

He doubled down: “I don’t think people should be taking medical advice from me.” Pocan, not missing a beat, observed that providing guidance is a large part of the CDC’s remit. Kennedy, however, maintained his stance, explaining that his department’s goal is to lay out information on public health “accurately as we understand them, with replicable studies,” but declining to issue advice. When pressed further about polio and chickenpox vaccinations, Kennedy consistently kept to the refrain: he’s not in the business of personal recommendations.

For a man who’s built a public profile on skepticism of vaccines—and spent years questioning their safety and efficacy, as reported by USA TODAY—this sudden embrace of personal non-committal is quite an adjustment. It’s all the more striking given his more recent statements about “leaky” measles vaccines, a claim certainly at odds with the consensus among medical experts.

Private Decisions, Public Perception

Questions about Kennedy’s own record came up during his Senate confirmation as well. On that occasion, USA TODAY recounts, he gave a straightforward answer: “All of my kids are vaccinated.” In the ever-evolving saga of Kennedy’s relationship with vaccines, this detail seems to hover awkwardly over the more recent hedging, raising the question—if it’s good enough for the Health Secretary’s family, why the reluctance to affirm it for others?

Further adding to the patchwork of Kennedy’s public messaging, Rolling Stone reports on a recent social media escapade: Kennedy posted photos of himself swimming with his grandchildren in a creek known to be off-limits due to sewage contamination, according to National Park Service warnings. It seems his caution about personal advice in public fora doesn’t always extend to personal choices. Prioritizing hands-on risk assessment, perhaps?

Rolling Stone also documents Kennedy’s careful avoidance when asked about polio vaccination—a disease largely eradicated by exactly the intervention in question. Here too, he maintained his newfound policy of professional reticence, sidestepping the sort of direct endorsement (or criticism) one associates with the role of chief public health officer.

Procedural Wizardry and Perplexed Lawmakers

While Kennedy’s approach to public health communication might be artful, his approach to public health policy has left lawmakers more than a little frustrated. Funding decisions for agencies like the NIH and CDC have come under scrutiny, with Rolling Stone highlighting Rep. Rosa DeLauro’s concerns about cuts to vital research and staffing. The administration’s sometimes roundabout handling of congressional appropriations brought heated exchanges during the hearing, as DeLauro challenged Kennedy on his willingness to spend congressionally appropriated funds.

In these exchanges, Kennedy insisted that he would use whatever budget Congress assigned, but remained firmly noncommittal about the administration’s broader plans for funding and staffing. The magazine, earlier in its account, details DeLauro’s critiques of the administration’s ongoing “gutting” of America’s health protection agencies—a backdrop that transforms Kennedy’s cautious rhetoric at the witness table from mere personal quirk to a matter of tangible consequence.

The Advice Paradox

Stepping back, there’s an oddly refreshing quality to Kennedy’s candor: “I don’t think people should be taking medical advice from me.” For once, a political appointee is telling us to trust the experts, not the personality—which, in an era of social media medical influencers, isn’t the worst baseline.

And yet, when your title is Health Secretary, absolute neutrality can itself be a form of guidance. What does it mean when the country’s point person on public health policy tentatively advocates only for uncertainty? How does the average American interpret a message of “ask your doctor, not your Health Secretary”? Does this inspire confidence or just highlight our era’s particular flavor of bureaucratic irony?

One thing is clear: when even the Health Secretary suggests you look elsewhere for practical health advice, perhaps we’re all overdue for a reminder on where, exactly, we’re getting our information. If nothing else, Kennedy’s hands-off approach is a strange kind of transparency—one that, for now, unites skeptics and supporters in a single, quietly bewildered nod.