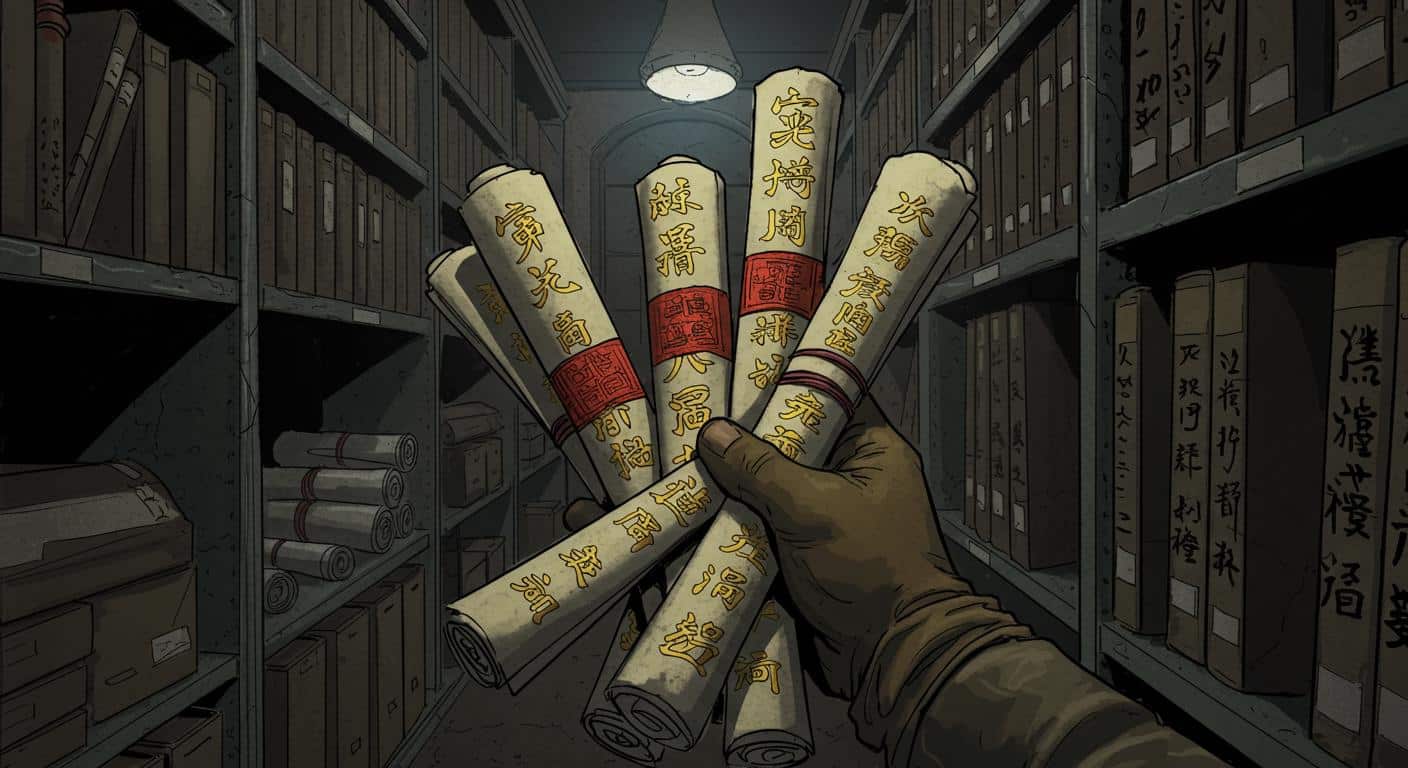

If you ever wondered who, exactly, those library warning signs about “serious consequences for theft or vandalism” are for, wonder no more. As reported by NewsNation, federal authorities allege that one man with a pocketful of aliases quietly made off with more than $200,000 in rare Chinese manuscripts from UCLA’s library—some dating back to the time of Kublai Khan. That’s not scanning overdue copies of “The Catcher in the Rye”; that’s literal theft of the written record.

The Curious Case of the Disappearing Manuscripts

Federal prosecutors, in details provided by NewsNation, allege Jeffrey Ying (age 38, Bay Area resident, collector of alter egos) orchestrated this paper heist between December 2024 and July 2025. Under names like Jason Wang, Alan Fujimori, and Austin Cheng, Ying reportedly exploited UCLA’s relatively new system, as described in NewsNation’s coverage, where prospective users could obtain library cards and check out materials without presenting official ID. For anyone who’s ever gotten a little twitchy signing out microfilm at a university library, the absence of an ID check here feels…bold.

The missing items? NewsNation relays these were unique and historic manuscripts from the 1200s, and not items available for casual browsing—UCLA restricts access to such treasures, requiring reservations for handling. According to NewsNation (citing information from a U.S. Department of Justice release and the Los Angeles Times), Ying would sign out valuable manuscripts in groups, then substitute “dummy books”—either inexpensive Chinese manuscripts or blank volumes dressed up with computer-printed faux labels designed to mimic the real thing. Sometimes, he even went so far as to print out fake barcodes and tags, attempting to clone the originals.

When High Security Meets Low Standards

NewsNation highlights an intriguing gap in security: while UCLA’s policies required staff to be present in the reading room with special collections, there was reportedly no equally robust process for vetting items returned to the library for authenticity. No policy required staff to authenticate a returned 700-year-old manuscript versus a cleverly disguised decoy. The report suggests that these fakes could rejoin the shelves unnoticed—a troubling oversight, especially given the stakes.

It invites the question: did anyone ever pause, holding a suspiciously pristine “antique,” and think “that’s odd”? Or were the forgeries simply accepted with minimal scrutiny, blending in among priceless originals?

The Aliases, The Getaway, The Underwhelming ID

NewsNation, referencing both federal officials and surveillance footage, explains that investigators eventually matched Ying’s IDs and stolen library cards—issued under a roster of aliases—to a single individual. The pattern became clear: six manuscripts checked out as Jason Wang, eight more under Austin Chen, and reportedly even similar operations at UC Berkeley tied to the Alan Fujimori identity.

Investigators tracked Ying’s travel patterns as well, with NewsNation documenting that he routinely left for China within days of each theft—a fact that led officials to suspect the manuscripts were being shipped abroad for sale, or at least hidden far from U.S. authorities. On August 6, Ying was arrested while attempting to leave for China. At that time, federal prosecutors say, he was found with a fake California ID (in the name of Austin Chen) and two library cards under his known aliases in his Brentwood hotel room.

At present, NewsNation states that Ying stands charged with theft of major artwork—a crime carrying a potential sentence of up to 10 years in prison. He remains in custody due to being considered a flight risk.

Medieval Books and Modern Mistakes

Despite the investigation, NewsNation reports that at least ten manuscripts—some valued as high as $70,000—remain missing, and it does not appear that authorities have yet recovered them. The cultural value, as underlined by UCLA officials speaking to the press, is as significant as the monetary loss. The whole scheme unraveled after the head of UCLA’s East Asian Library noticed certain items missing and spotted “dummy books” substituted in their place, a detail relayed in NewsNation’s summary of the broader probe.

In reflecting on this quiet library caper, the central question lingers: can institutions committed to open scholarly inquiry ever fully secure their rarest treasures from a determined and resourceful thief? Or is some risk inherent when you trust strangers with the memory of centuries past?

History is full of tales about lost books and vanished manuscripts—some resurfacing generations later in dusty collections or auction catalogs. Perhaps, in time, a curious bibliophile will encounter a 13th-century Chinese manuscript looking suspiciously well-preserved and wonder, “Shouldn’t that be at UCLA?” Until then, the gaps on the shelves tell their own quiet story.