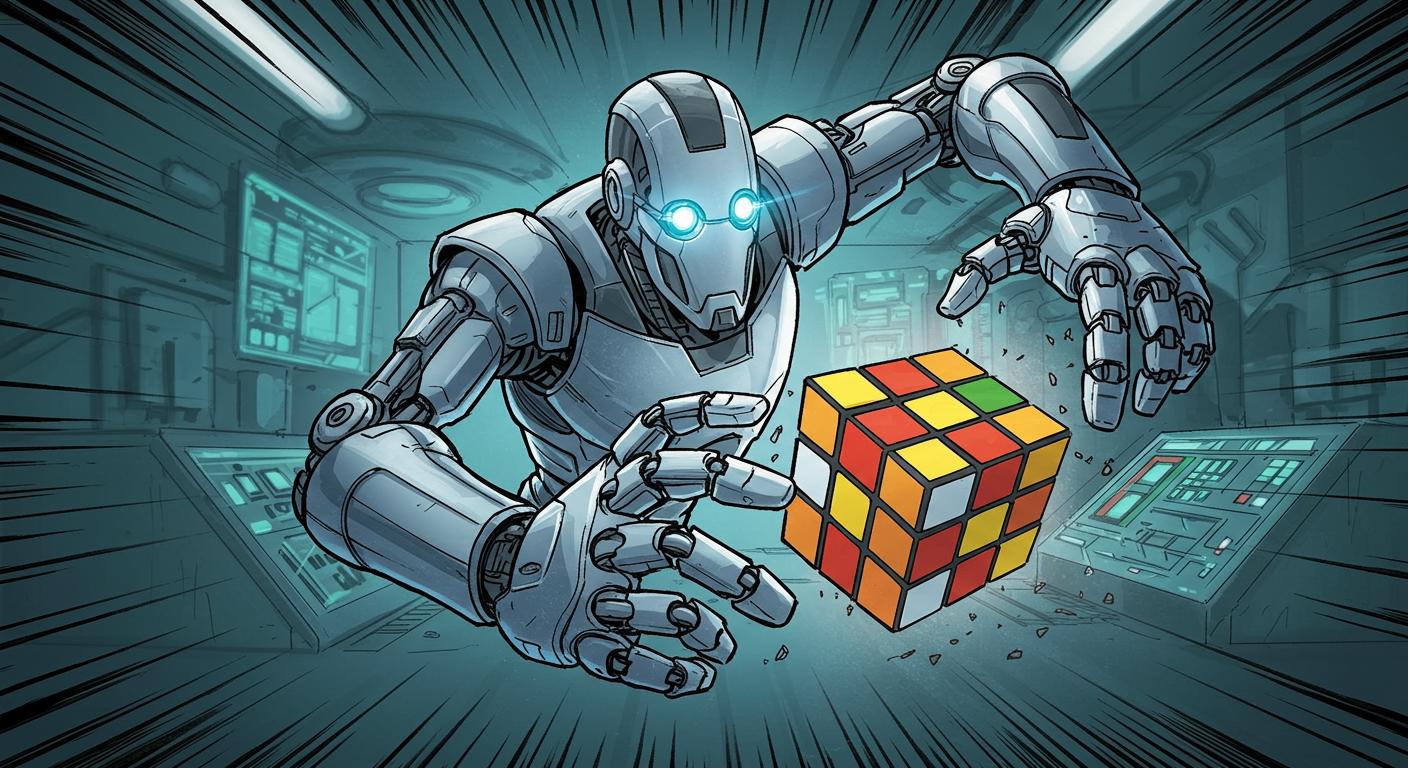

There are moments when the universe, perhaps just for its own entertainment, finds a way to make human benchmarks suddenly seem quaint. Case in point: as reported by UPI, a quartet of engineering students at Purdue University have constructed a robot that can solve a standard Rubik’s Cube in an astonishing 0.103 seconds. That’s not slick marketing copy—Matthew Patrohay, one of the students, points out that “a human blink takes about 200 to 300 milliseconds,” meaning this robot’s work is finished before your eyelid comes anywhere near halfway shut.

The Art of an Unseeable Solution

UPI details that this mechanical savant—christened “Purdubik’s Cube” by its creators Matthew Patrohay, Junpei Ota, Aden Hurd, and Alex Berta—emerged from a co-op program at Purdue’s Elmore Family School of Electrical and Computer Engineering in West Lafayette, Indiana. With the exacting tone you’d expect of engineers, Patrohay declared simply, “We solve in 103 milliseconds.” For reference, the previous Guinness World Record belonged to a robot built by Mitsubishi Electric Corporation in 2024, which managed a time of 0.305 seconds. In just one year, the record has been clipped by two-thirds—if only my unread email folder would shrink at a similar pace.

As UPI notes, the robot’s feat is less a feat of showmanship and more a technical flex: before you can even register the blur of motion, the cube is restored to its precise rainbow uniformity. It’s one of those achievements that reads almost like a punchline—solving a complex puzzle in the time it takes most people’s neurons to fire off a “wait, what?”

The Strange Comfort of Losing to Robots

It’s not exactly a crisis that a machine now outpaces our reflexes in recreational puzzle-solving. Yet, as documented by UPI, this little corner of engineering bravado quietly steals away another human crown—speedcubers of the world might need to find solace elsewhere. There’s a certain detached amusement to knowing robots have toppled yet another odd frontier, and a bigger amusement still in imagining how seriously teams take these microseconds shaved off their creations’ times.

But does this mean that future record attempts will be measured in increments so small only a high-speed camera (and perhaps a Guinness adjudicator with a stopwatch and a strong mug of coffee) can keep up? And how do we even process an achievement we can’t see, can barely comprehend, and certainly can’t replicate without a backpack full of servo motors and a group project?

Oddities, Blinks, and the Delight of Peculiar Progress

UPI positions this record squarely among the magazine rack of the bizarre: just a few brows over from a duck triggering a Swiss speed camera (down to the anniversary, no less) and a circus performer breaking records by dangling from her hair for over 25 minutes. What’s strangely comforting is that—machine or human—a good world record is rarely about utility and almost always about the thrill of the utterly unnecessary.

So, will next year’s contender solve a cube seemingly before humans even finish scrambling it? If the unspoken race between nervous system speed and servo motor precision continues, we may need to put the Guinness records under quantum review.

For now, machines can keep the Rubik’s Cube crown. The rest of us can blink, marvel, and maybe take comfort in the fact that not every contest is meant to be winnable by humans—or even visible to the naked eye. Sometimes, being thoroughly outpaced is the most satisfying footnote of all.