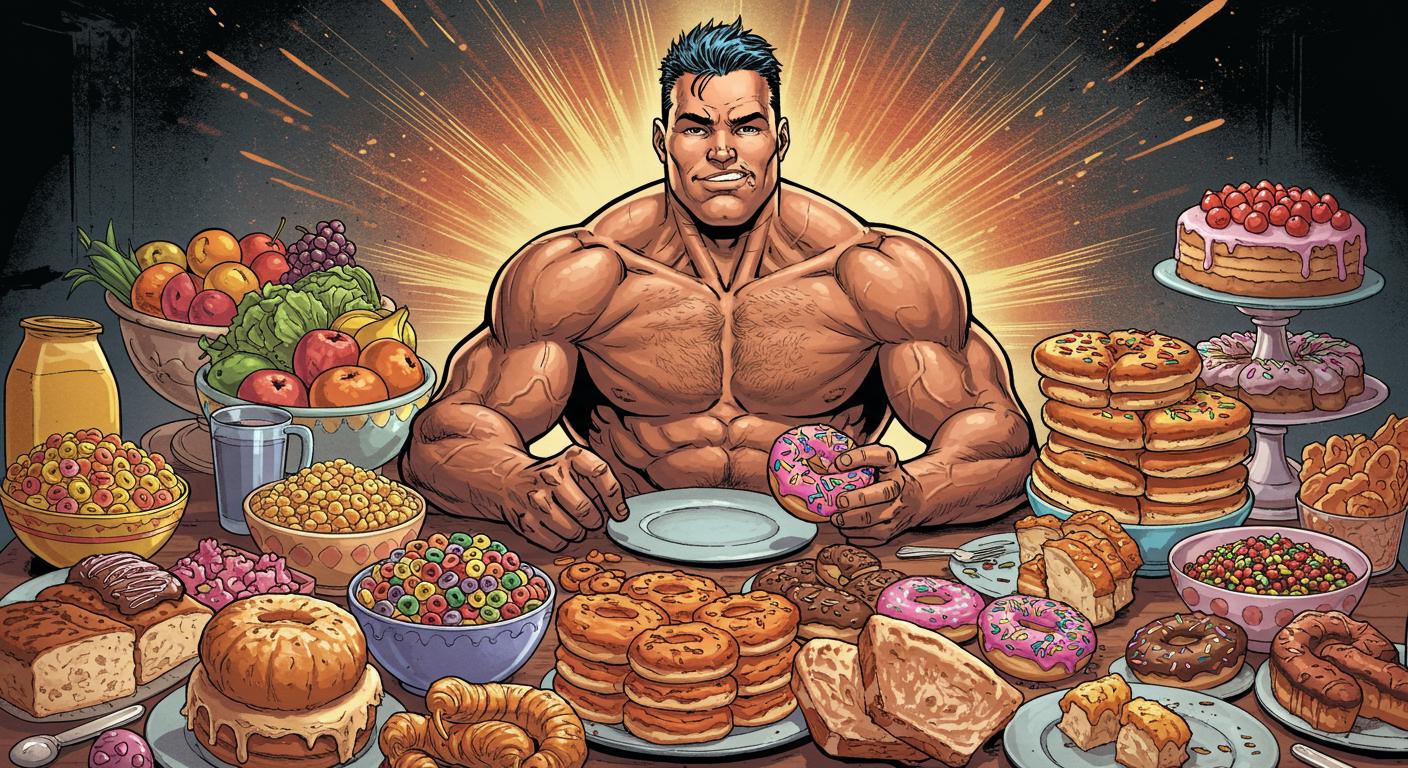

Every so often, a story lands squarely in the “wait, seriously?” category. Thomas Sheridan’s singular relationship with food more than qualifies, floating somewhere between astonishing and quietly surreal. Recent reports, including coverage from both the New York Post and Oddity Central, highlight Sheridan’s diet that appears to have bypassed the produce aisle altogether.

The Art of Living on Toast

At 35, Sheridan, who resides in Liverpool, survives on a routine that few dieticians would endorse: two loaves of white bread daily, three bowls of Shreddies cereal, and a rotation of Haribo and Hula Hoops rounding out his limited menu. According to accounts featured in the New York Post, his aversion is so profound that the idea of even attempting an egg and sausage sandwich is enough to send him running for the exits (sometimes literally, given his description of a long-range egg-induced vomit incident).

But this isn’t a stubborn case of selective childhood eating carried into adulthood. As Oddity Central details, Sheridan spent years being told to “just starve it out” or try bribery—methods that predictably fell flat. He was finally diagnosed at age 33 with Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID), a condition recognized by the British Dietetic Association in 2013 and only recently classified by the World Health Organization in its International Classification of Diseases, as both sources confirm.

Sheridan himself describes the experience as “torture” and laments the impossibility of joining in on ordinary meals. The Post further explores the lengths to which his family went, including arranging for him to skip school lunches in favor of a predictable home-cooked round of toast. Despite attempts at therapy, the inconsistencies in available treatment—often resulting in a different provider every session—left him without much hope of gradual change.

Social Isolation and the Beige Plateau

Described in both Oddity Central and the Post, Sheridan’s world has, by necessity, shrunk to fit the limitations of his dietary needs. Everyday socializing often revolves around meals—something he finds nearly impossible. The outlets detail his physical struggles as much as the social: attempts at employment resulted in dangerously rapid weight loss. To compensate for his nutrient-poor regime, he now relies on supplements such as protein powders and vitamins, though he specifies only certain flavors are tolerable—a testament to how strongly ingrained his sensory restrictions have become.

Further highlighted by the New York Post, economic pressures add another layer—he relies on specific brands, and even the cost of staples like Weetabix can become a real obstacle. There’s little in his experience to suggest this is driven by preference or even intentional resistance; more, it’s an all-encompassing wall his brain refuses to scale.

Friends wonder about the culinary monotony, but as Sheridan states, he’s come to accept this very limited menu. The notion of ever sitting down to a bowl of stew with his family remains, for now, a distant dream—one he hopes to address through fundraising for private hypnotherapy, as Oddity Central notes.

Oddities and Everyday Realities

It’s almost impossible not to marvel—if a bit uneasily—at a person who’s never eaten so much as a carrot stick, a scrap of fruit, or a slice of ham. Yet, beneath the curiosity, what emerges is a rather poignant question: how many everyday social rituals hinge on something as simple as sharing a meal? Earlier in the Post’s report, the difficulties Sheridan faces in work, friendship, and participation in ordinary gatherings all begin with his system’s revolt at non-beige food.

Unlike more commonly recognized eating disorders, ARFID isn’t tied to body image or calorie-counting, but manifests as something closer to a reflexive block, invisible but deeply isolating. Oddity Central underscores how recently this disorder has entered mainstream awareness and how Sheridan himself has never met another individual with the same diagnosis, despite its official recognition.

Room at the Table for Oddity

It would be easy—and not entirely unfair—to find some quiet amusement in a story centered around an exclusive devotion to bread, cereal, and the occasional childhood sweet. But the reality, as illustrated in these reports, is far less comic. Sheridan’s predicament raises questions about invisible barriers and the surprising complexity that can underlie life’s simplest routines. Perhaps, then, a touch of empathy is appropriate alongside the fascination. Has anyone among us not found themselves, at least once, just a little lost at the world’s table?

For Thomas Sheridan, fruits and vegetables aren’t optional so much as a fable—one day, perhaps, the story will have a more flavorful sequel. Until then, bread remains both the beginning and the end of the menu.