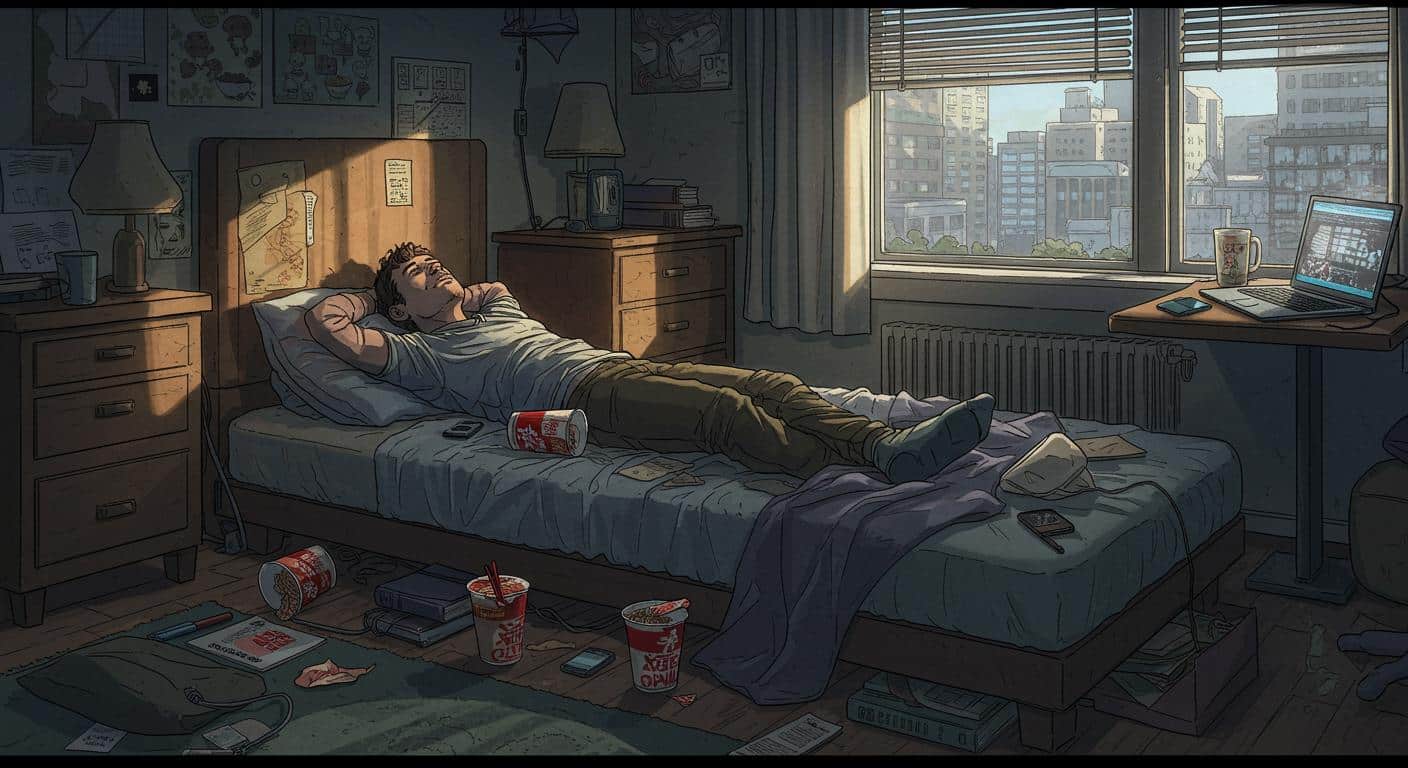

There’s a certain subversive logic at play when opting out of the rat race means literally living like a rat. In a reflection of both resignation and dry humor, unemployed Gen Z in China have started calling themselves “rat people” and, according to Fortune, are spending entire days nestled in their bedrooms, rarely showering or venturing outside. This self-imposed hibernation isn’t just a lazy habit—it’s being framed as a sort of passive protest against the relentless pressure of modern life and the seemingly out-of-reach employment prospects facing young adults.

Doona Dens and Digital Dissent

As documented by Fortune, many Chinese Gen Zers have stopped chasing jobs, instead embracing what’s described as a “bed rot” lifestyle: endless hours under the covers, phone in hand, offline in spirit if not in connectivity. The term “rat people” is worn as a badge of self-aware irony—a conscious choice to retreat beneath the surface rather than endlessly scramble in a race with no finish line. This movement recalls earlier youth-led trends like “lying flat,” but with even less pretense of eventual reentry into the hustle.

The article points out that this phenomenon is hardly contained within one city or socioeconomic bracket. Instead, it’s catching on as a kind of meme across China, and its themes—eschewing hustle culture, forming community through resignation rather than ambition—mirror the “bed rotting” trends visible among young adults in other countries. Given the context offered by Fortune, it seems what once would’ve been coded as apathy now broadcasts itself as a knowing, almost rebellious withdrawal.

From Burnout to Burrowing In

Fortune describes the current era as one where jobs can feel frustratingly unreachable for much of Gen Z, with economic uncertainty feeding a sense of futility. It’s not so much about laziness as it is about a pragmatic assessment of diminishing returns: why expend the effort when the rewards barely cover rent? Rather than framing this retreat as outright defeat, many young people are leaning into the narrative—not just “giving up,” but actively participating in a kind of anti-grind solidarity, all from the comfort of their beds.

This mass inclination towards hibernation does raise some questions. If a growing cohort openly identifies with rodents for their ability to hide from an overwhelming world, does that signify a breakdown in the social contract—or simply a recalibration of what’s necessary for sanity? The shifting tone, as Fortune outlines, hints at a worldview shaped as much by economic reality as by a desire for control over one’s own time, however unproductive that time may be.

While the image of unwashed, pajama-clad digital hermits may seem bleak, it’s also a quietly subversive response to pressure—and one that doesn’t pretend to have easy answers. Is this self-imposed isolation a meaningful act of protest, or just a global case of “if you can’t join them, nap instead”? Either way, the “rat people” seem content to stay burrowed until (or unless) conditions above ground improve. You have to wonder: is this the world’s gentlest revolution, or simply a logical response to a world that feels increasingly unwinnable?