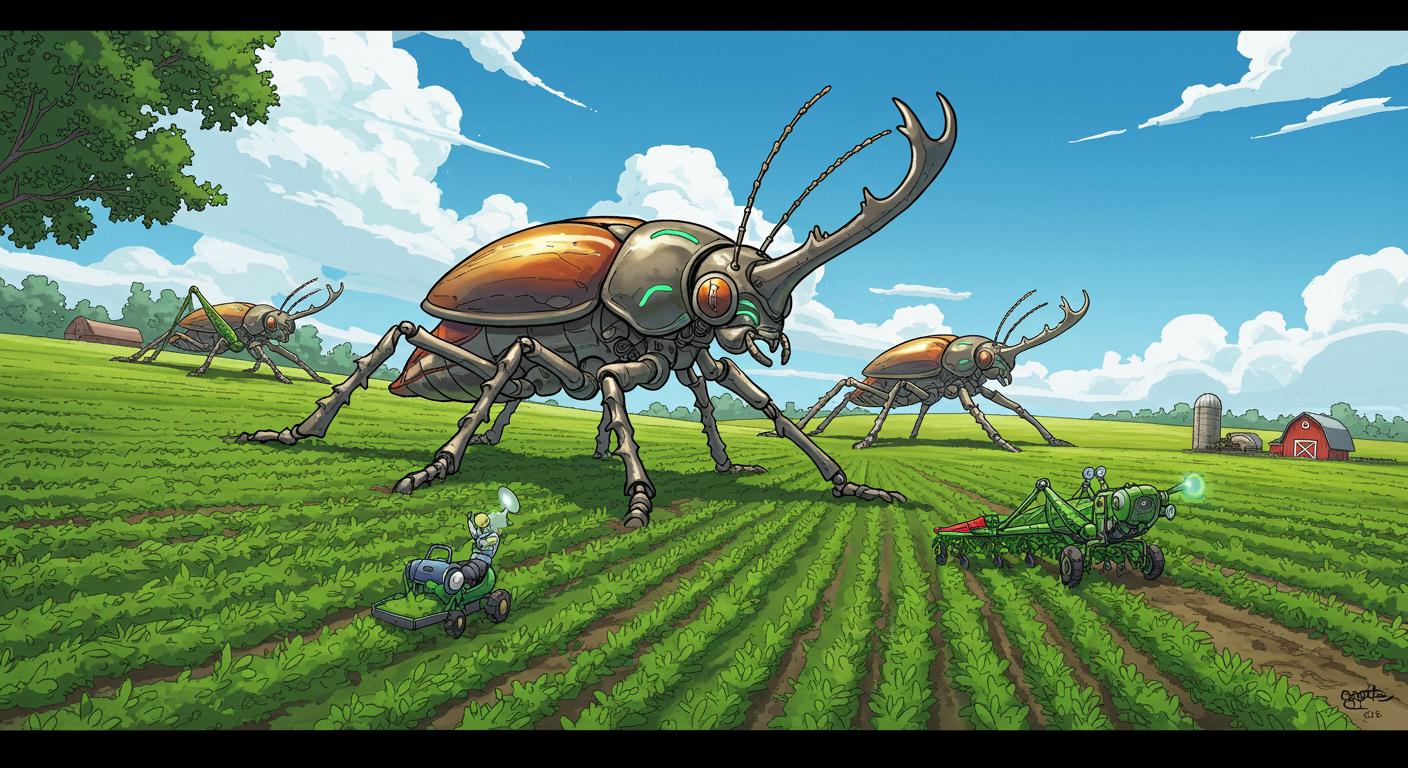

Nothing says “modern agriculture” quite like the sight of a giant, many-legged robot insect undulating its way beneath a bush of blueberries. Readers of a certain disposition might feel that childhood nightmares have finally found sponsors in the food technology sector, but in reality, we may be on the cusp of a weeding revolution. As reported by IEEE Spectrum, Ground Control Robotics is field-testing colossal centipede-inspired robots with a straightforward mission: hunt down weeds, spare the soil, and, perhaps inadvertently, spark a few sci-fi flashbacks among onlookers.

The Rise of the Robophysical Arthropod

Bioinspired robotics isn’t new, but the practical leap to actual farm work feels novel—especially when the robots in question borrow their strategy from centipedes rather than drones or tractors. As described in details provided by IEEE Spectrum, Dan Goldman’s team at Ground Control Robotics set out to design what Goldman dubs “robophysical” models: machines built not just to emulate, but to rigorously test the rules of animal movement in messy, real-world terrain. Goldman explains that these modular, cable-actuated robots emerged from academic study but, after enough field observations and trials, showed promise as actual laborers in the dirt.

Goldman and his colleagues found that once they tuned the robot’s mechanics—moving actuation away from the centerline and making it “unidirectionally compliant”—the machine could “swim” through particularly gnarly environments with minimal computation required. According to the outlet, this implementation lets the robots navigate tangled, uneven ground in places where other forms of automation often fail. That detail comes into focus when noting the sort of terrain perennial crops prefer: think wine grapes on rocky hillsides or blueberry bushes in overgrown patches. Not exactly rolling Kansas wheat fields.

A subversively practical rationale drives the design, too. GCR’s robots don’t just exist to flex their mechanical prowess—they’re aimed squarely at the difficult, expensive problem of weed control around sprawling or vine-like plants. Estimates cited by the publication put the price tag at more than $300 per acre for blueberries in California, and strawberries can top $1,000 per acre. Spotting and yanking weeds from such inhospitable terrain is an increasingly thankless job, complicated by the shrinking pool of willing workers. So, if you’re picturing these machines as the last resort before resorting to chemical sprays, you’re not far off.

Why Not Just Use Wheels (Or, For That Matter, a Goat)?

Addressing the skepticism that seems inevitable with any unusual robot design, Goldman points out that more standard agricultural bots—wheeled or quadrupedal—run into serious trouble on cluttered or unpredictable ground. As outlined by the IEEE Spectrum analysis, robots big enough to brute-force their way through would likely damage plants, while small, delicate contraptions become an exercise in frustration when the terrain fights back. With obstacles roughly the same size as the robots themselves, traditional control mechanisms struggle.

The team’s solution: more legs. By simply increasing the number of limbs, the robots can traverse underbrush and clamber over obstacles with surprising reliability—no vast sensor networks or algorithmic wizardry required. Goldman relates that, with this approach, the need for sophisticated “brains” all but disappears, replaced by a kind of mechanical intelligence hardwired into the robot’s frame. Notably, the affordable, repeated leg modules also keep costs reasonable, with projections indicating that GCR’s centipedes could ultimately sell for just a few thousand dollars each.

The report notes GCR is currently putting prototypes to the test with a blueberry farmer and a vineyard owner in Georgia, tuning mobility and sensor packages outside the carefully controlled world of laboratory floors. There’s also the prospect—raised both by the company and echoed in the article—that these mechanisms might one day show up in disaster response settings or, with design tweaks, even in military applications. (Because nothing says “multifunctional” quite like a robot that can both weed your carrots and crawl through rubble.)

Swarming the Fields…But For Good

The vision, as made clear in IEEE Spectrum’s piece and by GCR itself, involves not just one robotic bug, but swarms. Decentralized teams of centipede bots could theoretically roam fields day and night, starting with scouting tasks—monitoring plant health, mapping weeds—and eventually, when their formidable jaws (or perhaps lasers) are ready, physically removing weeds with considerably less collateral damage than heavy machinery or herbicides.

In a detail highlighted during the outlet’s reporting, the choice to rely on mechanical rather than computational intelligence allows for downward pressure on cost and complexity, supporting the notion that these swarms won’t be limited to showcase farms with massive budgets. It’s an example of robotics transitioning directly from academic novelty into the rough-and-tumble world, where only the most robust—and least fussy—innovations have a shot at longevity.

Crawling Forward

There’s an odd comfort in realizing that the march of robot insects isn’t about spectacle but about solving a labor conundrum that’s been festering for years. Will the sight of robotic centipedes pulling weeds at midnight make anyone’s glass of Pinot Noir taste better? Doubtful. But if these mechanical arthropods can ease the backbreaking, repetitive work for humans—and reduce the chemical load in fields while they’re at it—there’s a practical justification that transcends novelty.

Perhaps the most intriguing question is how quickly such machines will move from specialized, high-tech curiosity to routine fixture on the modern farm. Will the robot centipede someday join tractors and irrigation pipes as beloved—and possibly begrudged—farm implements? And, given their modularity and swarm potential, what unexpected roles could they crawl into next? At the very least, it’s safe to say that between cauliflower and caterpillar, agriculture’s future now includes a healthy dose of the peculiar.