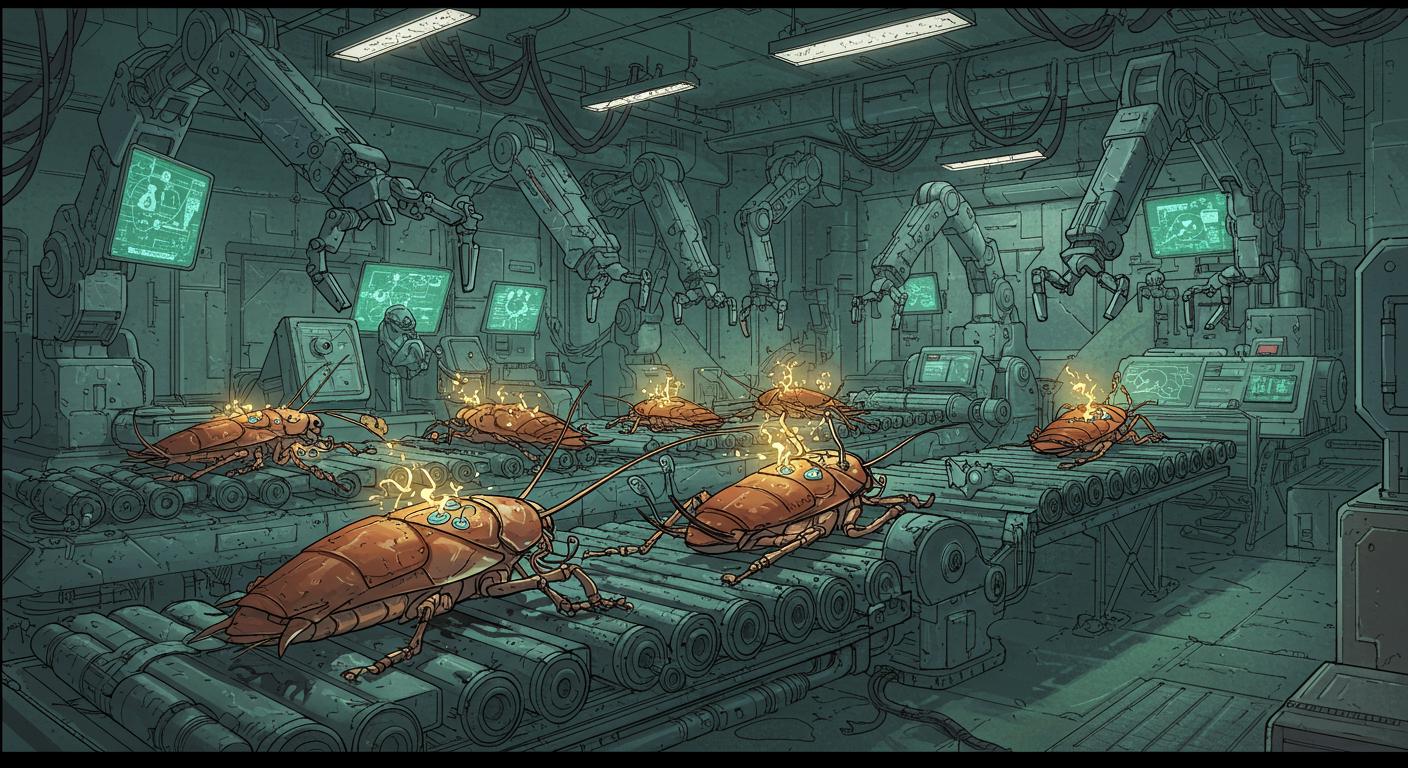

There are few technological developments quite as equal parts science fiction and mild existential unease as the “cyborg cockroach assembly line.” Yet here we are: researchers at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore have, as detailed in New Atlas, taken remote-controlled insect hybrids out of slow-motion mad science and into slick, production-line reality. The result? Cyborg cockroaches, ready to scuttle at your command, in just 68 seconds.

From Cockroach to Cyborg in About the Time It Takes to Brew a Coffee

The operation, masterminded by Professor Hirotaka Sato’s team, is more high-tech clinic than Frankenstein’s laboratory. According to the outlet, the system relies on a combination of anesthetized Madagascar hissing cockroaches, a UR3e robotic arm equipped with a nimble Hand-E gripper, and an Intel RealSense depth camera to ensure precision. The insect is secured on a platform, shifted into perfect position by a motorized rig, then measured for body length and width by the computer vision system. A segment of the back is exposed—a membrane between the pronotum and mesothorax, to be exact—so that two tiny electrodes, connected to a featherweight 2.3-gram “backpack,” can be embedded for remote stimulation. The robotic process then gently affixes the pack to the insect, and out slides a new member of the robo-roach workforce.

As explained in the report, this assembly-line transformation is a stark contrast to the laborious handcrafting approach, which previously took anywhere from 15 minutes to an hour. Earlier in the article, it’s also mentioned that both machine- and hand-modified roaches performed equally well in follow-up navigational tasks—think S-shaped path following and debris exploration.

Purpose-Built Peculiarity

Of course, mass-producing cyborg insects might sound like a plot point from a vintage pulp novel unless you know why. New Atlas chronicles that the intended use is far from frivolous: these bug-bots have already been field-tested in Myanmar following a magnitude 7.7 earthquake, where they ventured into the rubble in pursuit of survivors. Outfitted with cameras and transmitters, swarms of these critters could search for humans in places too tight or dangerous for human rescuers or even traditional rescue robots.

The outlet documents how the technology’s design goes a bit easier on its biological hosts (and their wearable gadgets) than earlier efforts—the electronic control unit requires just 40% of the electrical stimulation time and 75% of the voltage compared to similar systems. Notably, the backpacks are also removable, so the insects can be “demobilized” between missions. Whether or not they appreciate the break is an open question; perhaps a future study will ask the roaches for their customer satisfaction ratings.

From the Lab to the Field—at Scale

What really nudges this research out of quirky territory and into the annals of technological milestone is scale. As Professor Sato highlights, “By automating the process, we can produce insect-hybrid robots rapidly and consistently. It will allow us to prepare them in large numbers, which will be critical in time-sensitive operations such as post-disaster search and rescue.” Within this framework, the vision is of hundreds—perhaps thousands—of cyborg insects, each with a wireless communication-enabled pack, mapping out disaster zones, sharing data, and rerouting in real time to avoid overlap.

The article further notes that having swarms of these agents acting semi-autonomously could make all the logistical difference when seconds count. And, for those wondering if this is a permanent situation for the cockroaches, it’s clarified that the electronic backpack can indeed be removed.

Philosophical Ponderings from the Bug Production Line

Naturally, not everyone finds the idea of releasing swarms of electronically augmented insects into collapsed buildings comforting—or even terribly practical. In commentary highlighted by New Atlas, some readers voiced skepticism: Is this really superior to conventional search tools? Others mused about more creative uses, like emergency medication or food delivery in hard-to-reach spots, while a classic Jurassic Park refrain—“your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should”—makes its inevitable appearance.

There’s merit to these questions. Humanity has employed animals in rescue and warfare for centuries, but there’s a certain postmodern irony in deploying bugs by the hundreds, recharging their batteries, and sending them off for shift work in disaster relief. Is this one step closer to welcoming our insectoid overlords, or just a clever, albeit faintly unsettling, problem-solving tool?

Closing Observations from the Assembly Floor

In the end, maybe the most fascinating facet is how seamlessly these lines between living creature and machine are now not just being crossed, but mechanized and optimized for speed. Watching technology and biological life converge—one scuttle, one electrode, and one featherweight backpack at a time—raises questions even faster than these assembly lines can operate.

Will cyborg insects be a mainstay of humane, high-efficiency disaster relief, or simply a new twist in our long history of repurposing nature for human ends? As always, the answer is more complicated—and more fascinating—than a headline alone would suggest. But one thing’s for sure: if the future is going to be swarming with anything, it might just be insects with Wi-Fi.