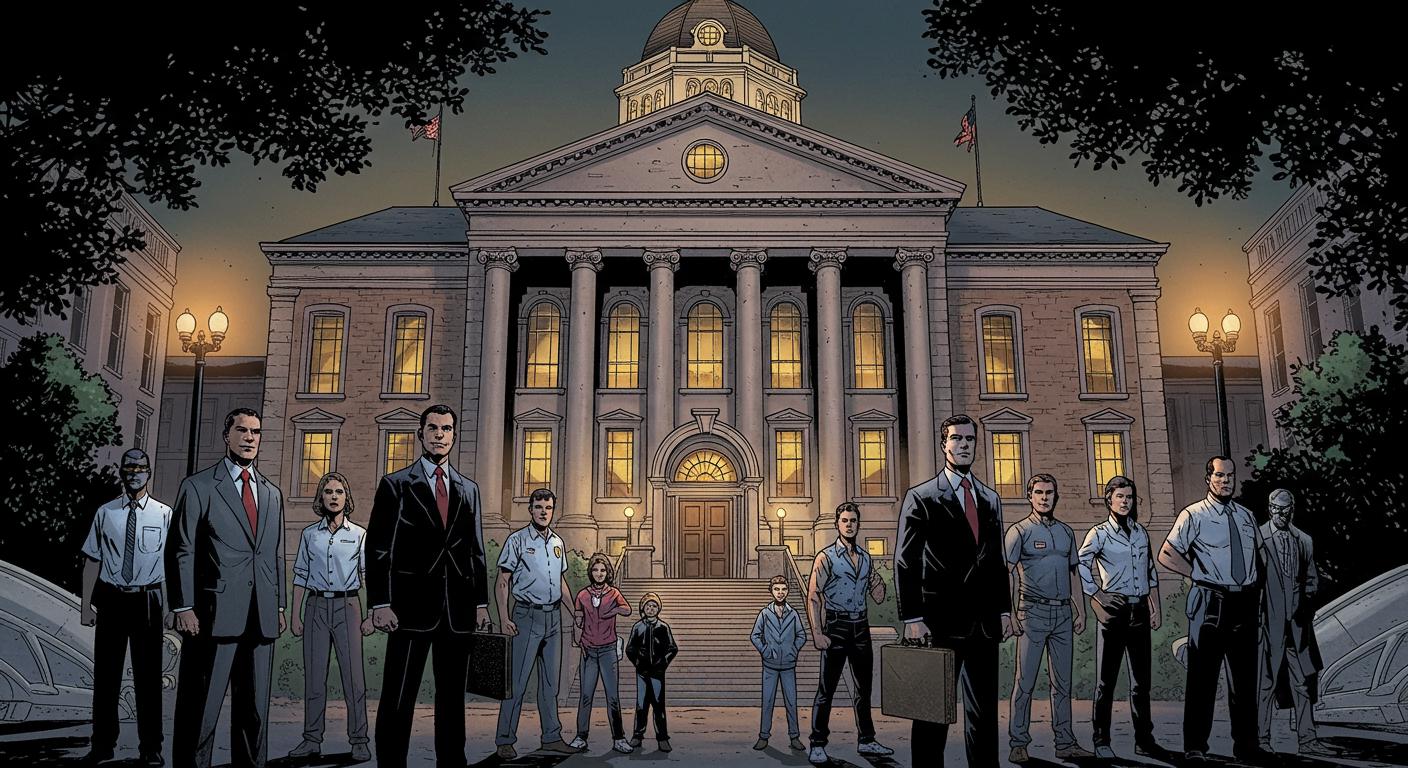

If you’re assembling a greatest-hits collection of peculiar modern culture clashes, the recent saga at The Samuels Public Library in Front Royal, Virginia, surely earns a place on the playlist. According to Lit Hub’s detailed account, this library—founded in 1799, before the ink on the Constitution was even dry—managed to outmaneuver an attempted takeover by a private equity-owned company. Why would private investors set their sights on a place where the most contentious thing is usually whether the new mystery novels get shelved before the next book club meeting? The answer, predictably, features both culture war theatrics and an enthusiasm for “efficiency.”

From Book Bans to Buyouts

The trouble began innocuously enough: as chronicled in Lit Hub, the library became the target of a group called “Clean Up Samuels,” who filed a barrage of complaints—hundreds, with a striking focus on children’s books with LGBTQ themes. The group’s stated motivation, at least according to comments shared with the Associated Press and referenced by Lit Hub, was safeguarding taxpayer interests and promoting “self rule.” There’s an irony there, considering events soon led to a proposal to hand the library over to an out-of-state corporation.

Following the complaints, Lit Hub reports that Warren County officials, bowing to pressure from the book banners, slashed funding for the library. Samuels Library, in return, stood its ground against efforts to remove books, even as its funding was briefly restored amid community outcry. The real twist arrived this past March, when the Warren County Board of Supervisors decided not to renew funding at all, instead floating Library Systems & Services (LS&S)—a private firm under the umbrella of Evergreen Services Group—as the future operator.

Why the sudden trust in LS&S? The company’s reputation, as outlined in Lit Hub’s review of online coverage and legal spats, seems to hinge less on its capacity to foster literary curiosity, and more on its skill in generating headlines (and headaches) wherever it turns up. LS&S originally launched in the ‘80s dealing in catalog software, riding the broader wave of government outsourcing popularized during the Reagan era. Their business model, Lit Hub highlights, now extends to running the fifth-largest library system in the country, as cited in a 2010 New York Times article referenced by Lit Hub, where their self-proclaimed efficiency means plenty of cuts and the replacement of unionized employees.

Frank A. Pezzanite, the company’s then-CEO, famously diminished the sacred status of libraries and described his approach to staff cuts with candid, not-quite-library-friendly flair. Quoted in the Times and relayed by Lit Hub, he declared, “There’s this American flag, apple pie thing about libraries,” and argued too many libraries operated as unaccountable job havens, contrasting that with LS&S’s more rigorous demands on workers. One might ask: Is there a competitive sport in being the only executive brave enough to pick a fight with a librarian?

The Efficiency Paradox

Samuels Public Library, by the way, isn’t exactly the local paperweight critics would have you believe. As described in the Royal Examiner and noted by Lit Hub, in the previous year alone, the library brought in 2,204 new cardholders, staged 542 programs, and racked up more than 400,000 checkouts. This “atrocious” inefficiency, it seems, also netted them the 2024 Virginia Library of the Year award. If only all public institutions could underperform with such gusto.

Yet in spite of this track record, county officials still tried outsourcing. LS&S, according to its own narrative presented through past media coverage and referenced in Lit Hub, promises to bring order to “messy” civic services—usually through staff reductions and tighter budgets. The phrase “efficiency” appears again and again, as if repetition alone could justify what’s really on offer: fewer librarians, less local input, and a streamlined—but ultimately narrower—idea of what a library should be.

It’s worth noting, as Lit Hub does, that this sort of maneuver plays out with remarkable consistency nationwide. Starve a public service of resources, claim it’s failing, and then sell the solution as privatization—even if communities are already voting with their feet in support of the public option. Is efficiency truly the gold standard for every communal good, or is it just the most convenient metric for those seeking profit?

Preserving the Quirks of Public Service

What comes through clearly in Lit Hub’s narrative is that Samuels Public Library’s greatest defect, at least in the eyes of the efficiency enthusiasts, seems to be its function as a genuinely public institution—one run not for revenue but for residents. As relayed in the outlet, earlier supporters of the book-banning campaign couched their campaign under the banner of “self rule,” only to pivot quickly to out-of-state, for-profit control when local outcomes were not to their taste.

There’s a fundamentally odd tension in demanding both absolute local oversight and the intervention of distant corporate management. If the issue is how public funds are used, as expressed by critics in the AP and cited by Lit Hub, shouldn’t that debate itself remain local, and under the stewardship of a nonprofit like Samuels—a model that’s apparently worked since the John Adams administration?

And what of the people who actually keep the library running? The implication, picked up in previous coverage and noted by Lit Hub, is that decades-long service and institutional memory are liabilities rather than assets. Perhaps it’s easier to imagine a library as a metrics-driven delivery mechanism if you’ve never relied on the wisdom of the person behind the reference desk to track down that impossible-to-find book, or to recommend a read that shifts your worldview.

The Real Bottom Line

Lit Hub makes the case that government institutions—however imperfect—are neither the dens of waste nor laziness they’re often portrayed to be. Efficiency, when translated to mean “profitability above all else,” isn’t always compatible with the broader responsibilities embedded in public life. Sometimes the “waste” is actually capacity: a meeting room open for the community, an experienced librarian paid a living wage, a space where a lonely afternoon can be spent in good company, even if these services don’t jot neatly into a profit-and-loss spreadsheet.

So, what’s to be learned from this episode? When private equity knocks on the library door, it’s typically not out of a sense of civic stewardship. The quick fix of streamlining can be a convenient excuse for stripping away what’s most valuable: the messiness and generosity that only public spaces seem to muster. Even amid funding cuts and outside interference, The Samuels Public Library managed to rally its community, outlast the efficiency experts, and—in a fitting plot twist—prove that public enthusiasm can be remarkably inefficient at fading away.

Perhaps the oddest thing of all? Despite everything, the people who value these messy, non-profitable, slightly ramshackle little institutions refuse to let them go. If that isn’t the true bottom line, what is?