There’s a special kind of story that manages to linger on the edge of explanation—never quite dismissed, but never quite understood, either. For Mike Hoggan, a man who spent 42 years navigating Montana’s rugged pastures as a government trapper, these oddities didn’t just spice up his career; they occasionally unsettled it. In his new memoir, “Between Predator and Prey: Forty-Two Years a Government Hunter,” Hoggan shares detail after detail of daily rural unpredictability, yet none seem to haunt him quite like decades of unresolved livestock mutilations, a topic explored by the Choteau Acantha.

Predators Behaving Predictably, Except When They Didn’t

Woven throughout Hoggan’s stories, as recounted by the outlet, is a familiarity with predators: coyotes earning their reputation, mountain lions testing boundaries, even grizzlies trundling into bee hives. He worked closely with ranchers and wildlife officials, learning the cadence of death on the prairie—when a dead calf is simply the handiwork of a hungry coyote, and when something else is at work. The progression from saddle horses to four-wheelers to helicopters hints at the technological shifts of a four-decade-long career, but some mysteries proved immune to human advancement.

The Acantha highlights not only Hoggan’s preference for a low profile but also his compulsion to document the unusual—he began keeping a notebook of field stories for his children, which eventually grew into a chronicle of the region’s stranger chapters. About half of the book’s tales, the paper notes, unfurl within a 20-mile orbit of Choteau, sowing the land with stories of “crazy sheepherders,” elusive predators, and more than a few episodes that never made the headlines.

The Mutilation Files: Odd, Surgical, Silent

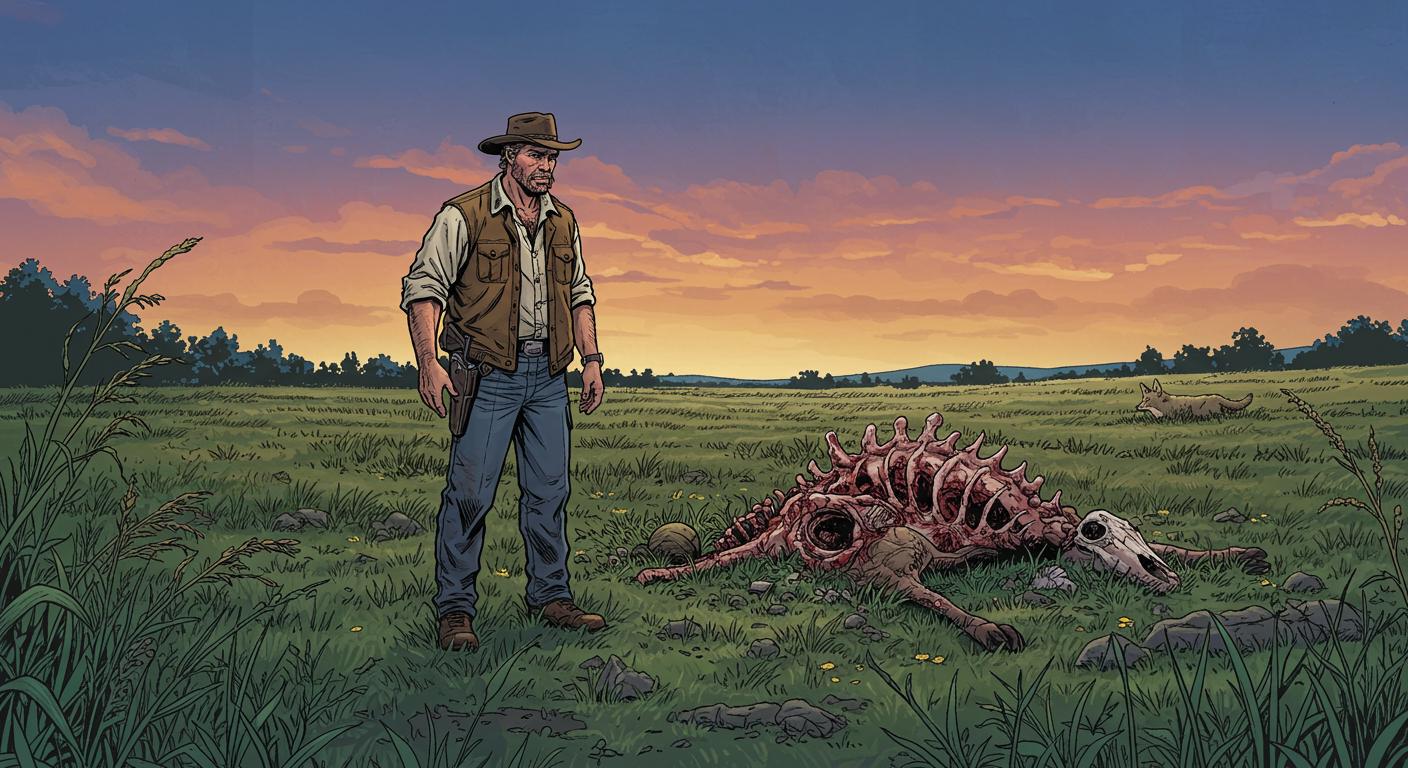

But it’s Hoggan’s experiences with so-called “unexplained mutilations” that most sharply depart from the daily grind of predator control. In a section of his memoir he admits nearly leaving out, Hoggan catalogues a series of livestock deaths that simply refuse categorization. The Acantha describes how, from the early nineties onward, he’d find himself called to the scene of ten to twelve mysterious deaths each summer—episodes followed by quiet spells, then another cluster. He notes that mutilations occurred sometimes in locked pastures, other times in tall grass where there were no vehicle tracks. No sign of human entry, no obvious animal culprit.

Earlier in the report, it’s mentioned that scavengers frequently ignored these carcasses, and that the incisions—skin, organs, even eyes—were removed with what Hoggan described as “surgical precision.” And the mystery wasn’t limited to cattle: bison, sheep, and horses found themselves victims of the same odd fate. Details highlighted by the outlet include Hoggan’s plain assessment: these cases were “definitely” not the work of predators or cults, leaving even this seasoned investigator at a loss. In his own words, “I just couldn’t explain it.”

The paper also points out another odd pattern that stuck with him: the mutilations weren’t steady or predictable. Instead, they came in waves, then would vanish entirely. Each time he thought the phenomenon had run its course, it quietly returned to the landscape, as if determined to outlast rational investigation.

History, Mystery, and Montana’s Wide Open Secrets

Hoggan’s approach, as the Choteau Acantha details, is a careful one. He didn’t seek attention for these perplexities, and he’s blunt about the limitations of his own expertise—he was often called specifically because the deaths didn’t fit any familiar pattern. Even with his background steeped in hard evidence and on-the-ground observation, many of his stories remain open-ended. His wife pushed him to collect them into a book, and it was only after reflecting on the fading of local history that he took up the pen.

There’s a certain symmetry, perhaps, in strange tales choosing to linger in places as wide and unhurried as Montana’s Rocky Mountain Front. The outlet also notes that much of Hoggan’s oddest work happened on the Blackfeet Reservation and in the Dupuyer area, reinforcing the idea that strange happenings have a preference for quiet, remote corners—which, in this case, were never quite as empty as they seemed.

The Satisfying Irritation of the Unexplained

So what are we left with, after four decades and a trail of unsettlingly tidy livestock tragedies? In fact, not much more than we started with. Hoggan’s records, as summarized by the Acantha, offer little in the way of speculation and much in the way of honest confusion. The wounds are described as so precise that the usual theories—secretive predators, elaborate pranks, shadowy organizations—fall flat with a thud. There are no neat conclusions, just a lineup of questions and enough firsthand testimony to ensure it won’t all be dismissed as the stuff of campfire exaggeration.

It’s enough to make you wonder: For every documented oddity, how many more have slipped unnoticed into the long memory of the plains? The beauty (and occasional headache) of stories like these is that they politely defy solution, serving less as evidence for any one theory and more as a reminder that not all phenomena fit the patterns we expect.

For those curious enough to dig beyond easy answers, it’s a situation both unsettling and strangely satisfying. There’s always another wild edge, another unresolved chapter, and—if Hoggan’s experiences are any guide—nobody is immune to the lure of a good mystery.

(For an in-depth look at Hoggan’s career and these cases, see the original reporting in the Choteau Acantha.)