Somewhere between the solemnity of Arbor Day and the sugar rush of the State Fair, Minneapolis’s Lake of the Isles neighborhood has carved out its own peculiar tradition: the annual sharpening of a 20-foot-tall No. 2 pencil, hewn from the remains of a beloved oak tree. As described in an Associated Press report, this is not the sort of small-town festival built on historical necessity or vintage industry—nobody panned for graphite here; no famous exam was ever taken on the shores of Lake of the Isles—but rather an earnest, and deeply poetic, exercise in collective whimsy.

Whimsy on a Grand Scale

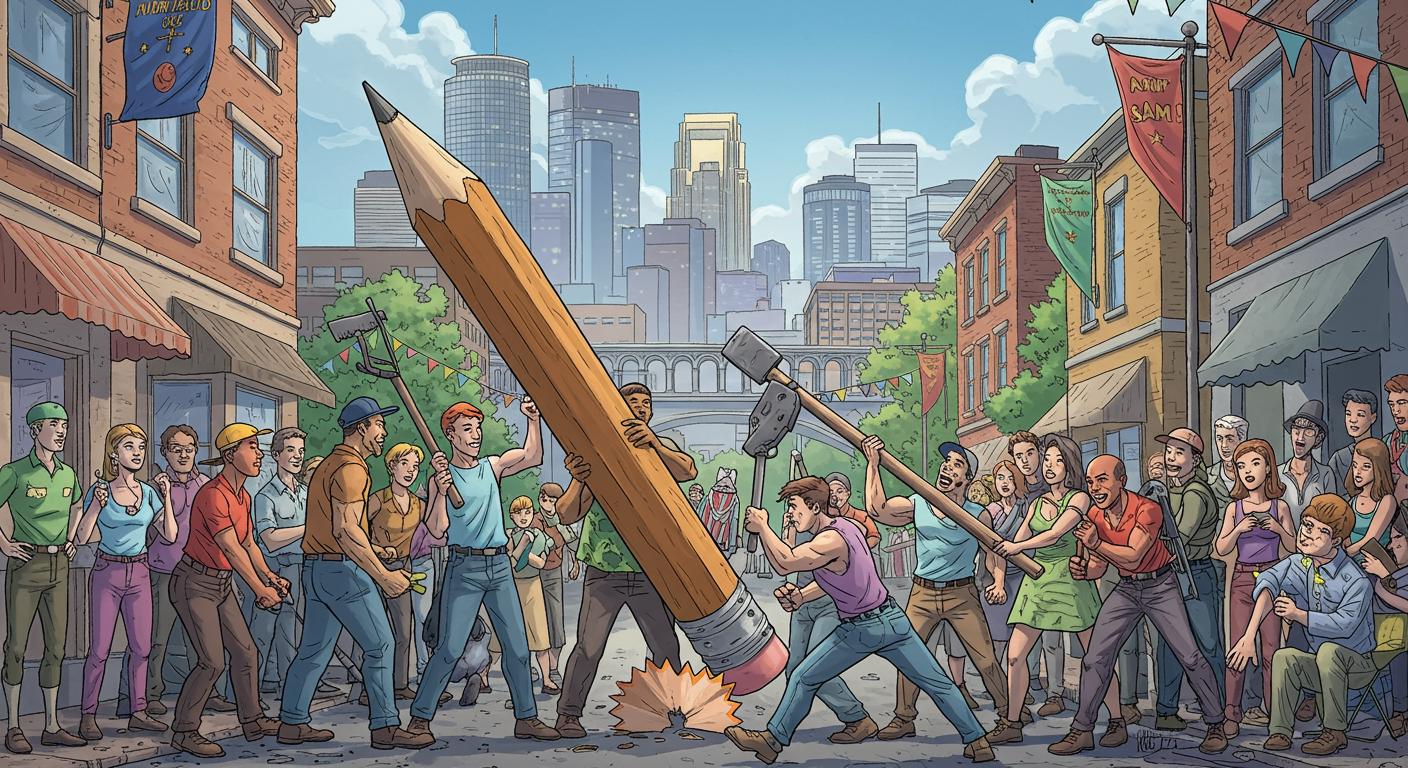

Let’s begin with the facts: what happens is exactly what it sounds like. Hundreds of people, some attired as pencils or erasers (points for commitment), gather every June to witness a ritualistic giant-pencil-sharpening on the Higginses’ front lawn. The ceremonies bring out music, Swiss alphorn players, and, for good measure, purple commemorative pencils handed out in honor of Prince’s birthday. The instrument itself—once a mighty oak, lost to a windstorm—was sculpted into an uncanny replica of the classic Trusty brand No. 2 by wood artist Curtis Ingvoldstad.

According to the article, neighbors interpret the pencil and its annual sharpening in a dizzying array of ways. Amy Higgins noted, “Everybody uses a pencil … You see it in school, you see it in people’s work, or drawings, everything. So, it’s just so accessible to everybody, and can easily mean something, and everyone can make what they want of it.” That everyone can see something of themselves in it seems, in retrospect, inevitable—whether it’s nostalgia, practical utility, or just shared amusement.

Ceremonial Sacrifice and Ephemerality

Rituals, especially the unusual ones, have a habit of accruing significance beyond their initial silliness. As detailed in the outlet, there’s an old-world logic at play in the annual pencil party: the ritual isn’t just about sharpening a giant stick of wood, but about sacrificing monumentality in favor of renewal. Each year, a few more inches come off the tip, and the pencil edges closer to its inevitable stubhood.

Grouping several perspectives together, John Higgins and Curtis Ingvoldstad described this process as symbolic. Higgins pointed out the spirit of starting fresh: “We tell a story about the dull tip, and we’re gonna get sharp,” he said, imagining everything from love letters to to-do lists that could be written with a renewed pencil. Ingvoldstad echoed this, observing, “Like any ritual, you’ve got to sacrifice something … so we’re sacrificing part of the monumentality of the pencil, so that we can give that to the audience … This is our offering to you, and in goodwill to all the things that you’ve done this year.”

The article notes that the event is not about clinging to a static monument. Instead, the neighborhood embraces the pencil’s eventual disappearance with each communal shaving, surrounded by pageantry and laughter.

Drawing Meaning, or Just Doodles?

It’s disarming to encounter a neighborhood festival that doesn’t pretend to be rooted in grand historical necessity, even as it inevitably gathers meaning. The report quotes Ingvoldstad, who welcomes a variety of reactions: people are free to interpret the event however they wish—including, presumably, as an absurd waste of oak. Some rituals might be relics of bygone centuries, but this one is wholeheartedly present: a spontaneous transformation of loss (in this case, a damaged tree) into something both peculiar and memorable.

When, exactly, does a one-off neighborhood stunt transition into tradition? Is it the costumes, the pageantry, the swelling crowds captured in press photos? The event, as outlined in the article, embraces its own transience—the pencil can only be sharpened so long; eventually, it will reach its end point. Perhaps, in building in an expiration date, the ritual is less about maintaining a monument than collectively savoring its gradual disappearance.

And isn’t there a kind of relief in traditions that actually accept their own mortality? When a ritual admits its own absurdity and eventual end, maybe that’s precisely what gives it meaning—the knowledge that the celebration is finite, the communal joy not just permitted, but required, before the point is gone.

The Pencil Is the Point

On paper (forgive the pun), the annual Giant Pencil Sharpening could read as little more than a harmless oddity—one more neighborhood quirk among many. Yet as the AP story illustrates, its appeal reaches a bit deeper. The transformation of a fallen oak into an ever-diminishing monument, whittled year by year, is equal parts performance art, community-building experiment, and an ode to transience.

So is the point of it all simply to keep the pencil sharp? Or, as the story suggests, does the true meaning lie in the collective acceptance of ephemerality—the joys of a ritual you know cannot last? After all, sometimes the oddest traditions are the best reminders that even the simplest things—a pencil, a summer gathering—are most cherished as they slowly, joyously dwindle.