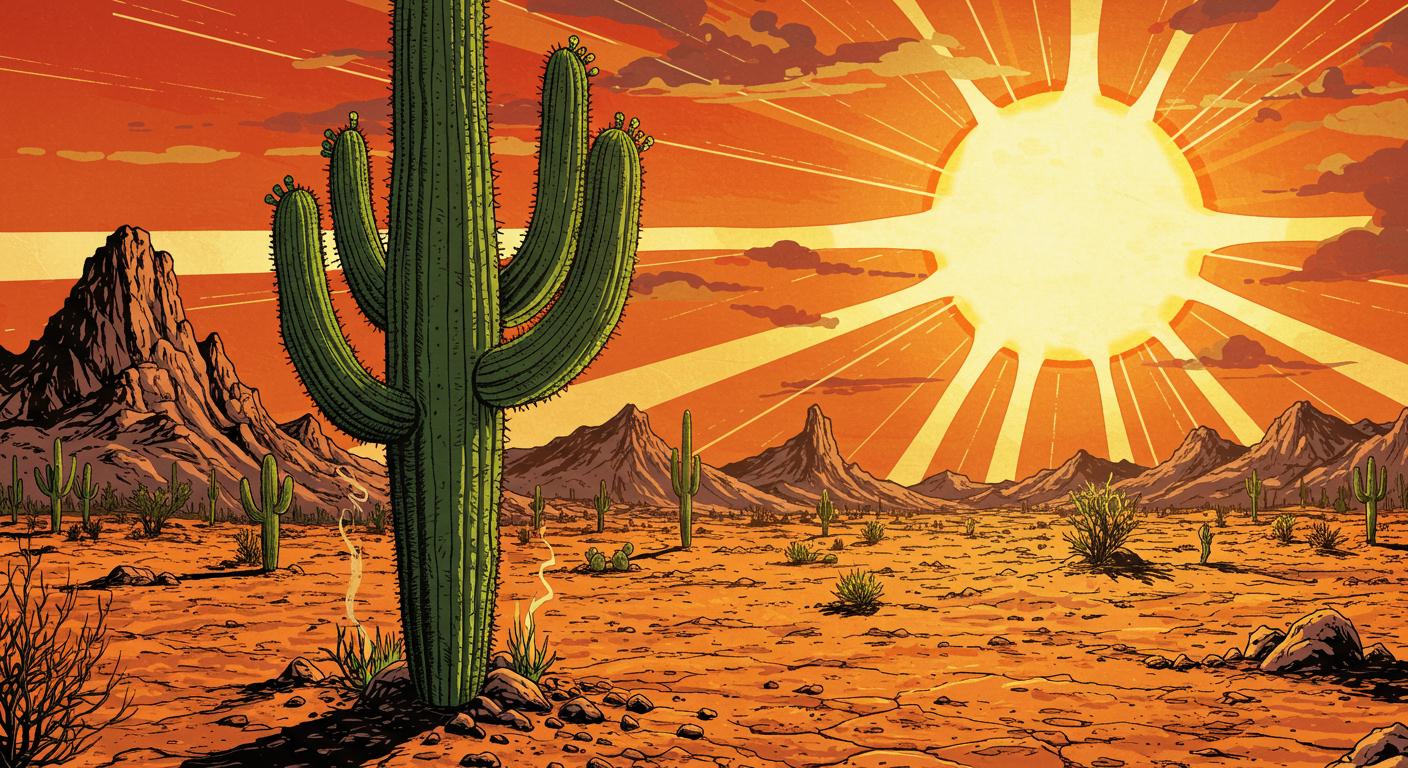

There are a few things in life you expect to be permanent fixtures—the sun rising, taxes doing their dampening work, and, out in Arizona, the saguaro cactus stoically defying all odds. For the uninitiated, the saguaro (those spiky, branching giants that seem perpetually mid-dramatic pose) isn’t just a piece of desert furniture; it’s practically the desert’s mascot. As featured by CBS News in a dispatch from Kris Van Cleave, these plants have weathered everything from centuries of drought to the occasional overeager tourist. But even the saguaro, it seems, has its breaking point—and 2025 may be the year.

When “Built Different” Isn’t Enough

Described in the CBS segment, saguaro cacti have evolved over millennia to withstand Arizona’s extreme climate. No strangers to sun or scarcity, they’ve made their living in the Sonoran Desert—a place where water is a cameo guest star and survival is an extreme sport. Still, as Van Cleave reports, after decades of gradually warming temperatures, even these desert veterans are starting to show unmistakable signs of distress.

It’s an irony that verges on the surreal: according to footage reviewed by CBS News, there are instances of the desert itself now becoming too hot for its native icons. CBS points out that these rising heat levels are pushing saguaros to their physiological limits, challenging the very traits that once allowed this species to dominate some of the harshest places on earth.

The Quiet Meltdown of Giants

Van Cleave’s reporting shows saguaros displaying clear evidence of heat stress: drooping arms, a patchy and unhealthy appearance, and clusters simply not surviving conditions once considered routine. CBS News documents how this isn’t just a seasonal fluke—the cacti, which have been around for centuries, are struggling to adapt to years of intensifying heat and less predictable rainfall. As detailed in the segment, the cumulative pressure of these changes is leading to unexpected die-offs, transforming what should be a slow, stately process into a visual symbol of ecological shift.

When the plant equivalent of a tank starts looking peaky, you know something fundamental is shifting. In fact, earlier in the report, it’s highlighted that decades of persistent climate warming have begun to show up not just in weather graphs but in the downward sag of limbs that once stood defiant.

So, What’s Left If the Saguaro Isn’t?

For many Arizonans—and anyone who’s spent time gazing out over the Sonoran expanse—the saguaro’s presence is not just scenery. As CBS notes, these giants are memory anchors, cultural touchstones, and silent sentinels. If the saguaros are now, in the words of the outlet, “showing signs of stress,” who exactly is standing guard over the rolling, sun-baked openness of the desert?

There is a kind of humility in watching these supposed immortals succumb to the slow boil of environmental change. Is there, perhaps, a message buried in a century-old cactus drooping against the skyline? When the things designed to outlast sandstorms and droughts start bowing out, it prompts a reconsideration: is anything truly climate-proof?

Earlier in the CBS segment, Van Cleave underscores it’s not a cataclysmic moment but a gradual, widespread trend—a subtle, persistent decline rather than a single dramatic event. The story here isn’t in the explosion, but in the slow, silent retreat.

“Survival of the Fittest” Isn’t Always Uplifting

There’s an odd sort of melancholy in the slow decline of the saguaro. Footage reviewed by CBS News shows these once-mighty columns of green architecture slowly losing their grip on the land they defined. They resemble, now more than ever, grandfathers in a Homeric poem or superheroes at the end of a long run: designed to endure but not, it turns out, invincible.

So perhaps the next time you see a photograph of a saguaro—or, if you’re lucky, an actual one still standing in quiet witness—it’s worth an extra pause. Are we watching, in real time, a living monument bow out? Or is the saguaro simply the latest addition to that growing list of “things we thought could handle anything”?

If the planet is getting too hot for its own cacti, what are the odds for the rest of us?