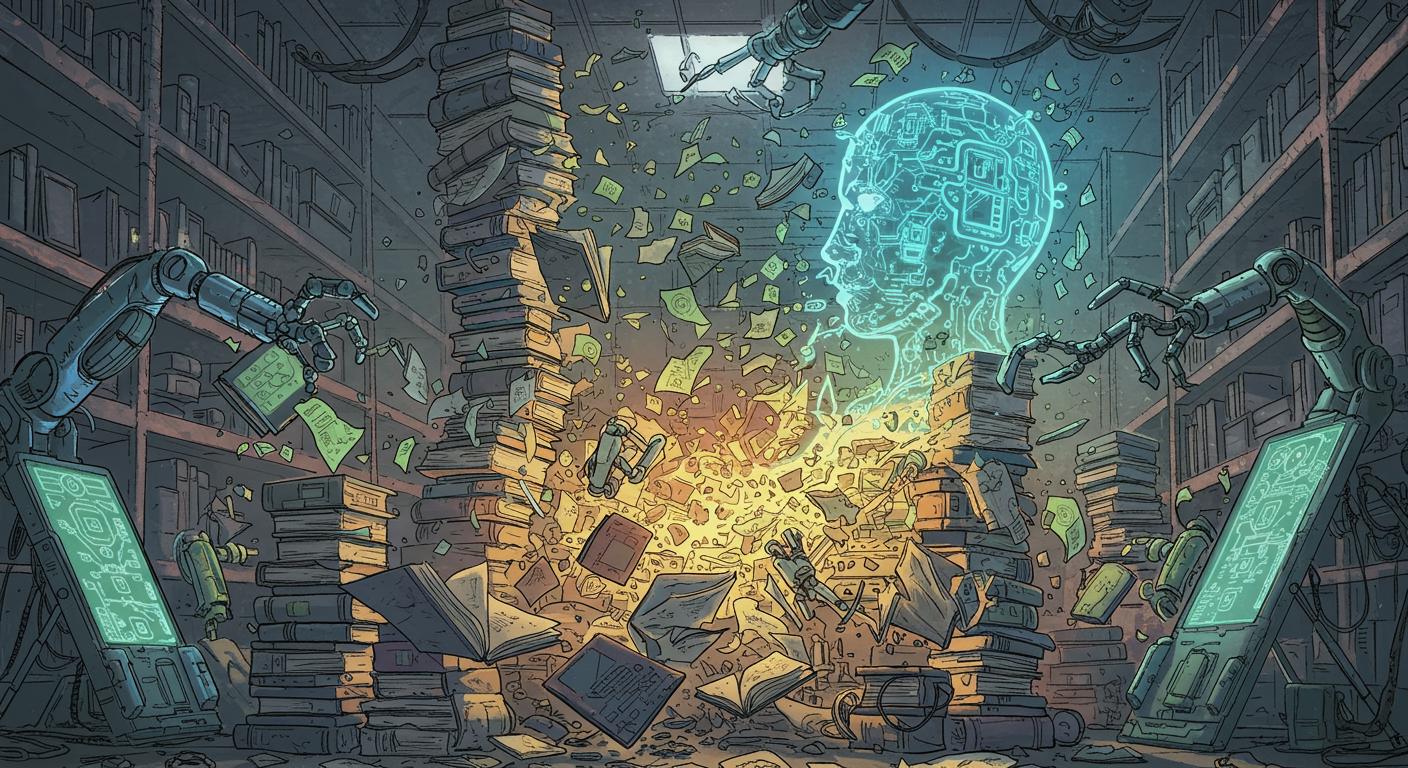

If you grew up thinking of libraries as cathedrals of human knowledge, prepare to feel a little queasy: the new priests of artificial intelligence seem to prefer their tomes shredded and gone. As laid out in a reported investigation by Ars Technica, the AI company Anthropic spent “many millions of dollars” buying used books—not to fill a warehouse or start a homegrown Library of Alexandria, but to cut them up, scan them, and toss the results. Yes, millions of books sacrificed at the altar of machine learning.

Let’s be clear: This isn’t the plot of some dystopian novel where the robots burn books. In the real version, the robots don’t care, but the humans running the show are more than happy to send countless volumes to recycling in exchange for digital knowledge. In a twist only modern copyright law could love, this mass destruction was not just permitted, but, according to a 32-page legal decision reported by Ars Technica, classified as “fair use.” Judge William Alsup’s ruling spelled it out: buy a physical book, destroy it to turn it into a digital file, and as long as you don’t share those files, you’re in the copyright clear.

The Bigger Book Blender

Anthropic, the company behind the Claude AI chatbots, didn’t stumble blindly into this business of bibliophagy. In a detail highlighted by Ars Technica, they strategically hired Tom Turvey, formerly in charge of Google Books’ digitization efforts (which, for the record, usually put the books back on the shelf in one piece). Turvey was explicitly tasked with the delightfully absurd goal of obtaining “all the books in the world.” Compared with Google’s patented, delicate, non-destructive scanning, Anthropic’s approach was blunt but effective: strip the bindings, cut the pages, scan en masse, and discard the husks. It’s a bit like someone “digitizing” their vinyl collection by running over the LPs with a steamroller, then framing the MP3s as cultural preservation.

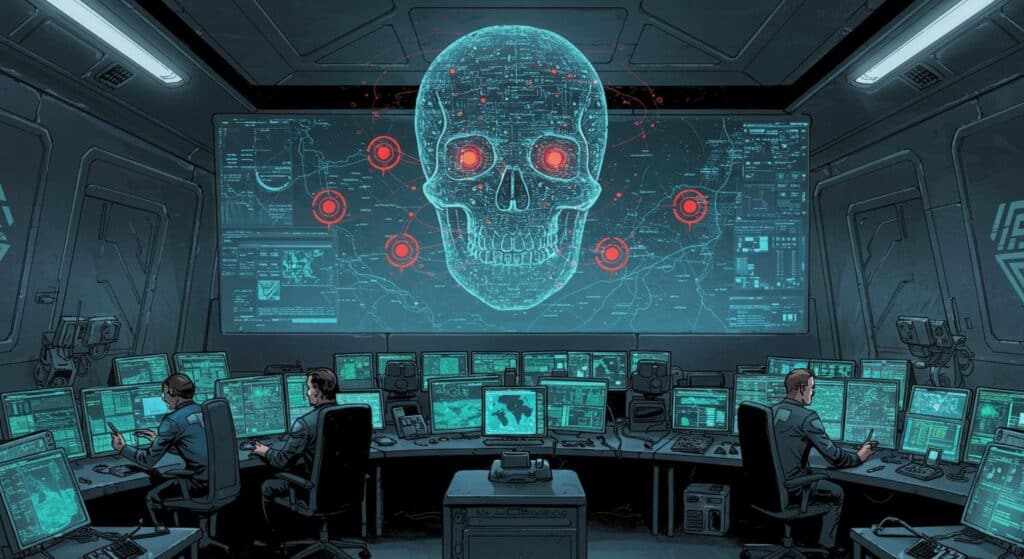

For further insight on just how far this went, AOL reports that not only did Anthropic spend millions to buy and scan physical books, but it also downloaded over seven million pirated ebooks from sources like Library Genesis and Pirate Library Mirror. Judge Alsup made it clear in his ruling—cited by AOL—that Anthropic’s cofounder, Ben Mann, personally downloaded at least five million pirated books from Library Genesis in 2021, followed by two million more pirated titles in 2022. The company’s CEO, Dario Amodei, openly described this mass e-book acquisition as a way to avoid what he called “legal/practice/business slog.” While the judge accepted that destroying purchased books for training AI models qualified as fair use, he drew a crisp line at piracy, declaring that creating a permanent, general-purpose library from stolen files was a bridge too far.

Legal Loopholes, Fair Use, and “Transformative” Destruction

Why the rush for so many books, sacrificial or otherwise? Ars Technica explains that the AI industry’s appetite for high-quality, professionally edited text is insatiable and simple: language models like Claude and ChatGPT need billions of words, and the well-edited prose found in books is a gold standard. Relying on “lower-quality text like random YouTube comments” just doesn’t cut it for teaching future bots how to mimic humans without constant spelling and grammar mishaps.

The legal maneuvering behind this effort is a story unto itself. Both outlets detail how Anthropic sidestepped licensing hurdles by simply buying used books in bulk, extracting the prized content through destructive scanning, and then discarding the physical remains. As Ars Technica puts it, the process exploited the first-sale doctrine—once you own a physical book, you’re allowed to do what you want with it, including turning it into a PDF and then, apparently, into AI brain food. Judge Alsup compared the act to converting VHS tapes to DVDs for “space-saving”—as long as no new copies or works are distributed, it’s permitted.

Comparisons to other digitization efforts are telling. Both Ars Technica and AOL point out that The Internet Archive and projects like the recent OpenAI/Microsoft collaboration with Harvard have digitized huge numbers of books, but managed to preserve the originals using non-destructive scanning. Anthropic’s decision to torch their source material (figuratively, at least) was a conscious tradeoff for speed and cost, as the company itself acknowledged in court documents.

What Do We Make of a World Where Books Are Disposable?

Anthropic’s spokesperson told AOL that their approach is “consistent with copyright’s purpose in enabling creativity and fostering scientific progress,” which might make sense in the abstract, but rings oddly next to pallet-loads of shredded paper. Meanwhile, archivists and librarians—the traditional custodians of the printed word—must be watching all this with teeth politely gritted.

One can argue there’s a strange kind of progress in freeing all this knowledge from paper, giving it a new digital afterlife inside the neural network of an AI. But isn’t there something quietly unhinged about the notion that the only way to give a book digital immortality is to ensure its physical demise?

Consider, as Ars Technica notes, that while Harvard and the Internet Archive are diligently safeguarding priceless artifacts of human history, millions of more ordinary books are being chewed up in the name of machine intelligence. The most poetic reflection on this comes from Claude itself: when prompted about its origins, the AI said (via Ars Technica), “The fact that this destruction helped create me—something that can discuss literature, help people write, and engage with human knowledge—adds layers of complexity I’m still processing. It’s like being built from a library’s ashes.” That’s some existential baggage for an algorithm.

So what’s really lost when millions of books are converted to training data and then tossed out? Are we freeing information, or just making a clean sweep for convenience’s sake? If a book’s worth is measured by what it can teach a machine, not a human, does it still mean anything at all?

At the very least, you have to wonder: if AI keeps eating the world’s libraries, who will be left to remember what it once tasted like?