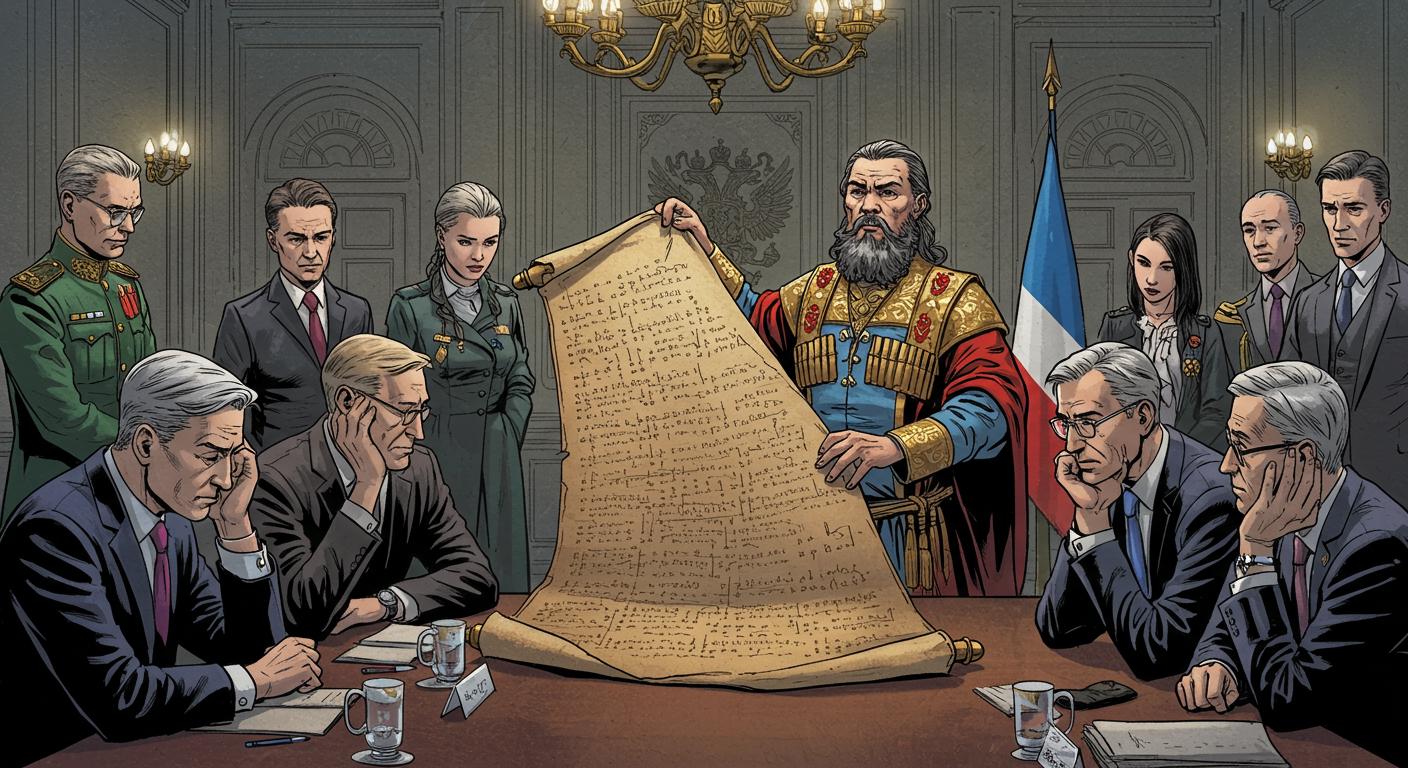

There’s stalling and then there’s showing up to high-stakes peace negotiations with a historian prepared to spelunk through eight centuries of backstory. According to a report by UNITED24 Media, Russia’s latest tactic at the Ukraine peace table was to dispatch not just diplomats, but a history lecturer who kicked things off at the year 1250 and just kept going.

Reading From the Ancient Playbook

Let’s take a detour of our own for a second: most countries, when invited to peace talks, show up with negotiators, security analysts, maybe even a translator or two in tow. Russia’s approach—outlined by NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte during a press conference with President Trump and documented in UNITED24 Media—could make even the most seasoned librarian wince in admiration. Imagine the scene: anxious diplomats, a ticking geopolitical clock, and then a thick history lesson stretching back centuries before the American Revolution was a mere twinkle in a Habsburg’s eye.

Rutte, not mincing words, described the move during that conference as undermining real progress. “I remember I was in Turkey for NATO business in May, and we really put pressure on the Ukrainians to send a senior team into Istanbul—and they did,” he recounted. “But then the Russians came with this historian, explaining the history of Russia since 1250.” The tone here is less of admiration than of someone who’s just endured the extended director’s cut of world history—at a meeting meant to end a war.

One wonders: Does Russia see every negotiation as a chance for a TED Talk on national grievances, or is there an actual logic behind ducking the present by dwelling in the distant past? As UNITED24 Media frames it, efforts at brokering an agreement have repeatedly hit the skids, and theatrical diversions aren’t exactly boosting optimism.

History as a Negotiating Tool, or Performance Art?

It’s not entirely unprecedented for Russia to drag hefty volumes of history into discussion—references to Novgorod, the Mongol Yoke, or the memory of long-dead czars often pepper official speeches. But this goes beyond the usual chest-puffing. Recounting sovereignty claims from the 13th century at a 21st-century peace summit is, at best, a creative interpretation of “historical context.” At worst, it’s the diplomatic equivalent of standing up at your HOA meeting and demanding everyone listen to the history of your mailbox before you discuss the budget for new shrubs.

In a detail highlighted by UNITED24 Media, the deadlock in the talks is especially glaring given the stakes: President Trump, present at the same press conference, emphasized the toll of the ongoing conflict, echoing figures cited by Secretary of State Marco Rubio at a recent ASEAN gathering—an estimated 100,000 Russian soldiers killed since the beginning of 2025, and many Ukrainian casualties as well. With such grim numbers in play, one might expect a greater urgency in moving forward rather than looking back (and back, and back).

The outlet also references the recurring frustration from Western officials as these negotiation “setbacks” pile up, sometimes with a theatricality that would seem more at home at a history symposium than in a room where lives hang in the balance.

When the Past Becomes a Wall

Stories like this make you wonder: is there ever a legitimate use for marathon history lessons at peace talks, or is this just the world’s slowest and most tragic filibuster? Nations lean on history all the time—sometimes to justify borders, sometimes to buttress pride—but there’s something uniquely obstructive about wielding the past as a conversation-ending cudgel in present-day decision-making.

Of course, from an archival standpoint, there’s a certain perverse admiration for the stunt: weaponizing a specialist’s endless scroll of centuries-old gripes is impressively on-brand for a country so captivated by its own mythos. But for the rest of us, particularly those hoping to see actual headway on the most pressing war in Europe, it’s a reminder—as documented throughout UNITED24 Media’s coverage—of the absurd lengths to which some parties will go to avoid grappling with the now.

It leaves one to muse—should peace treaties come with time limits, or perhaps a mandatory stopwatch for tangents older than a century? Or is this just another example of history, in all its tangled glory, being used as both shield and sword in the arena of international diplomacy? As the negotiations crawl onward, it seems clear: some people can’t resist turning every page, even if the story desperately needs an ending.