There are reminders that squint at the edges of believability, and Harrison Ruffin Tyler’s recent passing is one of those: the last surviving grandson of President John Tyler—America’s 10th commander-in-chief, born merely five years after the ratification of the Constitution—died this week at age 96. This news, covered in detail by NPR, doesn’t just throw open a window into one family’s long shadow; it quietly jolts our sense of how close the past really is.

A Family Tree That Stretches Through Centuries

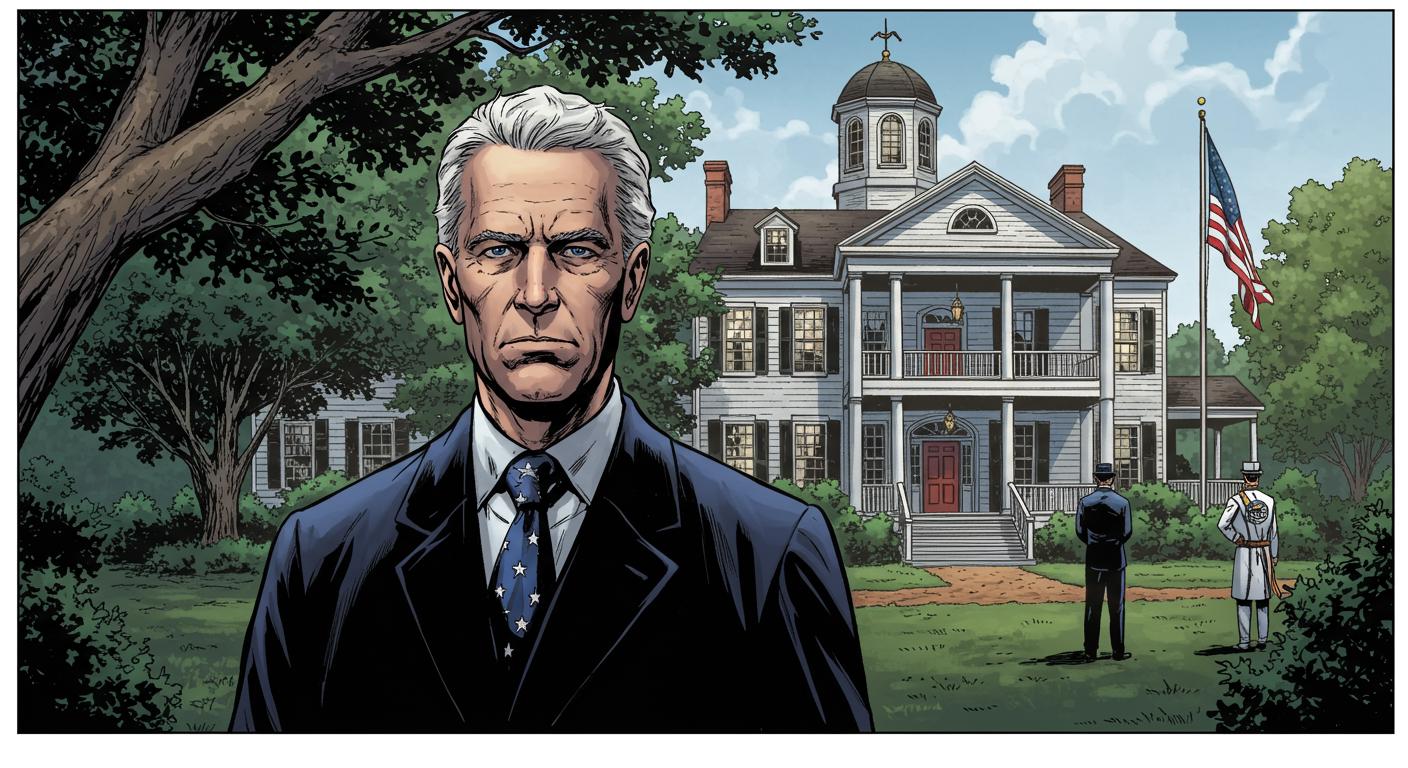

Harrison Tyler’s life began in 1928, his grandfather’s presidency ending more than 80 years beforehand. That generational sleight of hand—rooted in John Tyler’s and his son Lyon’s firm commitment to late-in-life fatherhood—allowed a living, breathing tie to an era more associated with quills and waistcoats than smartphones and streaming. Annique Dunning, executive director of Sherwood Forest (the Tyler family estate), told NPR that Harrison died of natural causes after several strokes, surrounded by a property and history he worked hard to preserve.

There’s a bit of familial time travel at play: Lyon Gardiner Tyler was born when his own father was 63, and Harrison arrived when Lyon was 75. As the outlet details, this left those “how am I my own grandfather’s contemporary?” moments less an abstract thought experiment and more a fixture of daily life. Harrison himself, reflecting in a 2012 interview archived by a Richmond CBS affiliate, admitted it felt “somewhat incredulous” to have a direct line to someone born in the 1700s.

But did he always dwell on it? Not exactly. Tyler once shared with Subaru Drive Magazine that, during his youth in the anxiety-ridden days of World War II, presidential ancestry wasn’t exactly dinner table conversation. Only later in life, as media inquiries increased, did he lean into the historical novelty and familial pride. Is it amusing or faintly surreal, to be asked about Andrew Jackson-era relatives while deciding what to order for lunch?

Chemical Equations and Preservation Projects

NPR outlines how Harrison Tyler charted a course in chemical engineering, not politics, earning a scholarship to William & Mary at just 16. Interestingly, his family’s storied past didn’t guarantee material comfort; his son William once explained to the Washington Post that much of the Tyler wealth was “tied up in a vast book collection” donated to the college, and Harrison’s tuition was mysteriously covered by Lady Astor, a woman the family had never met.

After college, Tyler helped found ChemTreat, an industrial water treatment company that, before its acquisition by Danaher Corporation in 2007, reported $200 million in annual revenue. Tyler told Virginia Tech Magazine in 2007 that their philosophy boiled down to a simple, effective formula: “sell a product that works, hire good employees, and take care of those employees.” That practical, collaborative spirit led to an employee-owned structure by 1989—an uncommon move, and one with significant consequences for the company’s workers when Tyler and his business partner retired in 2000.

It wasn’t just business where Tyler left a mark. With his wife, Frances Payne Bouknight Tyler, he bought back Sherwood Forest from cousins in the mid-1970s, taking on the colossal task of restoring a house whose walls probably held more stories—and secrets—than anyone could catalog. Letters and mementos from past Tylers guided their restoration, and, as NPR observes, half the house (and its alleged ghost, the Gray Lady) now opens to public tours, blending family stewardship with a cautious public reckoning of its antebellum and Civil War history.

Tyler’s appetite for preservation also extended to Fort Pocahontas, a Civil War fort that had sat untouched for over a hundred years before he purchased and helped open it for public reenactments. In a nod to legacy complicated by history, the College of William & Mary recounts how a $5 million endowment by Tyler ensured ongoing research across subjects, including the histories of slavery, racism, and discrimination—an especially pointed gift given his father’s staunch pro-Confederate sympathies.

Navigating Legacies—With or Without an Instruction Manual

Legacy, especially a national one, is rarely tidy. John Tyler’s name is as likely to conjure up his feud with the Whig Party and the annexation of Texas as it is his late-life advocacy for the Confederacy. Lyon Gardiner Tyler’s own views on slavery and secession made his association with modern educational institutions problematic enough that, as NPR reports, history scholars at William & Mary shifted the honorific on the family endowment from father to son in 2021.

Even so, Harrison Ruffin Tyler’s approach, described in several interviews, was more about context than absolution. He pointed out—perhaps in defense, perhaps as an attempt at nuance—that his grandfather worked to organize a Peace Conference in hopes of averting civil war. When that effort failed, John Tyler was indeed elected to the Confederate Congress, though death intervened before he could serve.

Asked, with a wink, whether he planned to continue his forebears’ tradition of late parenting, Harrison shut that conversation down: “We’re not going that route again.” Sometimes, drawing the line is the truest act of inheritance.

How Far Away Is “Old News,” Really?

It’s tempting to relegate tales like this to the realm of the quirky—fodder for a trivia contest, or a family anecdote told at Thanksgiving—but the deeper strangeness has staying power. If only two generations separate founding-era America and today’s world of electric cars and meme stocks, perhaps the notion of “ancient history” isn’t quite as impenetrable as we sometimes pretend. How many living people in your own orbit can trace memories, customs, or stubborn quirks across similar, astonishing stretches of time?

Harrison Ruffin Tyler’s passing invites us to examine what’s handed down: not just property or anecdotes, but the tangle of pride, accountability, and difficult questions that come with family ties to long-ago events. Legacies, it turns out, are both persistent and elastic, shaped by what we restore, what we revise, and what we’re willing to admit was never fixed in the first place.

So the next time someone writes off a story as “ancient history,” it might be worth asking—do you really know how close the past sits, just behind your neighbor’s front door?