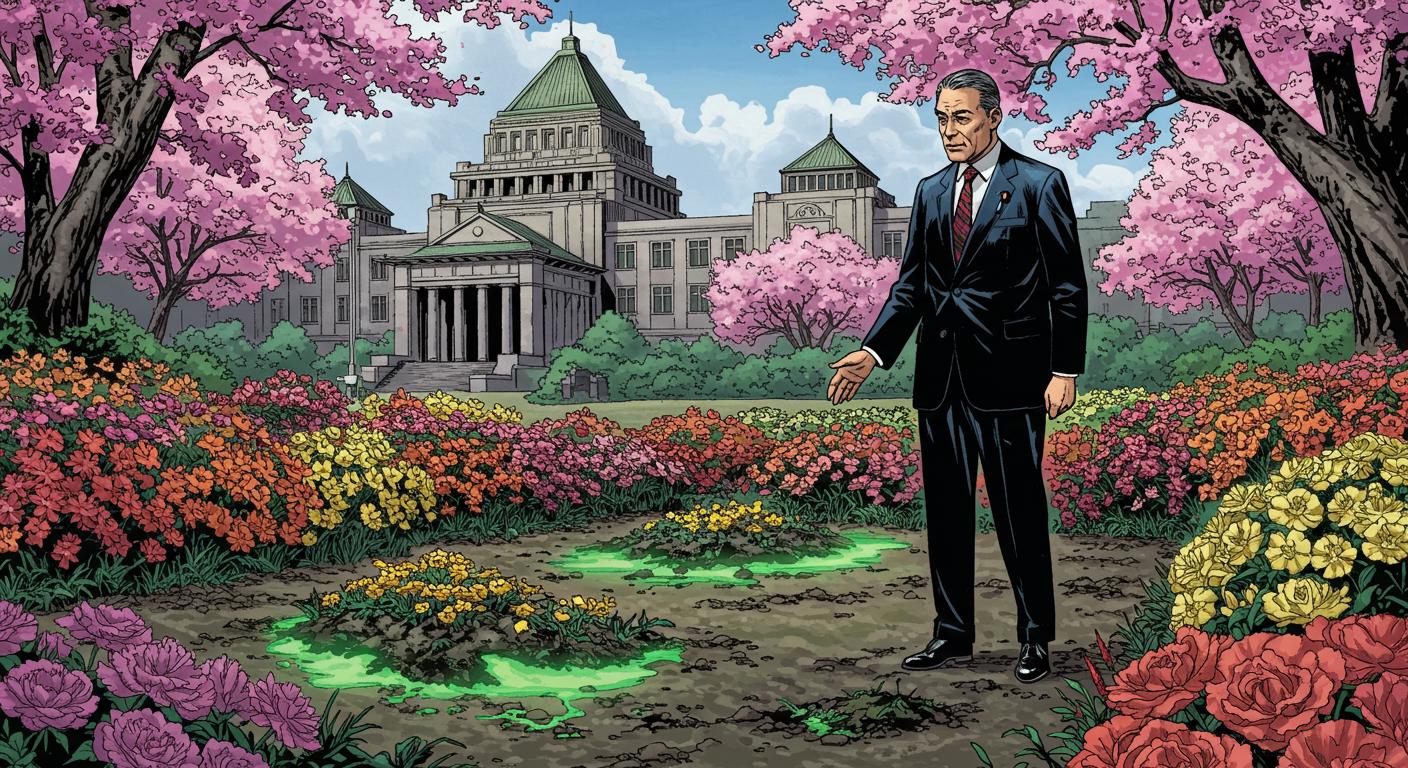

In the long tradition of governments opting for bold (and occasionally baffling) demonstrations of confidence, Japan’s latest plan to reassure the public about Fukushima’s post-disaster soil might take the floral cake. According to the Associated Press, the government will soon break ground on a very public gardening project: flower beds around Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba’s office featuring “slightly radioactive” soil, straight from storage near the former Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant. Yes, the soil has passed safety checks—government scientists are nothing if not thorough—but there’s no denying the symbolism is as robust as a well-fed chrysanthemum.

From Temporary Storage to Center Stage

This dirt’s backstory is a saga of its own. As documented by the AP and further detailed by The Goshen News, roughly 14 million cubic meters of such soil—enough to stuff eleven baseball stadiums—was removed from across Fukushima Prefecture during the sweeping decontamination following the 2011 nuclear disaster. For years, it’s sat in sprawling interim sites on the outskirts of towns like Futaba and Okuma. Now, thanks to a blend of time, remediation, and government optimism, portions of this stockpile reportedly meet reuse criteria outlined in guidelines from Japan’s Environment Ministry, which received a stamp of approval from the International Atomic Energy Agency.

Officials at a recent soil task force meeting, as noted in the AP’s coverage, described the upcoming project as just the beginning. The government aims to extend the experiment to other public works—roads, perhaps, or future landscaping for other agency buildings—but will first focus on the Prime Minister’s office as a high-profile proof of concept. It’s a play straight from the “lead by example” handbook, though one imagines more than a few citizens are clutching their metaphorical Geiger counters.

An additional mention in ABC’s syndicated technology news emphasizes that the soil for these plantings has never been inside the nuclear plant itself—likely an important detail for anyone worried about their snapdragons developing extra petals.

Radiation Remediation, Topsoil Edition

So how does one safely bedazzle a garden with post-Fukushima earth? Authorities told the AP that the “slightly radioactive” soil will form a base layer, carefully sealed beneath ample topsoil designed to ensure that any measurable radiation at the surface is “negligible.” This sandwich approach is by no means a DIY experiment—expect multiple safety protocols, environmental monitoring, and likely a little more caution with weeds than usual.

And yet, as much as government officials tout the effort as scientifically sound—pointing to data, ministry guidelines, and IAEA approval—there’s a clear sense of public meltdown fatigue. In a detail highlighted by The Goshen News, prior attempts to pilot similar soil reuse projects in public parks around Tokyo fizzled after vocal opposition, a sign that anxiety can be far more stubborn than dandelions.

Complicating matters, the AP reports that the government faces looming deadlines: A promise to find permanent disposal sites for Fukushima soil outside the prefecture by 2045 still stands. Until then, vast heaps of bagged dirt wait in open limbo, while officials float proposals to use the lowest-risk material as filler under roads or in other, less politically fraught infrastructure.

Petunias, PR, and Public Perception

Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshimasa Hayashi, speaking at the soil task force, called for coordinated efforts to promote “understanding” and showcase safe demonstrations—starting with none other than the Prime Minister’s technicolor landscaping. The outlet also notes that, although the roadmap and launch date for the project are yet to be finalized, the symbolism is already growing roots. After all, if you’re set on persuading a wary public to accept reimagined uses for Fukushima’s legacy, what’s more visually low-stakes (and high-profile) than flowers on the nation’s metaphorical front lawn?

Still, as ABC’s reporting underscores, the ghosts of past nuclear accidents linger in the public consciousness. The 2011 disaster left lasting scars: entire towns still off-limits, massive volumes of decontamination debris, and ongoing debates about the safety of water, soil, and the legitimacy of official reassurances. Japan’s efforts to manage this legacy—such as last year’s discharge of treated wastewater into the ocean, described in previous AP reports—reliably spark everything from measured concern to out-and-out protest.

A Glowing Example, or Just Wishful Watering?

It’s hard not to appreciate the darkly poetic logic underpinning this campaign of confidence. Will a prim, blooming border around the PM’s office convince anyone that the legacy of Fukushima is truly under control? Or will people simply marvel at a new category of government landscaping project: “radioactive, but in a good way”?

In a country where the line between reassurance and performance is often fine (and occasionally blurred with topsoil), this garden experiment feels less like floral bravado and more like carefully cultivated optimism. Still, you have to wonder—in years to come, when the petunias are thriving and the soil has settled, will the memory of Fukushima’s dirt finally seem less daunting? Or will the shadow of “slightly radioactive” remain, despite the blooms?

If nothing else, public relations by petunia is a fresh chapter in the long, strange history of nuclear communication. Sometimes, the most surreal stories are the ones that flower right outside the front door.