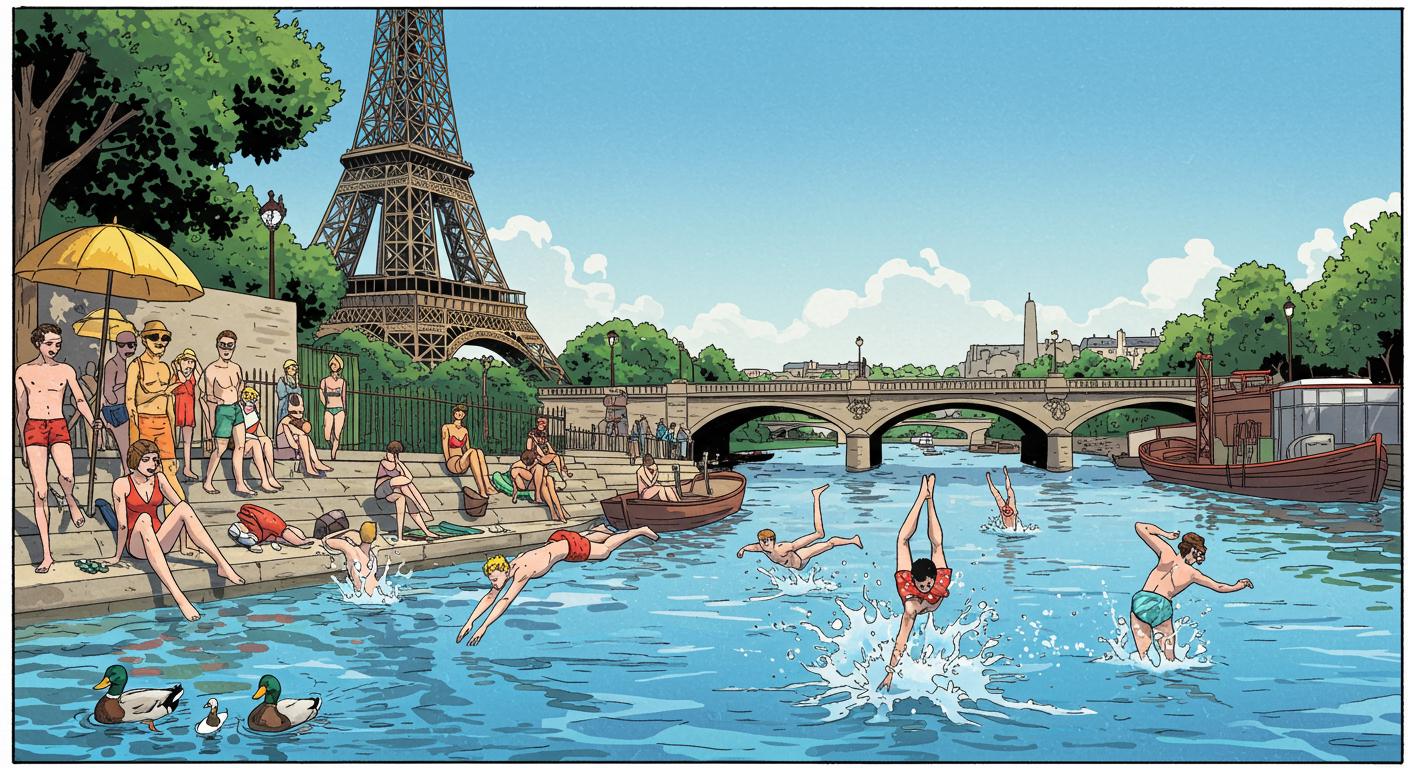

There are certain universal constants: gravity, taxes, and the belief that the River Seine is lovely to look at but—unless you have a strong immune system and a desire for the unexpected—should never, ever be entered bodily. For most of the last hundred years, this wasn’t just good advice; it was the law. Yet, in a move that would surprise 1920s Parisians (possibly even more than smartphones), public swimming in the Seine is now officially back on the menu.

As reported by the Associated Press, beginning this July, Parisians and visitors alike are invited to take the plunge at three sanctioned riverside swim sites, all thanks to a city-led effort involving a staggering €1.4 billion cleanup of one of the world’s more storied watercourses.

Washed Away: A Century’s Worth of Grime

Swimming in the Seine has technically been off-limits since 1923, “with a few exceptions, due to pollution and risks posed by river navigation,” the AP explains. The reasoning was less about Victorian prudery and more about the river rapidly becoming a frothy street for sewage, debris, and the occasional unlucky bicycle. The ban made sense, and with the passage of a hundred years, few were clamoring for its return—outside of the odd daredevil or, more recently, Olympic athletes contractually obligated to test the city’s handiwork.

In detail highlighted by the Associated Press, Paris didn’t just toss up a few warning buoys and hope for sunny weather. Ahead of the 2024 Olympics, city authorities commissioned massive new disinfection plants and a huge storage basin intended to intercept bacteria-laden wastewater, particularly during storms. The outlet also notes that houseboats and upstream homes were required to connect their wastewater to the municipal sewer system, closing one more loophole in the city’s ongoing battle with river pollution.

This is the sort of infrastructural effort that rarely makes headlines—unless, of course, a triathlon gets rained out due to bacteria spikes, which, as AP reports, indeed happened during the Olympic competitions when rainfall drove bacterial levels high enough to postpone events.

Confidence, Skepticism, and the Murky Middle Ground

Standing at the riverbank today, it’s a collision of conflicting realities. Olympic glory and official pronouncements are on one side. Sports coach Lucile Woodward, who told the Associated Press that “it’s a symbolic moment when we get our river back,” will be among the first to compete in amateur open water events. In her assessment, the proof will be in the splashing: “Once people see that hundreds can have fun, everyone will want to go!” She added, “for families, going to take a dip with the kids, making little splashes in Paris, it’s extraordinary.”

On the less enthusiastic end, you have skeptics like Dan Angelescu, CEO of water monitoring firm Fluidion, whose insights were also shared with the AP. Angelescu warns that although the city’s tests show compliance with European regulations, the official testing “has limitations and undercounts the bacteria.” He explained that “there are only a few days in a swimming season where I would say water quality is acceptable for swimming” and pointedly remarked, “the science today does not support the current assessment of water safety… there is major risk that is not being captured at all.”

As the outlet previously documented, some Parisians find the prospect less about fear and more about basic hygiene. Real estate agent Enys Mahdjoub told AP he wouldn’t be afraid to swim but confessed he’s “a bit disgusted,” tempering any adventurous feelings with, “It’s more the worry of getting dirty than anything else at the moment.”

A glance at the water, with its distinctive murky hue and occasional floating litter, doesn’t exactly recall those untouched alpine lakes. Yet, Deputy Mayor Pierre Rabadan told the Associated Press that water quality now gets the daily green or red flag treatment, just like on French beaches. According to Rabadan, “green means the water quality is good. Red means that it’s not good or that there’s too much current,” and results have reportedly been in line with European health standards since early June, except for two rainy or boat-disturbed days.

Last year, as the AP notes, several athletes became ill after competing in the Olympics, though no definitive link to the river was confirmed. According to World Aquatics, the competitions met their accepted thresholds and the organization praised the Olympic cleanup legacy, saying it’s a “positive example of how sports can drive long-term community benefits.”

Is This the Parisian Summer of Your Dreams?

For now, those keen to test the waters can do so for free at the three approved locations, all under the watchful gaze of lifeguards and with age restrictions—swimming is open to anyone over 10 or 14, depending on the site, the AP states. Clea Montanari, a Paris project manager, characterized the change as “an opportunity, a dream come true,” telling the outlet, “it’d be a dream if the Seine becomes drinkable… but already swimming in it is really good.”

Whether this marks the beginning of a new era for city swimming or just a hopeful experiment remains to be seen. It’s hard not to admire the ambition. Cleaning a river that’s been collecting the city’s gritty excesses for generations is no small feat. The symbolism, too—reclaiming the river for actual people, not just passing boats or history buffs—has a genuine resonance. But on the banks, you can’t help but wonder: will Parisians ever see the Seine as something you want on your swimsuit, or will the old wariness win out?

Perhaps, in the end, the most Parisian thing about this whole affair is the balance between hope, skepticism, and an unwavering commitment to style—swim cap, nose plugs, and all.