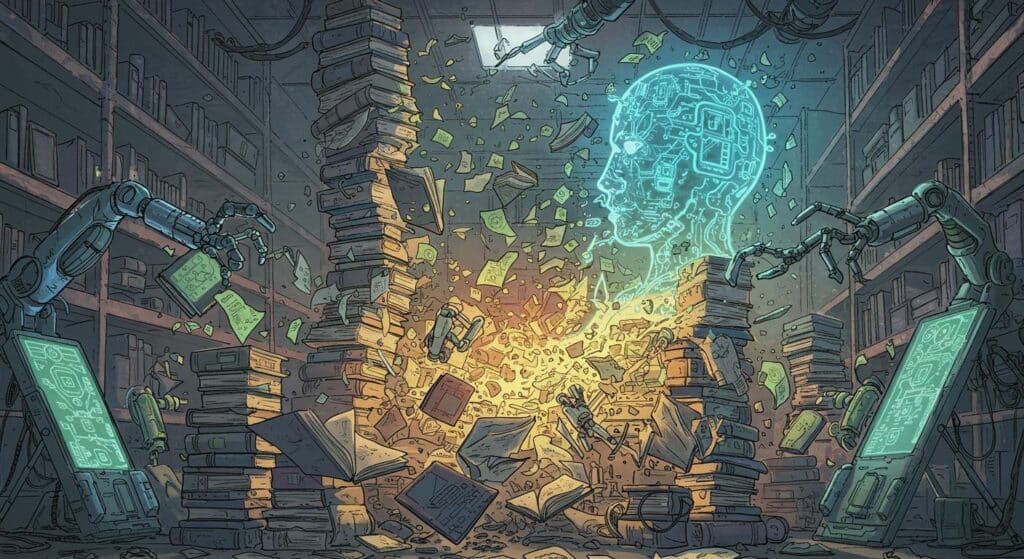

There’s a particular kind of dread that comes with watching science fiction edges blur into reality, and few cases hit quite as close to home as the U.S. government naming a real-world surveillance project “SKYNET.” For anyone harboring vintage nightmares about futuristic AI launching a robot apocalypse, this scenario trades in Schwarzenegger for sprawling databases and drones—but the tension is strangely familiar.

Algorithmic Suspicion, Real Consequences

Tracing the story through a Benton Institute summary of reporting by Ars Technica and The Intercept, SKYNET is essentially a massive experiment in algorithmic suspicion. Documents published by The Intercept reveal the NSA engaged in sweeping surveillance of Pakistan’s mobile phone network, processing metadata from an estimated 55 million people. In a detail flagged by Ars Technica, this information was run through a machine learning algorithm designed to score each person’s probability of being a terrorist, all based on patterns in their call and text logs—who contacted whom, when, and how often.

Patrick Ball, a data scientist and executive director at the Human Rights Data Analysis Group, reviewed the NSA’s technical methodology and described it to Ars Technica as “ridiculously optimistic” and “completely bulls–t.” He argued that the way SKYNET’s training algorithm was set up—with positive and negative training examples defined by the NSA itself—renders the results “scientifically unsound.” In Ball’s assessment, the program’s design all but guarantees that innocent people can be flagged as suspects, simply for having communication patterns the computer finds “interesting.”

Drones, Data, and Dubious Definitions

Numbers surrounding SKYNET grow even more sobering in context. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, cited in both Ars Technica’s report and The Intercept’s documents, estimated that between 2,500 and 4,000 people have died in U.S. drone strikes in Pakistan since 2004. Most were labeled “extremists” by American authorities, but as mentioned in the Benton Institute’s coverage, those lists may have been shaped by the SKYNET algorithm’s questionable classifications. Reviewing one of the leaked NSA slide decks, Ars Technica observed that the system may have been in the works as far back as 2007—plenty of time for its unproven digital methods to influence targeting records.

This prompts a series of uncomfortable questions. How much trust should we place in “black box” technologies for matters of life and death, especially when even algorithm experts balk at the lack of rigor? And at what point does our belief in technological omniscience blind us to its all-too-human bugs and biases?

When Science Fiction Becomes Bureaucratic Routine

There’s a peculiar irony in the U.S. naming its predictive surveillance after Skynet, the same fictional doomsday machine whose “kill-all-the-humans” logic was famously questioned by movie heroes and computer scientists alike. In one scene described by Ars Technica, the line between Hollywood and history feels especially thin—a government program using self-reflective code to identify threats, despite overwhelming doubts from those skilled in data science.

Earlier in their coverage, Ars Technica notes that expert objections like Ball’s haven’t noticeably slowed the momentum behind SKYNET or similar programs. Bureaucratic machinery, once set in motion, proves stubbornly difficult to halt—particularly when it hides behind the opaque authority of machine learning models. In the translation from sci-fi metaphor to spreadsheet reality, has it become easier to trust silent algorithms with decisions too weighty for any human, or have we simply shifted the blame from faceless committees to faceless code?

Reflection: The Algorithmic Ghost-in-the-Machine

So here we sit, at the intersection of old-school cloak-and-dagger and new-school code, watching high-stakes snap judgments rendered by rows of silent, blinking servers. When database quirks and pattern-matching slipups have potential body counts, what exactly does “error” mean, and who bears responsibility? As the Benton Institute’s summary and its underlying sources collectively document, this isn’t the machine apocalypse of science fiction—just the same old human fallibility, clad in a futuristic name and amplified by the scale of modern surveillance.

Maybe the real cautionary tale isn’t that artificial intelligence goes rogue, but that the ordinary, garden-variety bureaucracy finds new, more efficient ways to outpace its own capacity for oversight. Reassuring? Maybe not. But then again, has Skynet ever really been reassuring?