There’s something inherently delightful about a scientific stunt that is, by all accounts, completely impractical. Case in point: the physicists at Loughborough University have etched a platinum violin—thinner than a human hair and too tiny for even a dust mite’s chamber orchestra—onto a microchip. Not so much a feat of musical engineering as a sly wink at the well-worn phrase “playing the world’s smallest violin,” this miniature masterpiece lands somewhere between high-precision science and gentle mockery of human melodrama. It’s equal parts technical flex and meme culture homage.

Smaller Than Drama, Smaller Than Dust

When you hear that a scientific team has built the “world’s smallest violin,” it’s perfectly reasonable to expect a tiny, delicate thing. But according to UPI, this creation measures just 35 microns long and 13 microns wide—significantly smaller than even the finest tip of human hair, which ranges from 17 to 180 microns. That means a tardigrade, the plucky “water bear” of the microscopic realm, would tower over it. A violin you can only spot with a powerful digital microscope isn’t just tiny—it’s bordering on conceptual art.

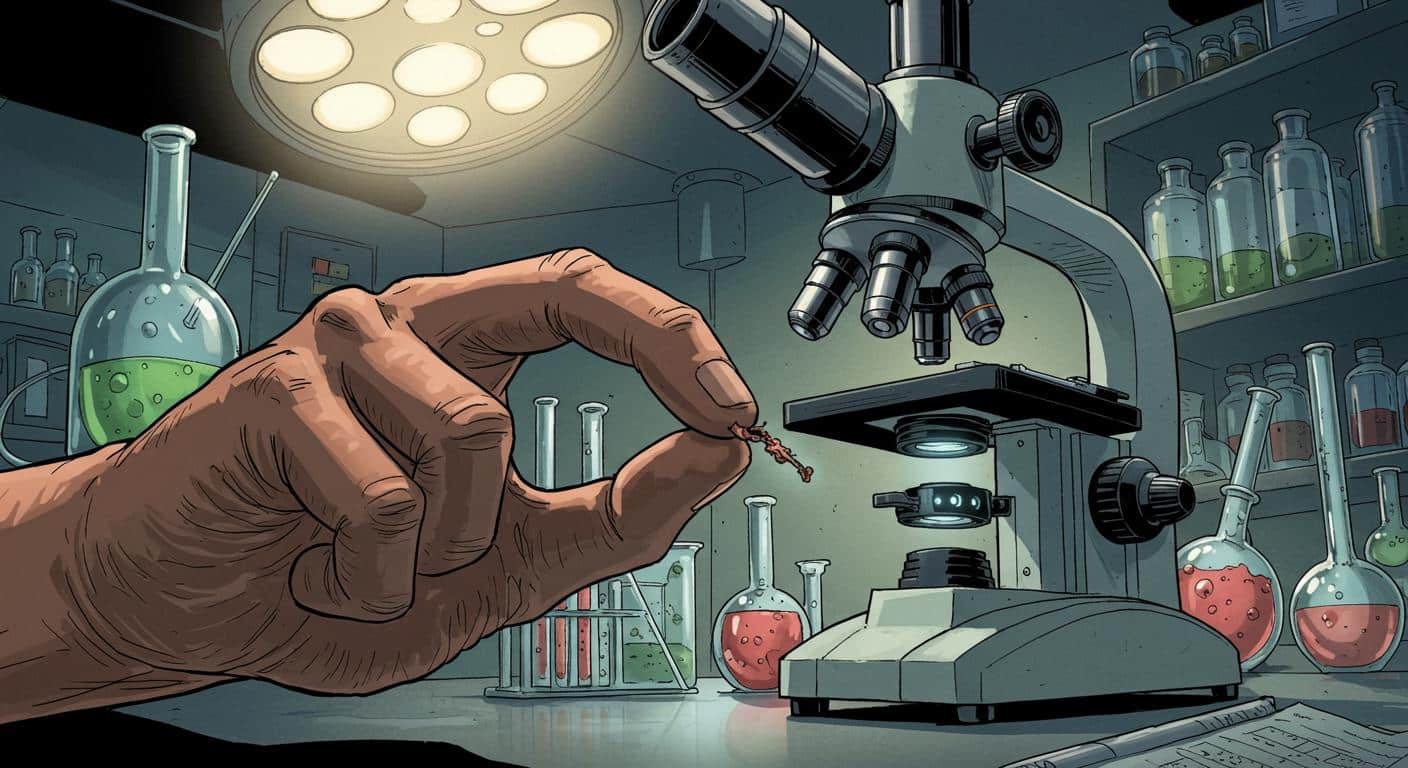

Visually, the instrument amounts to a platinum silhouette, perched atop a chip, looking for all the world like a stray speck of dust. Playability is beside the point: as New Atlas observes, there’s no chance to rosin up this bow—there isn’t even a bow to begin with. Musicians in search of avant-garde performances will have to keep waiting, though there’s a distinctly whimsical appeal to the idea of a silent symphony played out at a scale smaller than pollen.

The process to bring this to life is, in its way, an exquisite piece of theater. Both TechEBlog and designboom outline the meticulous routine: starting with a polymer-coated chip nestled inside a glovebox (dust being a mortal enemy at this scale), the team used a device known as the NanoFrazor. This nano-sculpting instrument carves patterns with a thermally heated tip guided by software instructions; think of it as mural painting, but the “wall” is one-millionth of a meter and the paintbrush could pass for an electron. After the carving, the void-shaped violin was filled with platinum, and a rinse in acetone revealed the finished image. A mere three hours for the operation—though, by the team’s own admission, it took months of trial and error to get everything just right. Dr. Naëmi Leo and Dr. Arthur Coveney, along with Professor Kelly Morrison, stewarded the effort, each name proof that this was no solo act.

More Than a Gimmick—A Trojan Horse for Nanotech

The whimsical exterior hides serious intent. As clarified by UPI and further emphasized in designboom, the violin wasn’t conceived as an art object but as a proof of concept for a new nanolithography system—technology finely tuned to “write” and manipulate structures at the nanoscale, allowing researchers to experiment and push the boundaries of the very small. The phrase “smallest violin” may be playful marketing, but it’s also a practical way to convey just how staggeringly precise these tools are—numbers like “microns” and “nanometers” tend to glaze the eyes without a little real-world context.

The Loughborough team reports that their system is currently fueling two initial research projects: one aims to find alternatives to magnetic data storage, while another investigates using heat for faster, more energy-efficient information processing. The ability to sculpt structures at this scale could have ripple effects, making future computing devices smaller, more powerful, and less power-hungry. Professor Morrison explained, in remarks cited across several outlets, that “a lot of what we’ve learned in the process has actually laid the groundwork for the research we’re now undertaking,” adding that their system lets them probe how materials behave under light, magnetism, and electricity. In other words, today’s meme is tomorrow’s breakthrough, provided the science holds up under scrutiny.

Even the practicalities of the build carry larger implications: constructing anything at this scale is like trying to build a sandcastle on the head of a pin in a windstorm. As both designboom and TechEBlog note, working in a sealed, meticulously controlled environment is essential, since the errant gust of a sneeze—or, more likely, a stray skin cell—could obliterate hours of work.

Not Playable, But Playful

Of course, it’s the cultural resonance of the world’s smallest violin that will likely linger beyond the specifics of nanotech. The phrase itself—the universal hand gesture, the mock sympathy—has now gained a literal avatar. Is it the apotheosis of meme-as-science, or simply a way for researchers to keep things light in the rarefied air of cutting-edge physics? One suspects it’s both. If progress sometimes stirs up anxiety about the ever-shrinking gadgets populating our lives, there’s a certain comfort in the fact that the people driving innovation can appreciate irony—and are willing to leave a platinum Easter egg for the rest of us.

In context, this nano-fiddle emerges not just as fodder for cocktail conversation, but as a case study in how playfulness and rigor can coexist. The field of science is littered with “test objects” that become unforgettable—the wooden duck in early wind tunnels, the teapot in computer graphics, and now, the silent violin playing atop a strand of hair. Why does the miniature capture so much attention? Would the public be as enthralled if the scientists simply announced faster, greener chips with no accompanying visual metaphor? Maybe some things really do need a touch of theater.

The Sound of Science

At the end of the day, the true value isn’t in the object itself, but in the possibilities it signals. Nanolithography, deployed with this level of finesse, has a shot at transforming our tech landscape. Does the world’s tiniest violin actually strike up the world’s tiniest sad song? For the time being, that’s an open question—perhaps best considered while peering, squinting, into a microscope.

If nothing else, it’s proof: sometimes, to show what’s possible, you have to build something gloriously unnecessary. And sometimes, the points go to those who manage to do so with just the right amount of mischief.