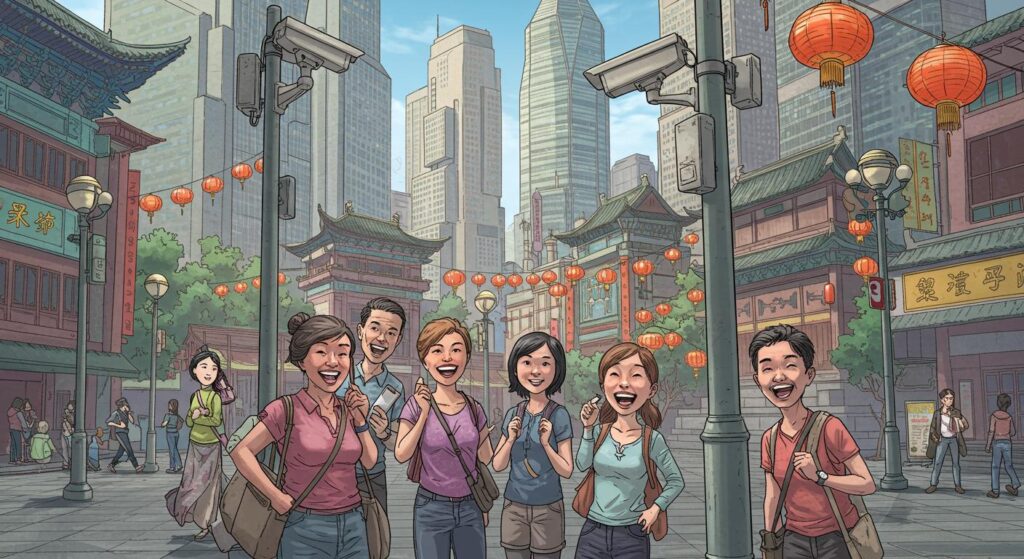

If you’ve ever attempted to scroll through your favorite social media feed only to be ambushed by an avalanche of ads, suggested content, and relentless invitations to “discover” brands you never actually wanted to discover, you might have nodded along to Cory Doctorow’s now-popular term: “enshittification.” The word neatly captures the slow but steady mutation of beloved online platforms into joyless, ad-stuffed husks. But according to reporting from Ars Technica, Meta wants you—and a federal judge—to know that enshittification is more of a feeling than a legally actionable offense.

Meta’s Response: Ads as Feature, Not Flaw

After the Federal Trade Commission wrapped up arguments in its monopoly case, Meta moved to end the trial early. In legal filings described by Ars Technica, Meta asserts that the FTC failed to demonstrate that Meta possesses monopoly power or that its platforms have experienced a decline in overall quality. The company’s motion for judgment states that “the FTC has no proof that Meta has monopoly power,” and that the court should therefore rule in Meta’s favor and dismiss the case.

An interesting centerpiece of Meta’s argument, as detailed in the outlet’s reporting, is that there’s no solid evidence that a heavier ad load on its platforms harms users. Meta points out that the FTC hasn’t defined what constitutes an excessive number of ads, much less shown that Meta displays more ads than a competitive market would support. Furthermore, Meta claims users actually appreciate ads—at least, those who engage with them seem to be shown more, which the company frames as a sign of smart, responsive algorithmic tailoring rather than enshittification.

Meta’s motion, as cited by Ars Technica, even goes so far as to question the premise of the FTC’s entire case, observing that antitrust history doesn’t contain any instances where a monopoly was found solely on the grounds of alleged product quality decline. The company writes, “Meta knows of no case finding monopoly power based solely on a claimed degradation in product quality, and the FTC has cited none.”

Is “Enshittification” a Legal Standard—Or Just a Grumble?

Gathering up the arguments as outlined by Ars Technica, Meta repeatedly returns to the supposed lack of proof: no compelling evidence that “ad load, privacy, integrity, and features” of its platforms have degraded over time, and no basis for claims that its acquisition of Instagram or WhatsApp snuffed out potential competition in a way that hurt users. The article notes that, according to Meta, Instagram was held together with “duct tape,” at high risk for spam, and likely stood to benefit from Meta’s resources. Indeed, the testimony of Instagram’s co-founder Kevin Systrom (as cited in the outlet) describes the pre-acquisition app as “pretty broken and duct-taped.”

Internal emails in which Mark Zuckerberg discussed the prospect of buying Instagram to eliminate it as a competitor, previously described as potential “smoking gun” evidence, are brushed aside by Meta as irrelevant legal relics. Meta’s legal counsel contends, according to Ars Technica’s summary, that what truly matters is the outcome: Instagram, in Meta’s telling, was transformed from a struggling upstart into a success story. The company refers to these improvements as a “consumer-welfare bonanza.” Whether your personal feed feels like a bonanza may hinge on your tolerance for sponsored posts and suggested content, but that’s apparently beside the point, at least in a courtroom.

Turning to WhatsApp, Meta also disputes any assertion that it acquired the app with the secret intention of snuffing out a rival or heading off a competitive threat from Google. Ars Technica documents that, in testimony, WhatsApp’s founders stated they had no intention of becoming a social network and preferred to keep the platform focused on messaging—suggesting that its staying “clean” was an intentional design choice, not collateral damage from a Meta buyout.

Defining Harm: Monopoly or Market Evolution?

The boundaries of the case itself hover over some classic internet territory: When a product gets steadily less user-friendly and more optimized for monetization, does that qualify as legal harm? According to Ars Technica’s review of court records and arguments, Meta claims it’s up to the FTC to show that user experience has declined in a meaningful, measurable way, and that simply having a lot of users isn’t proof that people are captive to a monopoly. The company also maintains that, if users truly disliked the direction of its platforms, they would have departed for competing services, underscoring the supposed vibrancy of the current market.

Yet, as documented by the outlet, the FTC frames Meta’s hold over the “personal social networking services” market as neither fiction nor mere market mood swings. Instead, the agency argues that Meta’s strategy has been to foreclose competition, consolidating control by acquiring promising upstarts before they could grow into true rivals. Notably, Ars Technica highlights that the FTC even rejected a $1 billion settlement offer from Meta, aiming much higher—possibly up to $30 billion—in hopes of forcing dramatic remedies such as spinning off Instagram and WhatsApp.

Crucially, the trial’s fate may depend on whether Judge James Boasberg accepts Meta’s view that TikTok is a true rival, thus framing the relevant market broadly enough to weaken the government’s antitrust arguments. If the FTC’s narrower definition of the market prevails, however, Meta’s position becomes more precarious.

Can You Sue for Ruining the Vibe?

Meta’s response to the charge of enshittification is, at its core, a challenge: Is the creeping over-optimization of digital platforms simply the “way things are,” or should the law recognize a difference between necessary evolution and qualitative rot? The practical reality, as conveyed by Ars Technica, is that courts require detailed evidence of user harm, not just broad dissatisfaction.

So when Meta says there’s “nothing but speculation” behind claims that it choked off competition or made users’ experiences worse, perhaps it’s not just being evasive—it’s drawing a line between communal grumbling and legally defined harm. Until antitrust law can put a specific number on how many pop-up ads or “suggested for you” slideshows tip the balance from innovation to enshittification, the rest of us will just have to keep scrolling.

Or maybe, just maybe, we’ll finally locate that elusive “exit” button everyone keeps insisting is out there.