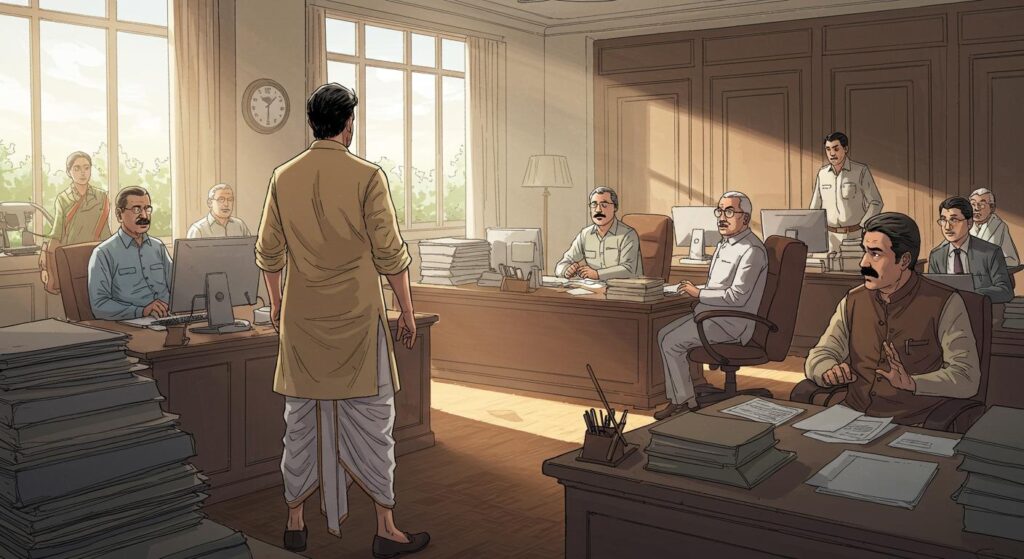

It’s not every day that a municipality tries to dictate what goes on your dinner plate—at least, not with the flair of a holiday decree. But in the city of Kalyan, just outside Mumbai, that’s exactly what happened this August 15th. According to Muslim Mirror, the Kalyan Dombivli Municipal Corporation (KDMC) ordered all butcher shops and slaughterhouses shuttered for a full 24 hours in honor of India’s Independence Day. Vendors of everything from chicken to sheep to “large animals” (a descriptor that might conjure up unwieldy livestock but, for practical purposes, means goats, sheep, and the like) were told to close at the stroke of midnight, reopening only when the holiday had run its course.

No Mutton for My Martyrdom

The Economic Times reports that this ban isn’t new for the city. KDMC’s deputy commissioner for licences, Kanchan Gaikwad, said the restriction has been issued every year since 1988 under a civic resolution, with the official stance that this is meant to “maintain public order” and observe national occasions “respectfully.” Under the Maharashtra Municipal Corporation Act, anyone caught violating the order—with a surreptitious mutton chop or otherwise—can face legal action.

Political reactions, however, have been anything but routine. The Economic Times details how NCP-SP MLA Jitendra Awhad criticized the ban and announced, in a pointed bit of protest, his intention to host a “mutton party” on Independence Day. “On the day we got freedom, you are taking away our freedom to eat what we want,” Awhad declared to PTI, channeling a certain carnivorous patriotism. Shiv Sena (UBT) leader Aaditya Thackeray also condemned the order, demanding the KDMC commissioner’s suspension, as the outlet describes. Both leaders questioned the legitimacy and rationale of telling residents what they can eat on a holiday fundamentally about individual liberty.

Suresh Mhatre, Bhiwandi MP and NCP-SP leader, joined the chorus, emphasizing to reporters (in details highlighted by the Economic Times) that local food habits are intricately tied to traditions, particularly in coastal communities such as the Agri Koli, who integrate fish and meat into their diets as a matter of custom. “Food habits are shaped by customs prevalent in different parts of the state. The ban on meat sale is incomprehensible,” Mhatre said. In the same report, Awhad questioned, “Who are you to decide what people will eat and when?” suggesting that dietary preferences are, and should be, a matter of personal freedom.

“What Will Happen If You Miss Meat for One Day?”

Meanwhile, others see the whole debate as overcooked. As reported by Muslim Mirror, Kalyan (West) MLA Vishwanath Bhoir, representing the ruling Shiv Sena, defended the ban by asking, “What will happen if one doesn’t eat meat for one day?” In the Economic Times article, Bhoir also argued that the majority weren’t opposing the order, brushing off opposition as habitual criticizers.

A broader perspective emerges from Hindustan Times, which notes that similar bans were issued by other municipal bodies in Maharashtra and Hyderabad, with some closures extending to August 16 for Janmashtami. Political reactions didn’t fall neatly along party lines. Deputy Chief Minister and NCP leader Ajit Pawar questioned the logic, saying a ban might make sense for religious observances like Mahavir Jayanti but seemed uncalled for on Independence Day itself.

Opposition figures from the MNS and Congress accused local leaders of imposing vegetarianism to distract from more urgent issues like potholes or traffic jams. Congress leader Vijay Wadettiwar called the move a “ploy to distract from real problems,” as cited by Hindustan Times, while Shiv Sena (UBT) leader Aaditya Thackeray demanded a halt to “entering our homes” and policing food choices, pointing out that even some Hindu communities offer non-vegetarian dishes during festivals. AIMIM chief Asaduddin Owaisi also publicly criticized Hyderabad’s municipal ban, labeling it “callous and unconstitutional,” and raised concerns over violations of liberty, privacy, livelihood, and nutrition.

BJP representatives, according to Hindustan Times, pointed to historical precedent, stating that similar bans were enacted under past Congress and Maha Vikas Aghadi administrations—suggesting that critics weren’t opposed to such policies until now.

Ritual, Routine, or Red Herring?

Throughout all this, the reasoning from civic bodies continues to circle back to a desire for “public order” and “respectful celebration.” The Economic Times notes that local officials insist it’s simply a longstanding observance, not a targeted move against any group or dietary preference. Nonetheless, critics, as documented by Hindustan Times, argue that these bans are less about national unity and more about performative governance or ideological messaging. Food choices in India are inherently political, cultural, and—on days like August 15—symbolic.

For those living in Kalyan or other affected cities, the annual holiday presents an unlikely thought experiment: What does it mean to celebrate freedom if civic authorities are busy dictating dinner? And does ritual observance trump personal and cultural autonomy?

A Ban by Any Other Name

When a city’s Independence Day commemoration doubles as a day of closed butcher shops and heated debates, one wonders what’s really at stake. As the Economic Times and Muslim Mirror both highlight, what began as a “routine order” now sparks fresh questions about how a society balances tradition, governance, and the granular details of daily life—like what’s on your dinner plate. Are bans like this an act of genuine public respect, a bureaucratic habit, or simply something stranger?

If nothing else, it’s a reminder that even the most routine rules can serve up a full helping of controversy—especially when they come between a community and its customary meals. For politicians like Jitendra Awhad, a mutton party is both protest and celebration—a fitting, if slightly cheeky, tribute to the spirit of independence.