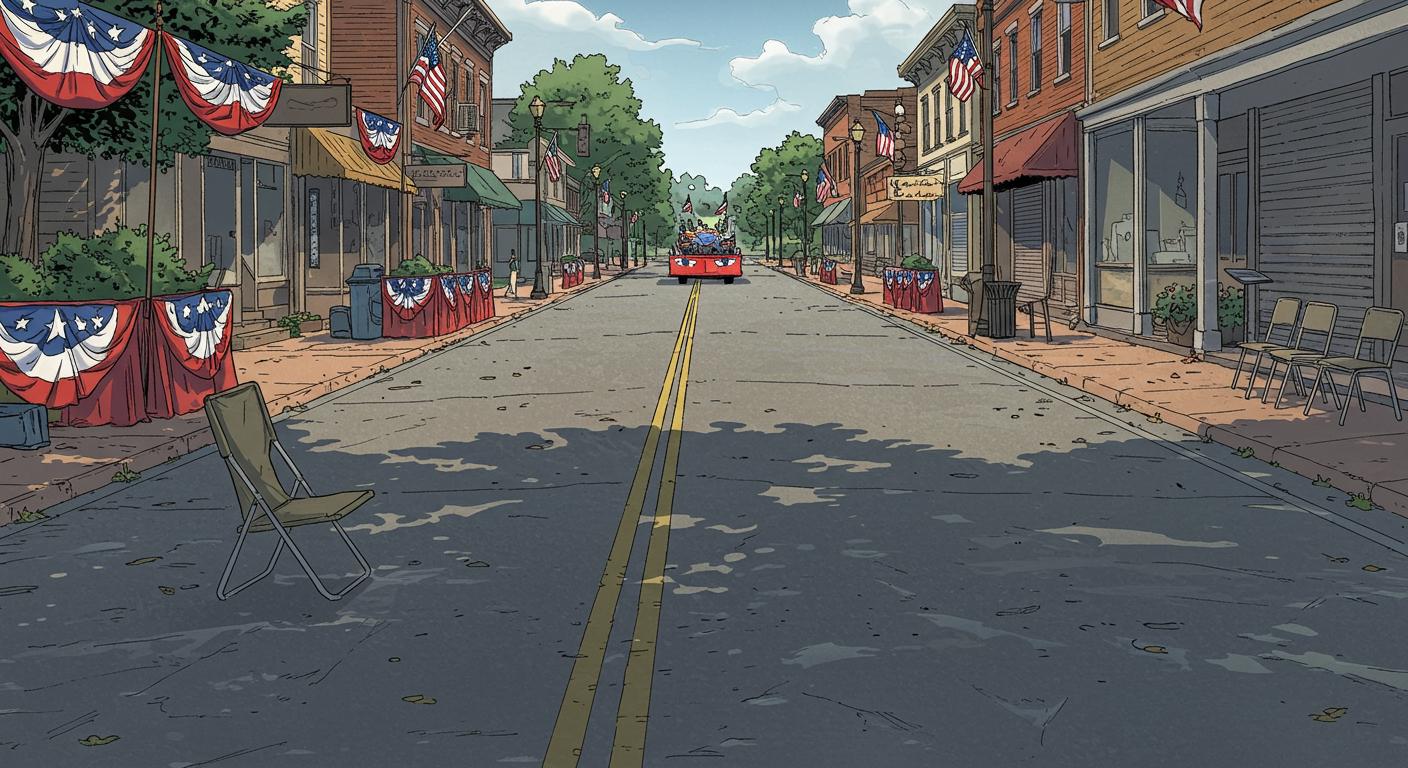

There’s a kind of comfort in the predictability of an old-fashioned Fourth of July parade: kids darting after candy, humid air heavy with the scent of grilled hotdogs, the distant crackle of a community band bravely attempting Sousa. But this year, residents of Whitemarsh Township, Pennsylvania, will have to make do without the traditional mile-long procession that’s marked the holiday for decades. As reported by CBS Philadelphia, the township’s board, after deliberation with police and emergency management, has called the whole thing off, citing “unnecessary risk to the community.”

Safety Concerns on Parade

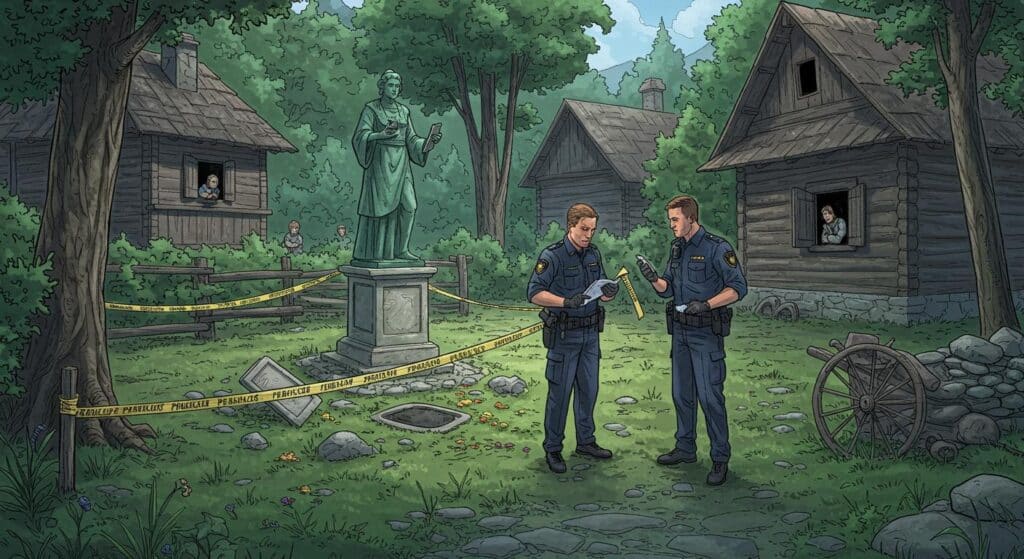

According to CBS Philadelphia, the official explanation isn’t ambiguous, nor is it rooted in any specific threat—township officials made clear there’s no known villain lurking around the marshes of Montgomery County. Instead, it’s a broader anxiety, grounded in the very modern calculus of public event risk management. Township manager Craig McAnally, speaking at a recent board meeting, summed it up: “We can’t safely have a parade and have everyone feel safe, if we don’t do everything that we’re looking at for this parade to eliminate any kind of vehicle incursions or anything like that.” The potential for a vehicle-ramming attack weighed heavily on the decision, particularly in light of incidents at public gatherings in other cities, such as the New Year’s Day tragedy in New Orleans. As described in 6abc’s report, the dangers considered also included attacks like those seen in Vancouver and a shooting during a parade in Illinois.

Officials reviewed the logistics, evaluating “the personnel and resources it would take to secure not only the parade route…but also the surrounding streets,” a point echoed in a statement covered by 94.5 PST. The security upgrades required—such as reinforced barriers—turned out to be either cost-prohibitive or unavailable, since similar protections are already allocated for other towns’ events. Without the ability to guarantee the level of safety now deemed necessary, Whitemarsh’s leaders decided not to take the risk.

Tradition Meets the Modern Mood

Resident reactions captured by 6abc hint at a mix of surprise and resignation. Mara Cook, who attends annually with her family, shared that the community felt blindsided and noted a lack of transparency around the decision’s timing. For a tradition running over seventy years, the news felt especially abrupt. Another local, Tinaudra Foster, offered a more reflective take: “It’s understandable, but you still got to live and enjoy life at the same time.” There’s a muted tension here, a reminder that for some, the risk calculus has quietly but profoundly changed the rituals of public celebration.

Officials made clear through both CBS Philadelphia and 6abc that there is no current, credible threat to the Whitemarsh parade. Yet as Police Chief Christopher Ward pointed out during the township meeting, other cities that experienced attacks didn’t have advance warning either. The multiplatform coverage reveals a common thread—the decision is grounded more in the evolving perception of danger and the costs of preventative measures than any direct intelligence.

The Cost of Feeling Safe

Despite repeated inquiries, township leaders have not disclosed the precise cost that would be required to implement these modern security measures. Ward noted, according to 6abc, that “it can be quite significant compared to what we’ve been doing at this point.” The absence of a firm figure is oddly telling—the price of concrete barriers becoming a determining factor in whether a community comes together or stays home. It’s all a bit dryly ironic: an Independence Day parade, sidelined by the escalating cost of guaranteeing freedom from harm.

Community or Calculus?

One has to wonder, as highlighted in the 94.5 PST report, how many other towns are watching Whitemarsh—and quietly reconsidering their own plans. The “unnecessary risk” threshold, it seems, is now shaped by both local appetite for caution and municipal budgets grappling with the realities of upgraded security needs. Are we seeing the slow transformation of communal celebrations, gradually replaced by smaller, tightly controlled, or even virtual gatherings? Or is Whitemarsh, as some might wager, simply the exception in a nation still drawn to the quirky comfort of parades?

An old spirit of resilience underlies all this—a spirit that once propelled marching bands and fire trucks down main streets regardless of heat or humidity. Yet, as Board of Supervisors Chair Jacy Toll acknowledged to CBS Philadelphia, “we wish there were a better choice. In this case, we don’t believe there is.” Sometimes the modern calculus of risk and cost simply overwhelms even the oldest of civic rituals.

So, is this an excess of caution, or just prudent realism in an unpredictable era? Maybe it depends on whether you see an empty parade route as a temporary pause, or a new kind of tradition—one where safety, rather than spectacle, leads the procession.