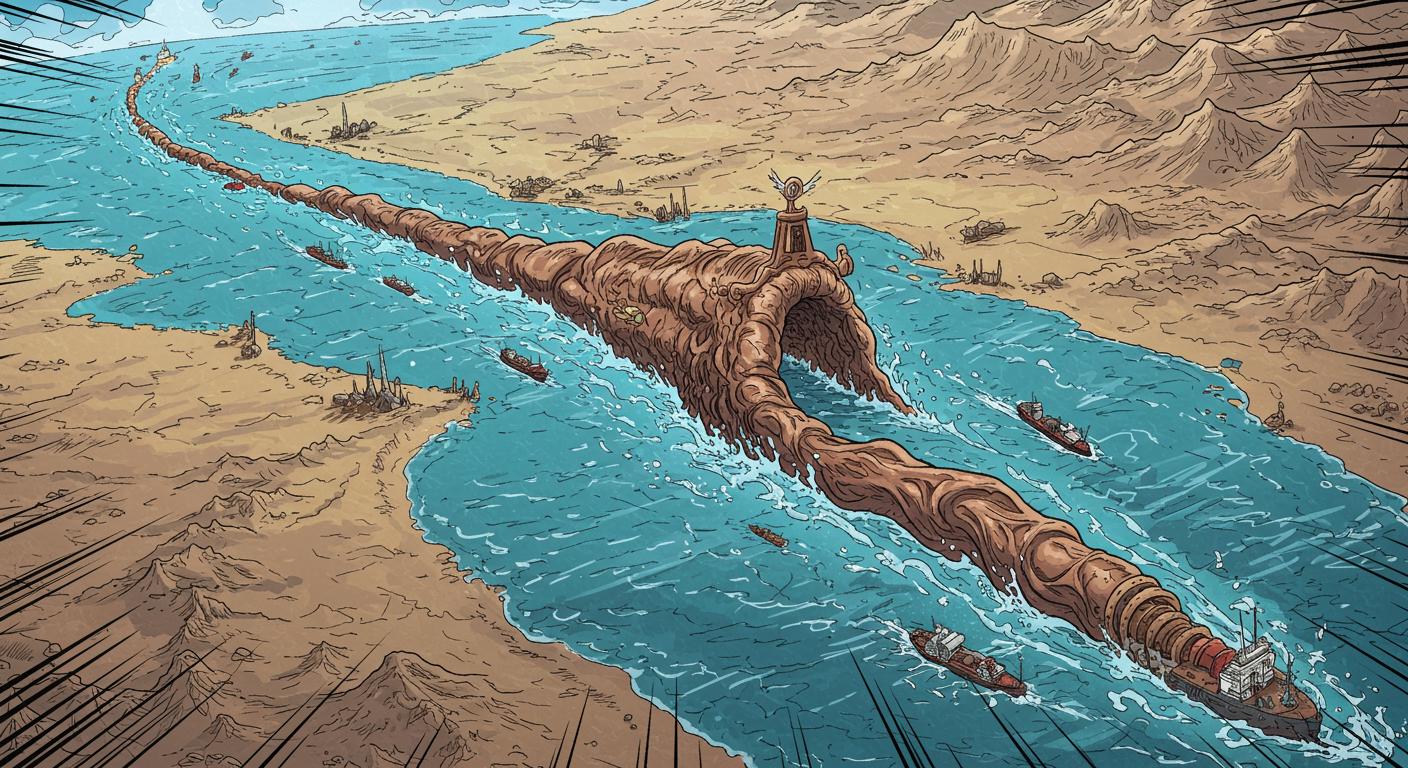

There are certain metaphors so vivid that you can’t help but hear their echoes later in the shower—oddly enough, the recently unleashed “pyloric sphincter” analogy for the Strait of Hormuz is one of them. It’s the sort of anatomical-meets-geopolitical comparison that delights the librarian half of my brain and mildly alarms the public policy side. Today, let’s poke around this exceedingly narrow waterway and its sudden role as the hapless gatekeeper for roughly a fifth of the world’s oil. If global commerce really does have a digestive tract, then you have to wonder: what does an attack of geopolitical indigestion look like?

A Choke Point With Gut Instincts

As the Guardian explains, the Strait of Hormuz is a mere 33 kilometers wide at its tightest section—an oceanic bottleneck by any definition. Wedged between Oman and Iran, this critical passage ferries about 20 million barrels of oil every day, data from analytics firm Vortexa shows, channeling between one-fifth and one-quarter of global oil consumption through two shipping lanes that are each just 3km across. When you realize the planet’s energy supply is funneled through narrows smaller than the length of an airport runway, the digestive metaphor feels almost too apt—one ill-placed mine, and global “nutrients” aren’t making it past the duodenum.

Most major OPEC nations—Saudi Arabia, Iran, the UAE, Kuwait, and Iraq—are forced to contend with this bottleneck, exporting nearly all their crude through the strait, primarily destined for Asian markets. The Guardian details how the US Fifth Fleet, based out of Bahrain, is tasked specifically with policing this watery artery—a 21st-century manifestation of “keeping things moving” if ever there was one.

When Blockage Is Both Threat and Symptom

Described in the Guardian’s reporting, recent tensions have ratcheted up after US airstrikes targeted three Iranian nuclear sites. With Iran’s parliament quickly approving (at least on paper) a measure to close the Strait of Hormuz, all eyes are on whether this oft-threatened maneuver will leap from bluster to reality. In a detail highlighted by Iran’s Press TV and cited by the Guardian, the final decision rests with Iran’s senior leadership, not lawmakers alone—a nuance likely lost in the noise.

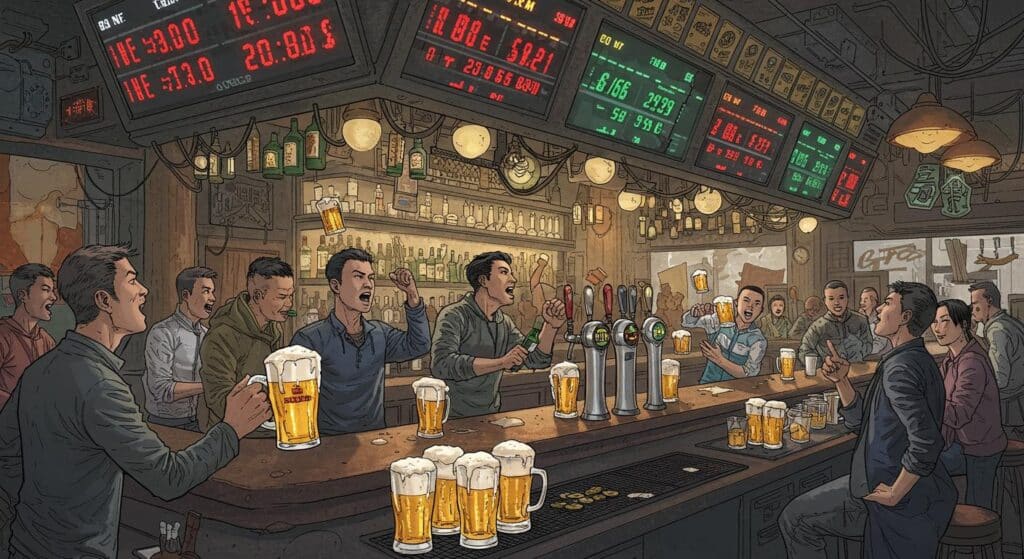

The possibility of closing the strait is, as ever, both a threat and a double-edged sword. On the one hand, as US Secretary of State Marco Rubio told Fox News in statements referenced by the Guardian, shutting Hormuz would create a near-instant spike in oil prices and set off inflationary shockwaves, particularly in the US and China—the latter reportedly receives almost 90% of Iran’s (already-sanctioned) oil exports by that route. Rubio’s description of a closure as “economic suicide” for Iran isn’t hyperbole: the passage acts as the gateway for Iranian oil, too, meaning blockade would inflict self-harm of the dramatic variety. Whether Iranian policymakers are seeking diplomatic leverage or signaling resolve for domestic eyes remains a bit of an open riddle.

Meanwhile, Nick Childs from the International Institute for Strategic Studies, quoted in the Guardian, summarizes the military calculation: Iran’s inventory of thousands of sea mines—such as the rocket-firing EM-52, acquired from China—could create genuine havoc, especially if deployed rapidly by Iran’s mix of Russian-made Kilo-class submarines and the smaller, locally-built Ghadir types. The military script isn’t entirely hypothetical; the article recalls how USS Tripoli and USS Princeton ran into Iraqi mines during the 1991 Gulf War, demonstrating that even advanced navies can take a bruising navigating these treacherous waters.

Satellite tracking and shipping reports described by the Guardian indicate that some supertankers have already begun quietly U-turning away from the strait after the recent US strikes, adding a practical reminder that for traders and insurance companies, preparedness for maritime heartburn is not optional.

Digestion… With a Cost

Closing the Strait of Hormuz, as observers cited by the Guardian emphasize, carries serious risks beyond mere brinkmanship. Any such move would almost certainly escalate the conflict, potentially drawing in Gulf states compelled to safeguard their own oil flows and revenues. Relations in the region already run hot; adding a blockade could easily tip the balance further towards open hostilities, particularly with states that have been outspoken critics of recent developments.

The multi-billion-dollar question: are Iran’s threats a rational bluff, an exercise in nationalistic signaling, or a desperate gambit reminiscent of someone slamming shut their own kitchen door and blaming the neighbors for a missed meal? Does anyone in Tehran’s corridors genuinely believe engineering a self-induced gallbladder attack is a winning strategy, or is it simply a way to keep adversaries guessing (and markets jittering)?

Is There a Cure for Global Heartburn?

Stepping back, the image of the Strait of Hormuz as the world’s most consequential sphincter remains awkwardly fitting—and, if you’ve ever had an upset stomach, just a little funny. As maritime analysts and diplomats alike remind us, centuries of grand strategy can end up hinged on a few unpredictable kilometers of salty water, where too much pressure spells disaster for all involved.

Would alternate pipelines, new routes, or renewable energy lessen our collective dependence on such anatomical choke points? Or is humanity doomed to play yet another round of “Will They, Won’t They” with each flareup in the Gulf? And for those on the frontlines, who gets to explain strategic mine-laying to the global underwriters—do they start with an anatomy lesson or a flowchart?

For now, the world watches, stomach twisting, to see whether this all-too-human organ of global trade spasms shut—or if, like many a persistent digestive problem, it grumbles on without quite grinding to a halt.