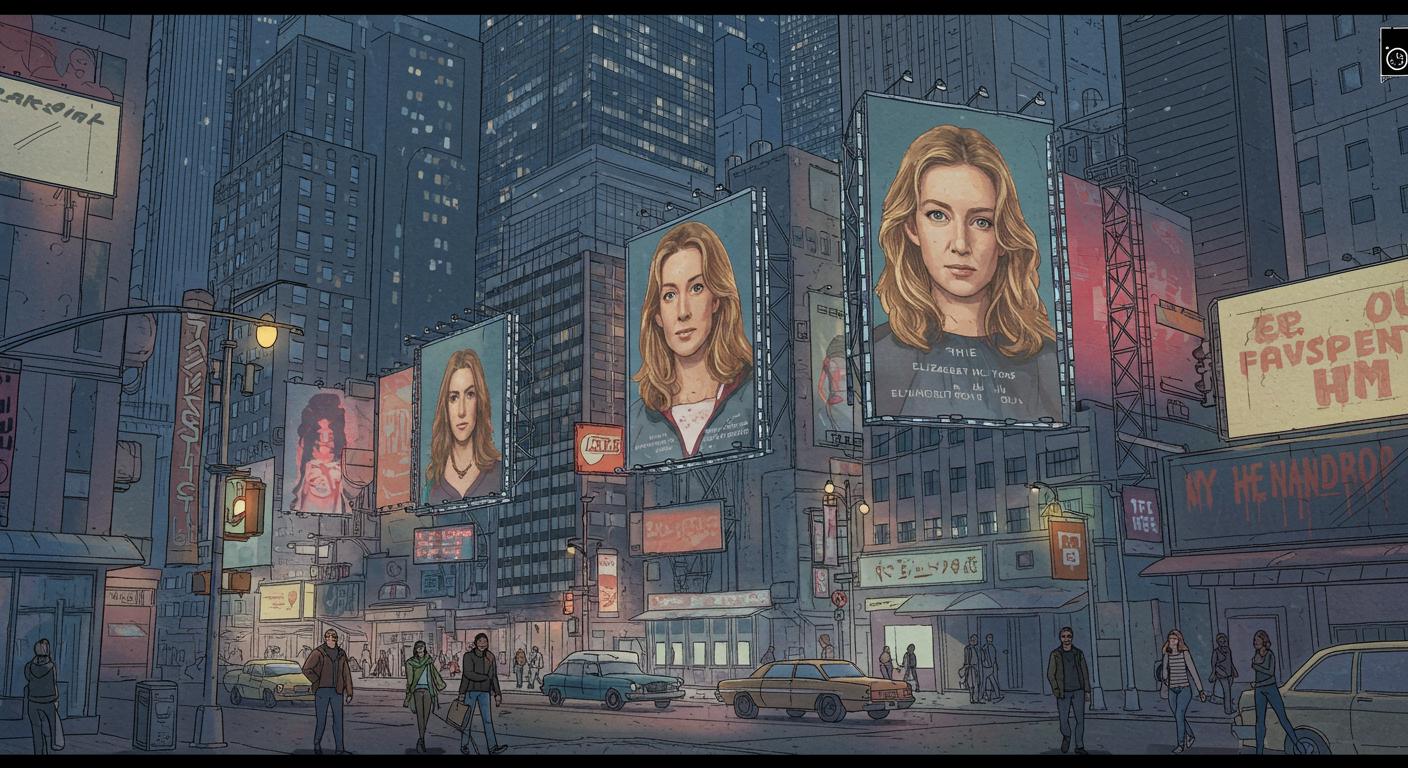

It’s not every day that you spot a giant, high-definition portrait of a recently convicted tech CEO gazing out from Times Square or a Florida highway. Yet, as detailed in NewsNation’s report, Elizabeth Holmes—the ever-controversial founder of Theranos whose spectacular rise and public downfall have already inspired books, documentaries, and a podcast or three—has reappeared in the public sphere, or at least her face has.

Curiously, Holmes is neither masterminding nor even actively participating in this grand rebranding, since she’s currently serving time at a Texas prison camp. Instead, the spectacle belongs to Ryan “Egypt” El-Hosseiny, a Miami entrepreneur whose campaign to revive both Holmes’s reputation and Theranos’s mythology is, apparently, best communicated via sensorially dominating signage.

Advertising Redemption…or Revisionism?

NewsNation highlights that El-Hosseiny has plastered larger-than-life images of Holmes—sometimes accompanied by himself—across billboards in California, Florida, and the ever-theatrical Times Square. Not content with just spectacle, El-Hosseiny has made some eye-catching claims: he says he has relaunched Theranos in 2025, and brands himself and Holmes as “the inventors” on select billboards. If nothing else, his marketing strategy is anything but subtle.

Tying into all this is “Just Blood,” a documentary El-Hosseiny is reportedly developing, which he has suggested will offer a fresh look on Holmes and the infamous Theranos saga. The Hollywood Reporter, referenced in the NewsNation piece, notes that the documentary seems to be about reframing Holmes and her shuttered company, though the boundaries between investigative filmmaking, image rehabilitation, and guerilla PR remain somewhat hazy in this context.

Within a single paragraph, NewsNation relays both El-Hosseiny’s public statements and apparent ambitions: the billboards, he says, are part of his larger mission to “free Elizabeth Holmes” and “take on Big Pharma.” By his own account, he has “done his homework” on Theranos and positions himself not as a “sock puppet in the healthcare space” but as a genuine innovator keen to prioritize quality products over profit. In a statement to the Miami New Times, he takes a swipe at critics and previous investigators by declaring, “No one did their homework on Theranos. I did, and I’m here today.”

This invites a certain curiosity—has anyone ever successfully given a tech company a second act using sheer billboard volume? Are we witnessing an elaborate piece of performance art, or just another patch in the historical quilt of American reinvention?

The Lure of the Second Act

As noted in NewsNation’s coverage, Holmes’s original legal entanglement was anything but minor: she was convicted in 2022 for defrauding investors with blood-testing technology that never worked as promised, despite bold claims that it could detect numerous diseases from just a finger-prick’s worth of blood. Her attempt to overturn this conviction found no success earlier this year, with federal appeals court judges ruling against her bid for a new trial.

Yet, through El-Hosseiny’s energetic public campaign—which, to be clear, seems to be moving ahead without Holmes’s direct (or at least, substantiated) involvement—the figure of Holmes is being repositioned. Is this an earnest effort at vindication? An opportunistic chase for public attention? Maybe it’s an ongoing experiment in how long a bold story can outpace the facts.

It’s telling that, in some versions of El-Hosseiny’s narrative, skepticism about Theranos is cast not as reasonable caution, but as a collective failure to recognize visionary innovation. One has to wonder: If scientific consensus, federal court rulings, and diligent reporting didn’t count as “doing the homework,” what new revelations does this marketing blitz expect from us now?

Spectacle, Skepticism, and Reality Checks

Even in a culture accustomed to Silicon Valley comebacks, the billboard campaign feels strange—not merely for its subject, but for its method and timing. As previously reported by NewsNation, these public declarations come at a moment when Holmes no longer has the ability to manage her brand. At the same time, El-Hosseiny’s insistence that he’s singlehandedly corrected the sins of Theranos’s past is, by his own account, a mission grand enough for highway-sized fonts.

The details swirl with a kind of surreal logic only found at the intersection of true crime, tech, and pop culture: the disgraced CEO, the self-styled inventor-cum-filmmaker, the relaunch of a notorious brand, and a public relations battle being staged in glittering high-definition, well outside the usual halls of science or justice.

One can’t help but ask: Has anyone, in the entire history of innovation, ever been convinced by a billboard to revisit a universally discredited idea? Or is this just an extra-large reminder that, when it comes to stories like Theranos, reality is almost always stranger than fiction?

Final Thoughts

What we’re left with is a peculiarly American spectacle, where old scandals are repackaged for new audiences in ever-brighter wrapping. Is this a sincere attempt to right a perceived wrong, or more a case of “if you can’t change the verdict, change the narrative”? The line between earnest reinvention and elaborate revisionism seems as blurry as ever.

Whatever the answer, it’s probably safest to drive cautiously past the next billboard promising a revolution in healthcare. But maybe, just maybe, pause for a second and marvel at the sheer oddity of it all. In the end, the Theranos saga still manages to surprise—and, apparently, to go bigger.