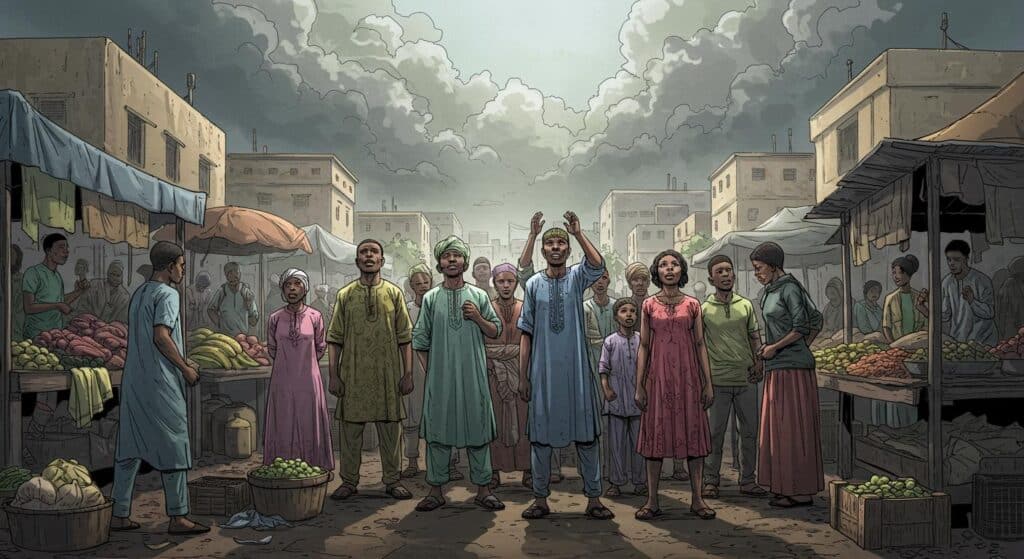

If there were ever doubts that modern technology and human curiosity would eventually join forces in strange new ways, the crowds in Ahmedabad have essentially settled the debate. The Hindustan Times recounts how the site of the Air India Dreamliner crash at BJ Medical College’s hostel has rapidly become something of a pilgrimage—for smartphone-bearing disaster tourists. In a country where aviation disasters of this scale are mercifully rare, it seems the line between commemoration and content-creation is unexpectedly thin.

The Tail as a Backdrop

It’s almost cinematic: people assembling under a scorching 40-degree sun, weaving through police barriers and making their way toward a chaotic tableau centered on the wreckage of a Dreamliner’s tail, which remains stuck fast inside the side of a building. The outlet details how visitors are angling for selfies and group photos as close as 100 meters from the debris, often with the tailfin in crisp focus—a stark and sobering composition, though perhaps not for the reasons intended by its subjects.

Residents from areas well outside Meghani Nagar joined in, including Krunal Panchal, who told the outlet he couldn’t resist seeing the aftermath firsthand after finishing work nearby. Others appeared motivated by the dramatic images they’d seen televised, eager to witness the physical reality for themselves. Descriptions in the Hindustan Times paint a scene not just of individual curiosity, but a sort of communal energy, as families, groups of friends, and even small children crowd in for their glimpse.

While the authorities have cordoned off the worst of the crash, much of the neighborhood remains open to foot traffic. Police posted at multiple control points seemed overwhelmed, attempting (with polite persistence) to move the crowd along but, by their own admission, largely unable to stem the influx—particularly from younger people. One officer remarked that the sheer numbers and the crowd’s composition made the usual enforcement tools impractical.

Meanwhile, building residents found themselves cast as surprise stewards of the city’s hottest—if most unwelcome—tourist destination. As noted by the outlet, Aditya Patani, whose residence offers an unobstructed view of the tailfin, ended up locking his rooftop terrace to prevent strangers from streaming in to secure the optimal vantage point. One wonders if disaster proximity was ever a factor when he picked out his apartment.

No Barrier to Entry—Except a Locked Terrace

“Random person or strangers” was how Patani described the sudden influx on his property. It’s the sort of phrase that might make one nostalgic for the early days of travel photography, when collecting a “souvenir” probably didn’t require negotiating your way past locked doors. The scene as documented blends the surreal and the slightly weary: officers issuing repetitive warnings, hostellers playing amateur sentry, and everywhere the shimmer of recording screens.

The Hindustan Times describes families braving the midday heat and weaving their way to any spot left accessible around the secured debris. For many, recordings and photos seem less about the tragedy itself and more about personal documentation: visual proof of “I was there,” uploaded to the digital ether for immediate validation.

Colliding with the Spectacle

This is, perhaps, where old instincts meet new tools. The urge to witness disaster isn’t a twenty-first century invention, but the rapidity and purposefulness with which we now package tragedy for personal feeds is a peculiar evolution. Rather than collecting stones from a site or swapping war stories, the disaster tourist now aims for a selfie with the tail in the background and, on a good day, maybe a recognizable officer somewhere in the frame for scale.

Earlier in the report, it’s mentioned that for some, even the presence of children didn’t dampen enthusiasm—if anything, it provided a “family outing” element. For the residents suddenly presiding over the parade, it’s a momentary loss of privacy, not to mention a reminder that grief and spectacle often become uncomfortably intertwined.

Retweeting Reality

One officer summed up the predicament to Hindustan Times: it’s not just crowd control, it’s attempting to police the line between public curiosity and respectful distance, with little hope of success amid a sea of outstretched phones. What, exactly, are people seeking—a connection to a historic event, or digital memorabilia that outlasts the headlines?

Perhaps this is just what it looks like for collective mourning—messy, public, and not entirely separate from the compulsion to document everything. Public sites, no matter their significance, are never immune to the intersection of empathy, curiosity, and, sometimes, the faint glow of a social media notification.

It does beg the question: When our disaster souvenirs are instantly shareable, do we process these tragedies differently? Or is this simply another way human beings try to make sense of a world that, at times, veers from the rational straight into the surreal? One summer afternoon in Ahmedabad suggests we still find communal catharsis in the strangest places, just with more megapixels.