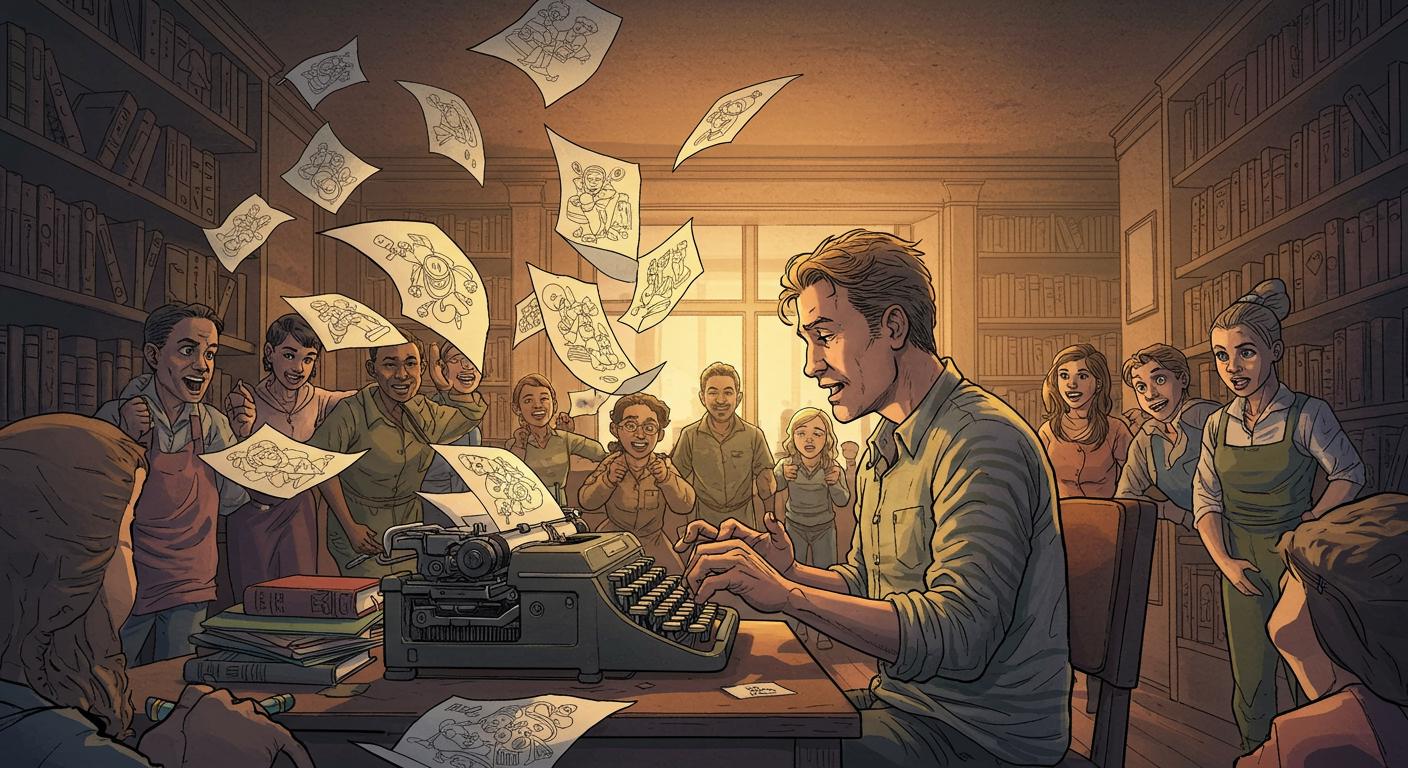

There’s a certain kind of magic to modern anachronism—where technology long rehomed to thrift stores and odd corners becomes the centerpiece, not the punchline, of an experience. So, when I read that Keira Rathbone would be performing live typewriter drawings at Falmouth Library, I didn’t just smile—I had to wonder, does the thunk of a vintage typewriter inside a public library conjure nostalgia, or something more subversive?

Art by the (Space) Bar

BBC News reports that Rathbone, who has practiced typewriter art for over two decades, will stage her event at Falmouth Library on 10 May. She uses a manual typewriter—what she fondly dubs her “time-travelling” writing device—to create live portraits of visitors, a process which typically lasts about ten minutes. Attendees will have the opportunity to leave with a unique image that Rathbone describes as a “piece of work that’s about them.” The library session is set to run from 10:00 BST to 17:00.

Rathbone told BBC Cornwall that her medium isn’t quite painting or drawing as one might expect; instead, she refers to these works as “epictions in type,” “typics,” or “typictions.” Describing how her journey began about 22 years ago, Rathbone explained that she initially approached her typewriter wanting to type but was at a loss for words, so she “just started pressing.” In a detail noted by the outlet, she realized she saw not lines of letters but shapes—corners, textures, possibilities—hidden within the typewriter’s keys. That’s when typed characters, in her view, began to transform into the raw material of visual art.

The Library, Re-Imagined

As documented in the BBC coverage, Rathbone sees her art-making process as a kind of bridge between eras. She described the typewriter as feeling “almost like a time-travelling device,” adding that she loves how it draws the public in—literally and figuratively. The experience, she suggested, doesn’t just capture people in the present but lingers in memory, “stick[ing] in their heads later.” It’s a detail that sets her work apart; each visitor leaves not only with their likeness but with what Rathbone characterizes as “the essence of them, sort of boiled down to minimal characters.”

This notion of essence, as outlined in the BBC article, brings a certain intimacy to the encounter. The library—typically a haven of hushed concentration—is momentarily transformed into a theater of clicks and deliberate, analog creation. It’s not hard to imagine the room alive with the gentle clatter of typebars and the curious energy of onlookers drawn by something both familiar and unexpectedly novel.

The Essence, Boiled Down

When Rathbone describes, in the reportage, how her typewriter artwork takes people back while capturing them in the present, she nudges at something libraries already do quietly well: connecting the threads of past and present, and occasionally making the ordinary strange again. The BBC’s depiction of her work avoids framing it as simple nostalgia; rather, it highlights the awkwardness and honesty of the medium. There’s no digital filter or algorithm tidying things up here—just palpable effort, evidence of time spent, and the willingness to let a found typo become a defining feature of a portrait.

Is it the fascination with visible limits—the way the art is shaped as much by the quirks of the typewriter as by the artist—that keeps us coming back to things like this? Or is it the reassuring tangibility of a machine that makes a mistake you can see and touch, turning imperfection into style?

More Than a Throwback

The BBC also notes that Rathbone’s art does not lean into retro aesthetics for their own sake. Instead, by distilling her subjects into faces and features made from punctuation marks, she offers what might be the ultimate analog remix: identity seen through the grid of @s, slashes, and periods. In a world crowded with frictionless digital images, perhaps the real peculiarity is how captivating manual constraint can be.

So what happens when you let your portrait be spelled out by the mechanics of a bygone device? Maybe it’s just an oddball souvenir. Or maybe you, too, exit as an asterisk in someone else’s weird and wonderful archive—a character in a story still rattling on, one keystroke at a time.

Does that possibility linger with you, too? Or am I just charmed by the echo of old keys in new spaces?