California Park’s Newest Unofficial Resident: One Large Tegu

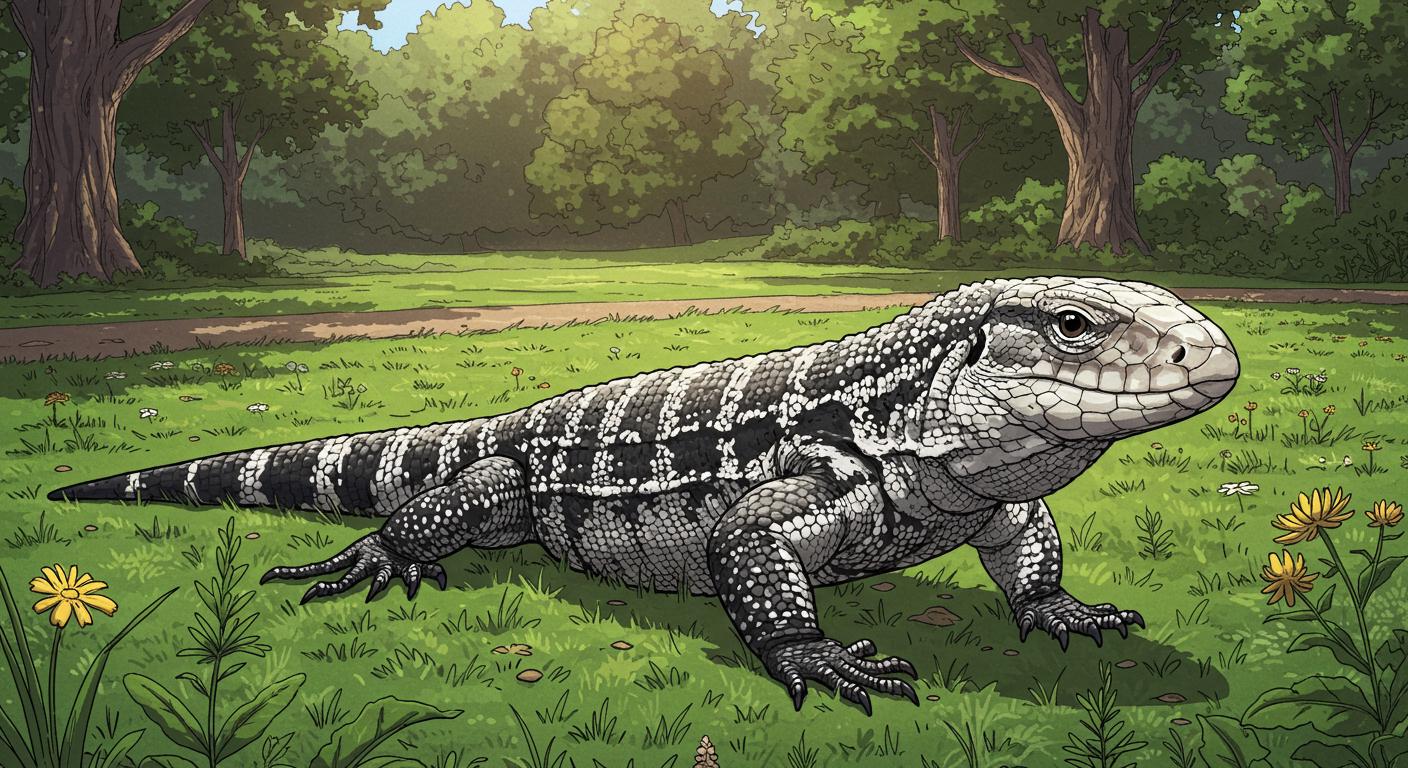

When most people think of wildlife lurking just off a California hiking trail, they imagine the usual suspects—a startled deer, a coyote, or, if your luck is particularly questionable, a rattlesnake. But recently, hikers at Joseph D. Grant County Park in Santa Clara County encountered something that seemed more suited to a subtropical menagerie: a sprawling Argentine black and white tegu lizard, easily the size of an ironing board and marked in a pattern straight out of a natural history museum. As UPI reports, park maintenance staff and rangers coordinated the lizard’s safe capture after it was spotted wandering on the dam at Grant Lake—likely the only time the reservoir has played host to such a reptilian guest.

An Exotic Arrival and a Community on Alert

The initial sighting, according to Hoodline, came from a group of quick-thinking hikers who not only photographed the unusual visitor but promptly notified park staff. Santa Clara County Animal Services and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife were brought in, with authorities confirming to UPI that the tegu was transported safely to a county animal shelter. Social media messages from Santa Clara County Parks, highlighted by KRON4, made clear the department’s mixed feelings: “They’re a popular pet and don’t belong in parks,” staff wrote, calling on the public not to search for or attempt to capture the tegu but to alert rangers instead.

KRON4 also notes the department’s assurance that, while the tegu’s appetite makes it a menace to eggs and small animals, “they are docile so they won’t harm people.” A strange sort of comfort for anyone crossing paths with a four-foot lizard in the grass.

The Invasive Wild Card

For the uninitiated, Argentine black and white tegus are not only imported exotics but, as described in Hoodline, “efficient egg predators”—a title bestowed by University of Florida researchers who’ve tracked tegu populations in the southeastern U.S. Originally native to Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, and northern Argentina, these lizards can tip the scales at well over ten pounds and stretch nearly five feet from nose to tail tip. Their popularity as pets has created a tangled web of ecological concern, as San Jose’s park rangers made clear in statements to Hoodline.

Their appearance in California is, regrettably, not entirely without precedent. The same Hoodline piece references the 2022 tale of Sully, another wayward tegu, who roamed Folsom’s streets before being returned to its owner—proving once again that “lost pet” bulletins now cover a much broader spectrum than one might expect.

The bigger worry—one underscored by both Hoodline and KRON4—is the tegu’s invasive reputation. In Florida, the species has prompted aggressive removal programs, with state regulations now allowing residents to hunt them without a permit. Georgia and South Carolina have also imposed restrictions and registration requirements on tegu ownership due to the threat they pose to native species. Hoodline further cites U.S. Geological Survey research warning that suitable tegu habitat stretches across much of the American South and parts of northern Mexico, raising questions about the long-term ecological risks of even sporadic escapees.

What Happens When Pets Go Exploring

The pet trade connection is hard to miss: Hoodline draws on research estimating that as many as 79,000 live tegus entered the U.S. between 2000 and 2015, mostly destined for the exotic pet market. Problems tend to arise when large, intelligent lizards either outgrow their welcome or display an unerring talent for escape. As the outlet notes, Sully’s adventure is just one case among many where the boundaries between “backyard companion” and “local wildlife” blur in strange ways.

Park officials, quoted in both KRON4 and Hoodline, have emphasized that tegus typically avoid confrontation with people. It’s their culinary curiosity—especially for eggs of ground-nesting birds and other vulnerable species, as spotlighted in Hoodline—that sets off alarm bells for ecologists. And Joseph D. Grant County Park, as detailed by Hoodline, is no casual greenspace: its expansive habitats support rare and threatened species like the California Tiger Salamander and Tricolored blackbird, for whom an egg-hunting lizard represents a very real problem.

Ecology Meets Absurdity: What Next?

With the current Californian climate generally too cool for tropical lizards to establish permanent populations—a fact clarified by California Department of Fish and Wildlife officials and noted by Hoodline—this latest tegu’s cameo is more a curiosity than a crisis. Still, the pattern is hard to ignore. Are we, with our appetite for the unusual and our often leaky enclosures, quietly assembling the world’s most eclectic open-air menageries? Should “escaped tegu” be a default part of the ranger training manual?

For now, as UPI documents, the recently captured tegu is awaiting either a claim by its owner or (should none materialize) a new, presumably more secure home courtesy of Santa Clara County Animal Services. Park staff are equal parts relieved and bemused.

It’s tempting to see this as a modern fable—reminding us that “just another day at the park” sometimes involves creatures more at home in a David Attenborough special than a Sunday picnic. In an era where lost pets can upend ecosystems and a casual stroll can become an episode of “Planet Earth: Suburbia”, you have to wonder: what unexpected arrivals are still waiting just off the trail?