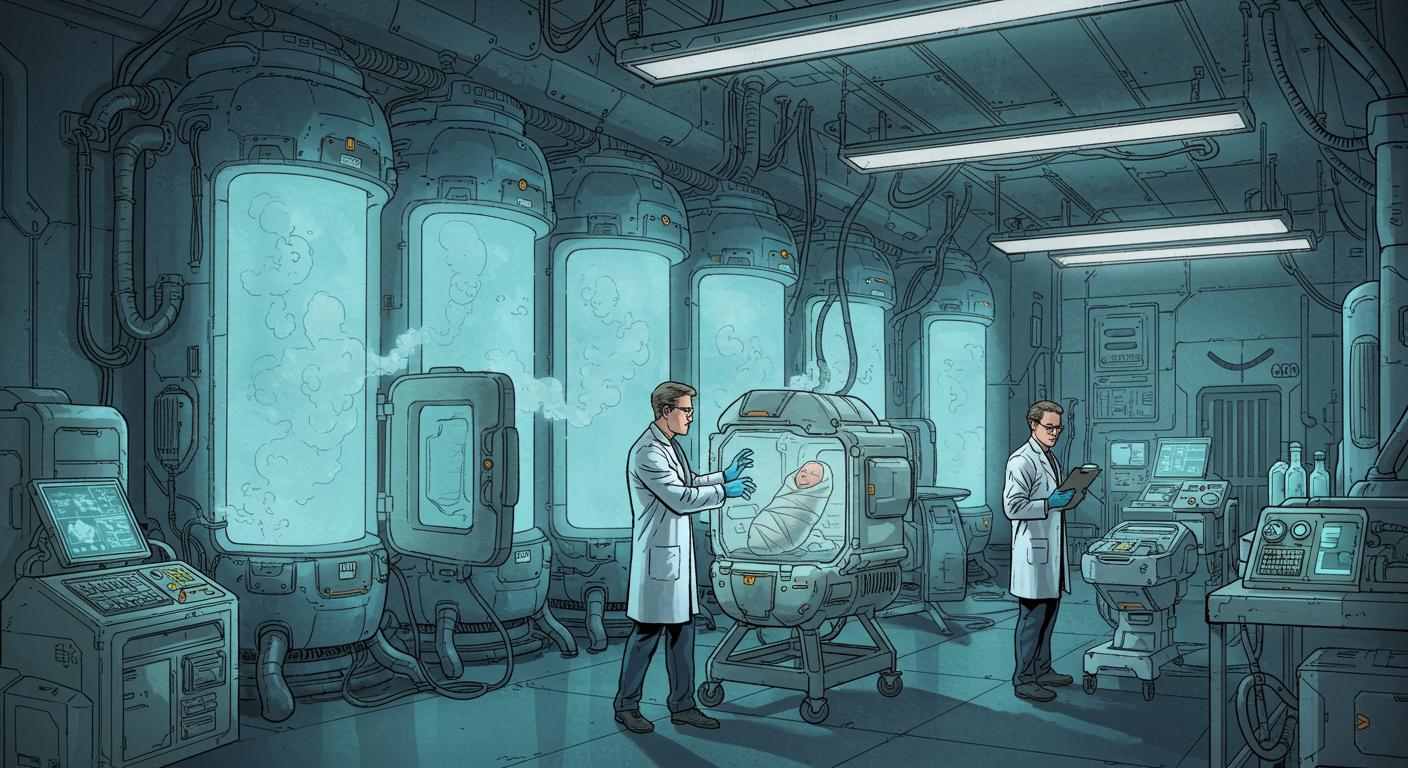

It’s not news that the world, at times, can feel like a David Lynch screenplay—or perhaps something more subtle, a Coen brothers scene played with a straight face. And yet, just when you think time has exhausted its supply of improbable plot twists, along comes Thaddeus Daniel Pierce: a baby born in Ohio from an embryo frozen back in 1994, when Pulp Fiction was still mugging for Oscar voters and dial-up internet was more common than cell phones.

In a detail highlighted by the Guardian, Thaddeus recently arrived on the scene via an adopted embryo—a phrase that, for all its clinical strangeness, maps neatly onto a classic human desire: “We just wanted to have a baby,” his mother Lindsey told the MIT Technology Review, as cited by both main sources. That’s the understated motive beneath a headline that almost sounds like a challenge to every film archivist and medical ethicist alive. Is it odd that the “generation gap” here could include a literal shelf life?

Sibling Rivalry, Brought to You by Cryopreservation

As described in reports from both the Guardian and a more detailed account in the Catholic Herald, the story starts in the early ’90s, when Linda Archerd and her then-husband embarked on IVF, resulting in four embryos. Archerd reflected on her longing for more children, telling the Herald she “always wanted another baby desperately,” and referred to the frozen embryos as her “three little hopes.” Only one embryo was originally implanted, becoming a daughter who is now 30 years old and a mother herself.

The remaining three embryos were consigned to long-term storage—a status often labeled “hard to place” by clinics, as noted by The Times and cited in the Catholic Herald, a term describing embryos considered less likely to result in a healthy birth after many years on ice. While the phrase conjures Dickensian undertones, it’s primarily a technical challenge: After decades in deep freeze, would anyone want them—and what does it take to bring them to the present?

Custody details for the embryos are an unexpected subplot, with the Guardian noting Archerd was awarded custody following her divorce. The process of embryo adoption, she learned, is frequently handled by Christian agencies in the US, and involves preferences from both donors and recipients. Archerd specified a wish for her embryos to be adopted by a white, Christian married couple, a condition that the Pierces—Lindsey and Tim, aged 35 and 34—met after years of trying for a baby themselves. The Catholic Herald specifies the Pierces signed up for the program after seven years of attempting to conceive.

The broader context, as noted in the Guardian, includes the previous record for the “oldest baby” being held by twins born in Oregon from embryos frozen for 30 years. These record-breaking thawings seem more like acts of archival research than medicine—how many possible siblings are quietly waiting in liquid nitrogen for their turn?

Technological Deep Freeze: For Better, Worse, and Altogether Surreal

Stories like this tend to stand as milestones for both the wonders and oddities of modern medicine. IVF, as outlined by the Guardian, now accounts for approximately 2% of all US births and over 3% in the UK. For women aged 40 to 44 in the UK, 11% of births are the result of IVF, reflecting a societal shift described by the Human Fertilisation and Embryo Authority. Statistics on the scale of this technology’s reach make the oddity of Thaddeus’s birth feel almost inevitable. The Catholic Herald references estimates, based on The Times, that millions—possibly tens of millions—of surplus embryos are currently stored in freezers worldwide, with the gap between “can be implanted” and “actually implanted” growing ever wider.

As documented by the Guardian, John Gordon, the reproductive endocrinologist who runs the clinic responsible for Thaddeus’s transfer, is actively working to reduce the number of embryos in storage. Gordon, a Reformed Presbyterian quoted by both outlets, explained, “We have certain guiding principles, and they’re coming from our faith. Every embryo deserves a chance at life and the only embryo that cannot result in a healthy baby is the embryo not given the opportunity to be transferred into a patient.” There’s an almost archival parallel here too—if the record isn’t preserved, no one can access it; if the embryo isn’t thawed and tried, its potential remains forever unresolved. You have to wonder: how many possible futures are out there, stacked quietly in the temperature-controlled recesses of fertility clinics?

“We Didn’t Go into It Thinking We Would Break Any Records…”

For the Pierces, it seems breaking records was the last thing on their minds. In comments shared with the MIT Technology Review and echoed across the coverage, Lindsey said, “We just wanted to have a baby.” The Guardian quotes her describing the ordeal: “We had a rough birth, but we’re both doing well now. He is so chill. We are in awe that we have this precious baby.” It’s a sentiment nearly every new parent could echo, yet here it comes with an extra layer of time-travel magic.

Archerd, meanwhile, remarked on the uncanny resemblance between her new baby son (genetically, at least) and her daughter as an infant, telling the Guardian she compared old photos and “there is no doubt that they are siblings.” The logistics of modern genealogy might be catching up to the emotional complexity: a newborn whose “big sister” is 30, and a grandmother at 62 discovering genetic déjà vu through emailed baby pictures.

Bringing the Past Into the Present (and Vice Versa)

This latest addition to the “stranger-than-fiction” category is a knotty web of timelines, legality, and everyday hope. It pulls together medical technology, patient paperwork, religious conviction, and the ever-present human longing for family. Will Thaddeus someday feel an affinity for the pop culture of the mid-1990s? Will future records be set by embryos frozen twice as long, coming of age with even older pop soundtracks? Both outlets document how Thaddeus’s story is just one outlier among millions of “frozen possibles,” so maybe the real marvel is that these headlines still surprise us.

Somewhere, perhaps, another embryo of similar vintage will soon brush off the frost and join the present. If that isn’t cause to revisit our filing systems—both literal and metaphorical—I don’t know what is.