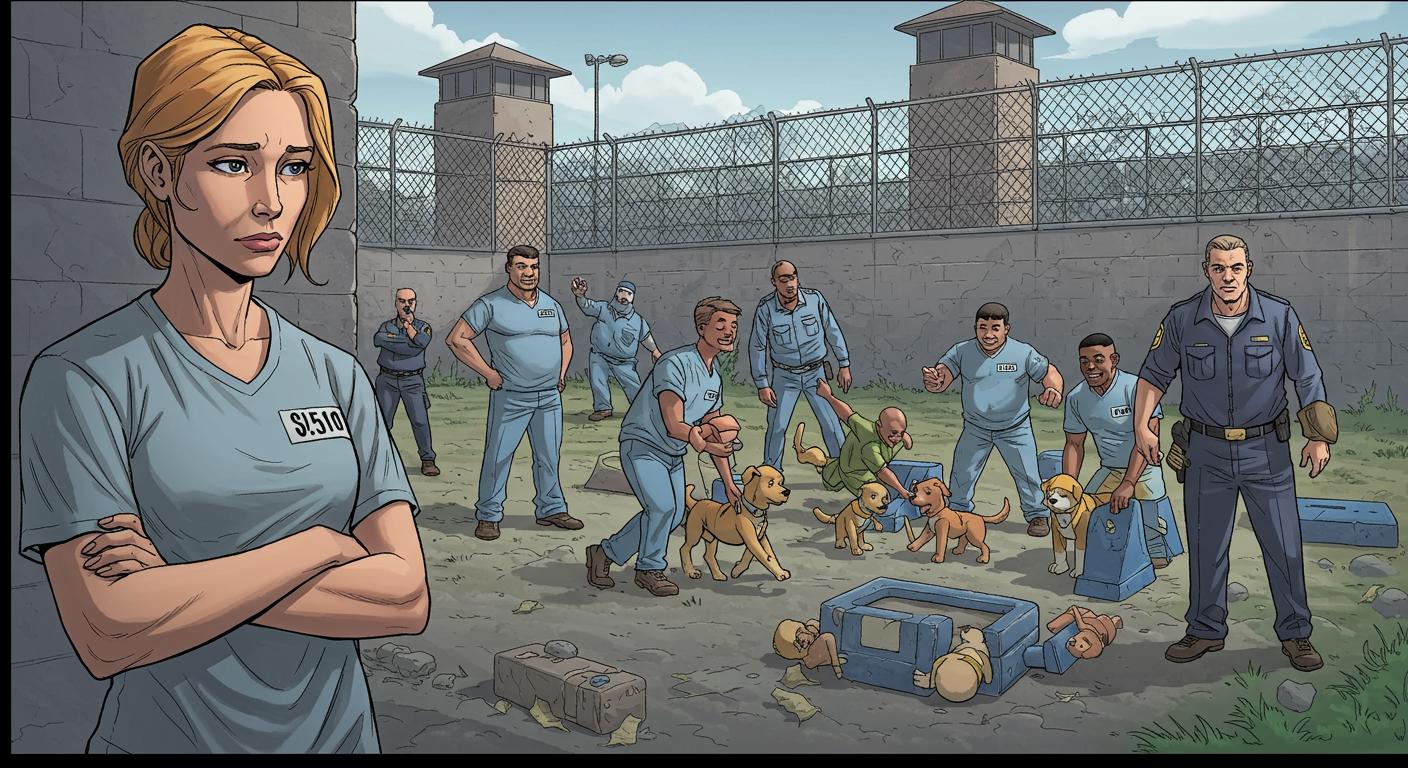

It turns out, even in the famously permissive world of minimum-security federal prisons—a realm sometimes described, with both envy and incredulity, as “Club Fed”—there are horizons that remain distinctly off-limits. The case in point: Ghislaine Maxwell, whose criminal résumé has already granted her a high-profile place among the “celebrity inmates” of Texas’s Federal Prison Camp Bryan, will not be joining the prison’s service puppy training program. As Irish Star reports, and as documented more granularly in Global News, her exclusion isn’t up for debate.

When Even the Dogs Are Off Limits

Maxwell, recently transferred from a low-security facility in Florida to a minimum-security Texas prison camp described as having few physical barriers and a collection of high-profile inmates, will find some amenities notably inaccessible. The service puppy training program, a much-touted feature at Bryan, stands out as the most pointed omission from her prison privileges. Canine Companions, the nonprofit running the program, has set out policies that remain firm: anyone convicted of crimes involving abuse toward minors, crimes against animals, or “any crime of a sexual nature” is barred from participation.

Paige Mazzoni, CEO of Canine Companions, explained to NBC News (as cited across Irish Star and Global News) that these rules are non-negotiable, noting, “Those are crimes against the vulnerable, and you’re putting them with a puppy who is vulnerable.” In other words, not all programs labeled “rehabilitative” are considered suitable for everyone on paper—especially if your history is the exact reason behind those restrictions.

Program details highlighted in Global News show that this isn’t just about playing with adorable puppies. Selected inmates in the Prison Puppy Raising initiative take on primary responsibility for socializing, feeding, exercising, and training service dogs—all under close supervision. The dogs accompany their handlers throughout daily routines: work assignments, meals, and recreation periods, eventually retiring to sleep in the handler’s cell at night. Volunteers unaffiliated with the prison also periodically remove the puppies to expose them to public settings, rounding out a comprehensive socialization regimen. The same outlet notes that the privileges and trust this program embodies are significant, and so are the limits set in place to protect both animal and human participants.

Selective Perks at a Minimum-Security Summer Camp?

The prison itself operates on a model described by both Irish Star and Global News as something close to “the gentler end of the penal spectrum.” Federal Prison Camp Bryan lacks fences, assigns inmates a variety of self-sustaining maintenance work, and offers a suite of programs aimed at smoothing the realities of incarceration. Unsurprisingly, not all perks are distributed based solely on good behavior. The same reporting clarifies the clear rationale: when an inmate’s crime centers on the exploitation of the vulnerable, those vulnerabilities are off-limits—even if they’re four-legged and fuzzy.

It’s hard not to detect a certain symmetry in the system. Maxwell’s exclusion from rehabilitation programs built on trust, care, and vulnerability feels less punitive than, say, poetic. The very aspect of her crime that warranted lengthy incarceration now quietly resurfaces in the day-to-day rules of prison life—no puppy love for those convicted of abusing trust itself.

Meanwhile, the Parade of Notoriety Marches On

Maxwell’s new neighbors reportedly include Elizabeth Holmes of Theranos infamy and Jen Shah from “The Real Housewives of Salt Lake City.” While no updates yet on who runs the prison book club, the presence of such names does raise an ongoing question about the lines drawn—symbolically or otherwise—in these supposedly reform-minded facilities. Does access to comfort or opportunity, even in small doses, speak to justice or simply to a nuanced kind of institutional triage?

Both sources emphasize that Maxwell’s legal team remains vocal, contesting her conviction and advocating for a Supreme Court review. Meanwhile, Donald Trump, when asked recently about any possibility of clemency, flatly denied that anyone had brought the subject to him—a detail mentioned in coverage from the Irish Star and echoed in Global News.

One might wonder, are these institutional distinctions genuinely rehabilitative, or do they mostly serve as reminders—both to the public and to those incarcerated—that some boundaries simply aren’t meant to be tested? And if so, is there something quietly satisfactory about the arrangement, however surreal it sometimes appears from the outside?

Whatever the answer, for now, the rules are clear: for some prisoners, the small redemptions of prison life—whether in the form of frolicking puppies or trust-based programs—are just out of reach, fenced off not by steel, but by policy. Some lines, apparently, remain inviolable, no matter how low the walls.