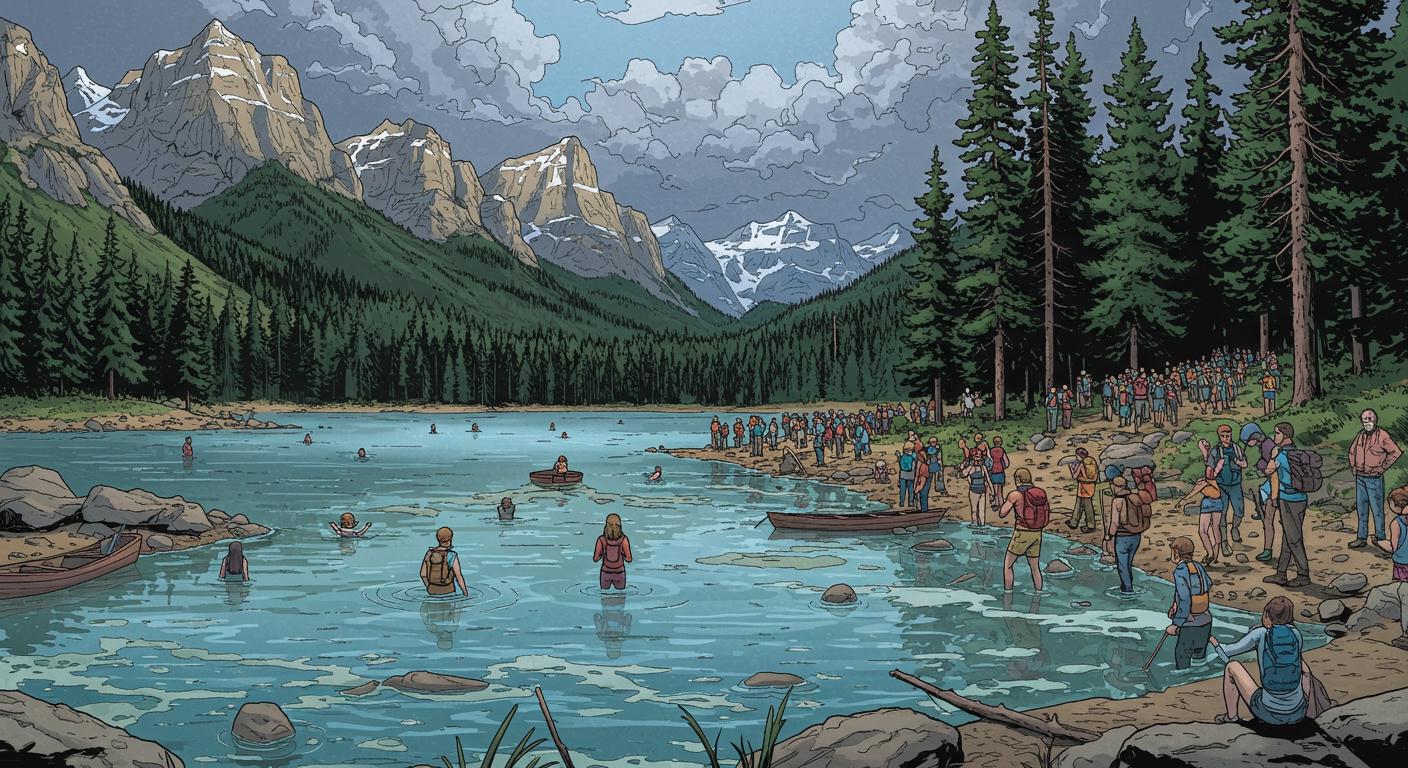

A recent WyoFile investigation has confirmed what seasoned backpackers and local outdoor shop guides have been muttering about for years: Wyoming’s Lonesome Lake is, paradoxically, not very lonely these days—and is now the most fecally contaminated lake surveyed in the entire country by the EPA. Forget secret swims; the real badge of courage might be simply wading in without knowing what’s really floating below the surface.

Lonesome, but Not Alone: Breaking the Wrong Records

Nestled in the Cirque of the Towers—a granite cathedral ringed by glaciers—the setting couldn’t be more spectacular. It’s remote, snowmelt-fed, and sits a stone’s throw from the Continental Divide. But according to data gathered by the Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) in August 2022, the waters here are now home to levels of Enterococci bacteria that are, for lack of a better phrase, hard to picture in real-world terms. The test result? 490,895 calibrator cell equivalents per 100 milliliters. For context, the EPA sets the safety bar for recreational swimming at 1,280 CCE/100 mL. In a detail highlighted by WyoFile, that means Lonesome Lake clocked in at roughly 384 times what’s considered safe for a dip.

And it wasn’t just tops in Wyoming. The EPA’s National Lakes Assessment covered 981 lakes across the country, including the sort usually blamed for such findings: ones ringed by highways, cows, or suburban backyards. Yet the data, the outlet reports, reveal that this tucked-away “gem” now out-pollutes them all—by a landslide, or perhaps more appropriately, a landslide of something else.

The findings, perhaps inevitably, were not made public immediately. As described in the same report, the EPA waited two years to release the sampling results, so summer visitors in 2023 and 2024 were likely to emerge from their refreshing swim blissfully ignorant of any hidden biotic drama.

The Alpine Toilet: How Did We Get Here?

It turns out you can have too much of a good thing—particularly when that thing is popularity. Trail-counter data cited by WyoFile suggests Lonesome Lake draws 250 to 400 wilderness travelers per week at the height of August. Combine that with advice often handed down by word-of-mouth—don’t drink, don’t swim, watch for shallow graves—and you almost have to admire the efficiency of nature’s own “pack-it-in, pack-it-out” joke.

Guides like Brian Cromack from Pinedale’s Great Outdoor Shop, as quoted in the report, describe the situation with a certain grim resignation. Cromack relays, “It’s been heavily contaminated for a long time, just via the negligence of outdoor recreation enthusiasts over the years.” Cromack also contends that climbers make up a particularly dense slice of the visiting crowd, and while he loves climbing himself, he points out their cultural norms aren’t always the cleanest.

And while dogs are present—dogs are permitted and often accompany hikers—some commenters note that horses may play a role, as documented in WyoFile’s review of visitor testimony. It’s a backcountry potluck, but not one anyone would RSVP for.

When WyoFile’s reporter visited in July, he found seven makeshift latrines within minutes—not deep wilderness, just off the main trails. Some were lightly buried; some not at all. Toilet paper and waste routinely surfaces as snow melts and soil shifts. The cumulative effect? According to the outlet, a few quick calculations suggest upwards of 100 pounds of human waste may be left behind weekly during peak usage.

Management Quandaries: Solutions From Helicopters to Groovers

With the issue reaching new heights (or depths), regulators are ramping up their investigation. Details in WyoFile’s summary of the DEQ’s current sampling plan show that both Lonesome and nearby Big Sandy Lake are undergoing five rounds of water testing this summer, specifically tracking contamination during the highest-use weeks. Earlier samples taken well outside the hiking rush yielded no detectable E. coli, underscoring just how much the problem is tied to backpacker influx.

Jeremy ZumBerge, supervisor for DEQ’s Surface Water Monitoring Program, acknowledges in his remarks to WyoFile that the precise transport mechanism for fecal contamination isn’t fully nailed down—though various factors, from shallow burial to snowmelt migration, are all in play.

When it comes to possible fixes, precedent exists nearby. The article describes how Grand Teton National Park requires portable toilet systems for backcountry campers, while some sites rely on helicopter or mule teams to empty outhouses. Special rules are already in place at Lonesome Lake, but whether that’s enough—or even enforceable given the setting—remains unsettled. Ron Steg, DEQ’s Lander Office manager, tells the outlet it’s “a very unique situation to have a water quality issue this many miles into a wilderness area,” and that “if there is a problem,” it’ll “certainly need to be addressed.”

Online and in comment sections, the usual suspects are rounded up: mandatory permits, more toilets (installed and maintained by air), even carry-out regulations—which, as one passing observer admits, would be “pretty tough here, carrying it out.” But as WyoFile notes, limits on use and education programs have worked elsewhere, from Yosemite’s quotas to Washington’s Enchantments area.

The Irony of Pristine Popularity

Perhaps the real kicker is that Lonesome Lake’s problems are, in a weird way, a testament to its power to draw people in. The tragedy-of-the-commons scenario is familiar; what’s noteworthy is the speed and intensity with which even a remote wilderness basin can become overwhelmed. Lonesome Lake occupies a scant two square miles of watershed, so all that “biomass” from hikers, climbers, and canines ends up funneling into a modest area, with predictable (if unsavory) results.

It’s a strange reality: the more revered a wild place is, the less wild—and more, well, shared—it becomes. As WyoFile outlines, the tools for reversing the trend exist, but the appetite or consensus for restricting access to such a quintessential Wyoming experience remains uncertain. Is this just the inevitable byproduct of outdoor enthusiasm and social media-fueled bucket lists, or might the lake’s new title actually shock people into new habits?

Final Reflection

There’s something dryly fitting about Lonesome Lake’s fate—a stunning landscape, loved so hard it’s now home to EPA-defying levels of contamination. Whether this ends with wag bag mandates, airlifted toilets, or simply a generation of people with stronger stomachs, remains to be seen. But one thing’s clear: in the contest between “pristine” and “popular,” nobody expected the most remote site in the survey to win the crown for contamination.

So next time someone tells you to go jump in a lake, you might want to check the lab results first. Or, at the very least, ask yourself how many others—human and otherwise—have been there before you.