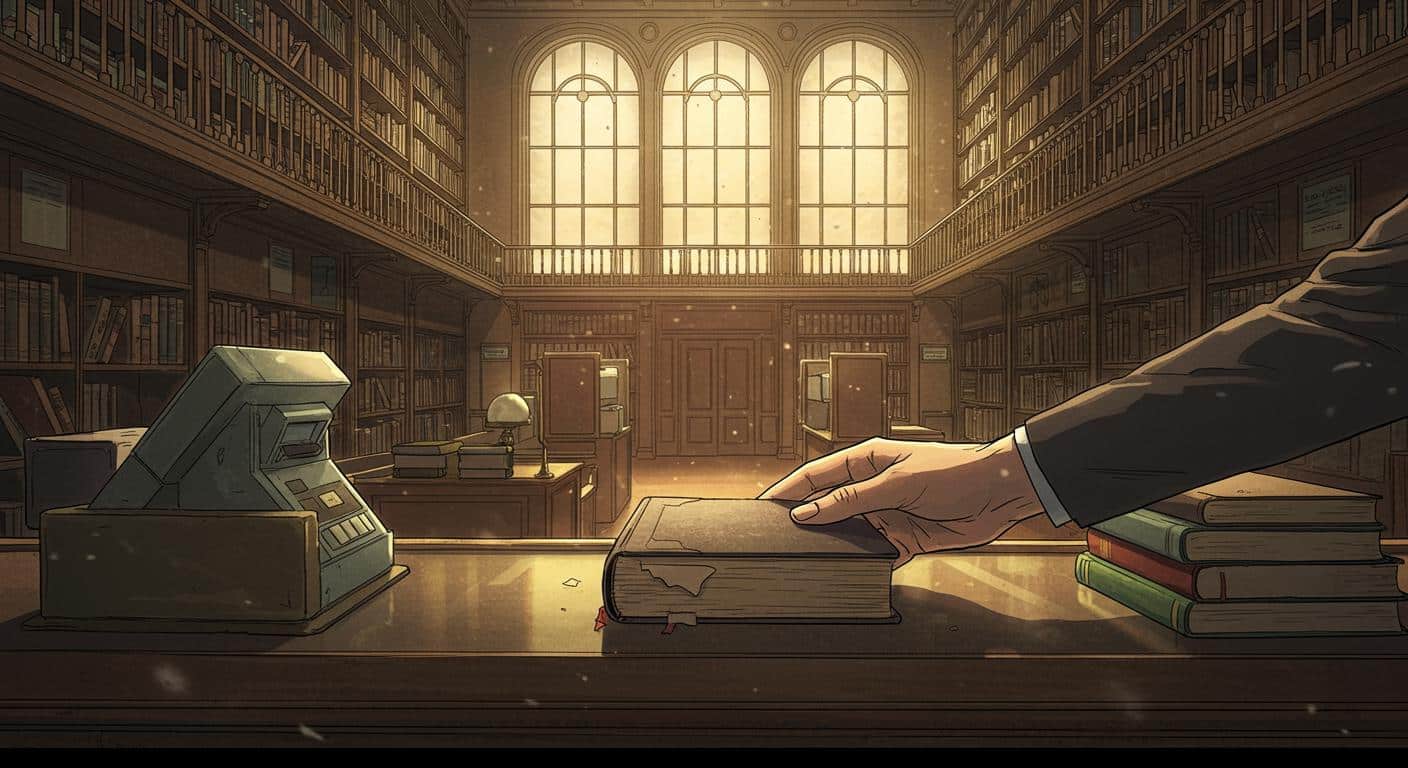

Every so often, a story surfaces from the quiet stacks of daily life that’s just odd enough to make you stop and squint. Take, for instance, the recent return of Your Child, His Family, and Friends—a book checked out from the San Antonio Public Library in July 1943 and mailed home from Oregon, only 82 years behind schedule. It’s the literary equivalent of a Rip Van Winkle nap.

A Journey Through Attics and Decades

By way of background detailed in the San Antonio Express-News, the history here doesn’t disappoint. The book—a self-help parenting guide by Frances Bruce Strain—was borrowed during World War II, presumably with the best of intentions. According to a letter that accompanied the book, cited by Express-News and KSAT, the original borrower was the grandmother of the returning party and checked it out for her 11-year-old son, just before the family’s abrupt relocation to Mexico City for her job at the U.S. Embassy.

Instead of a hasty drop-off at the return desk, the book took the long route through generations, winding up in Oregon after being quietly inherited, boxed, and forgotten somewhere in that nebulous territory known as “family stuff.” The most recent custodian, identified in Express-News reporting only as “P.A.A.G.,” stumbled across the volume while sorting through their late father’s belongings and decided—perhaps out of curiosity, or sheer archival obligation—to mail it back with a note acknowledging the lapse in etiquette.

“When I noticed it was from the San Antonio Public Library, I decided to send it back to you,” the letter explained, as documented by KSAT. There’s a kind of gentleness, and a touch of familial apology, in the additional lines: “She must have taken the book with her, and some 82 years later, it ended up in my possession.” It’s easy to imagine generations of shrugs and good intentions leading up to that moment at the post office.

The Price of Procrastination—Or Lack Thereof

For those counting pennies (and who among library regulars isn’t?), KSAT was told by San Antonio Public Library marketing manager Scott Williams that the fine for overdue books in the 1940s stood at three cents per day. Express-News writers, always ready with a calculator, observe that with nearly 29,891 days of delinquency, an old-school fine would total about $896. Not entirely pocket change, but still less than the cost of a mid-century set of encyclopedias.

All this, of course, if the rules hadn’t changed. Both UPI and KSAT document that the library retired overdue fines in 2021, aiming to “break down financial barriers to accessing library services,” as Williams described. So as for that quip in the letter—“I hope there is no late fee for it because Grandma won’t be able to pay for it anymore”—Grandma and her descendants are officially off the hook.

KSAT also sheds light on the likely outcome if this return had happened decades ago: at a certain threshold, the book would have been marked as “lost,” with the borrower charged only the price of replacement rather than an unconscionable sum. Some might argue that’s a relief for anyone who ever lost a paperback behind the radiator in fifth grade.

Time Capsule on Display

While no one is queuing up for century-old parenting advice, there’s a quiet reverence to be found in the mere survival of this book. Williams described it to KSAT as “a self-help book about parenting from the 1940s,” which he noted was charmingly outdated—a piece of social history more than a guide. The Express-News displays a photo of the battered but intact volume, now sitting in the San Antonio Central Library lobby, a modest attraction until the end of August.

After the brief exhibition, as detailed by both the library’s statements to the media and Express-News, the book’s next stop will be with the Friends of San Antonio Public Library for sale at the Book Cellar, a used bookstore in the basement of Central Library. Which raises the question: what is the going rate for a book with a provenance that’s one part family heirloom, one part bureaucratic comedy of errors?

More Than Just an Oddity

Amid all the calculations and quips, there’s a subtle poignancy to this story. UPI highlights the gentle absurdity of tracking down a decades-old oversight with a note and a smile. The journey of Your Child, His Family, and Friends—across attics, closets, and generations—transforms it from a dusty how-to manual into a well-traveled artifact, a quiet witness to family change and, perhaps, a reminder that even the most minor debts can be paid back in the end.

The letter writer, according to Express-News, even mulled the idea of donating as a token of thanks—a gesture suggesting that gratitude, like overdue books, can endure longer than anyone expects.

And really, who among us hasn’t stumbled across some relic of ancient borrowing and wondered—just for a moment—how many hands it passed through, and what obligations might still linger in the quiet? As Scott Williams put it when speaking to KSAT, outdated books like this can offer “a snapshot of the times.” But maybe they also offer a snapshot of our own flawed, bumbling, and occasionally redemptive relationship with borrowed things.

A Small, Satisfying Circle

At the end of the day, Your Child, His Family, and Friends made it home—more than eight decades late, true, but in decent shape and with a story to tell. The San Antonio library’s decision to embrace forgiveness rather than ledger-book justice feels just right; after all, how many of us want our minor failures to turn, eventually, into amusing exhibits rather than crimes?

Is it merely an oddball news piece, or a tiny, satisfying tale about families, forgetfulness, and libraries adjusting to a world that never quite runs on time? Either way, I can’t help but wonder if there are other silent fugitives still lurking out there—maybe in your attic, maybe in mine—waiting for their own overlong journey to end.