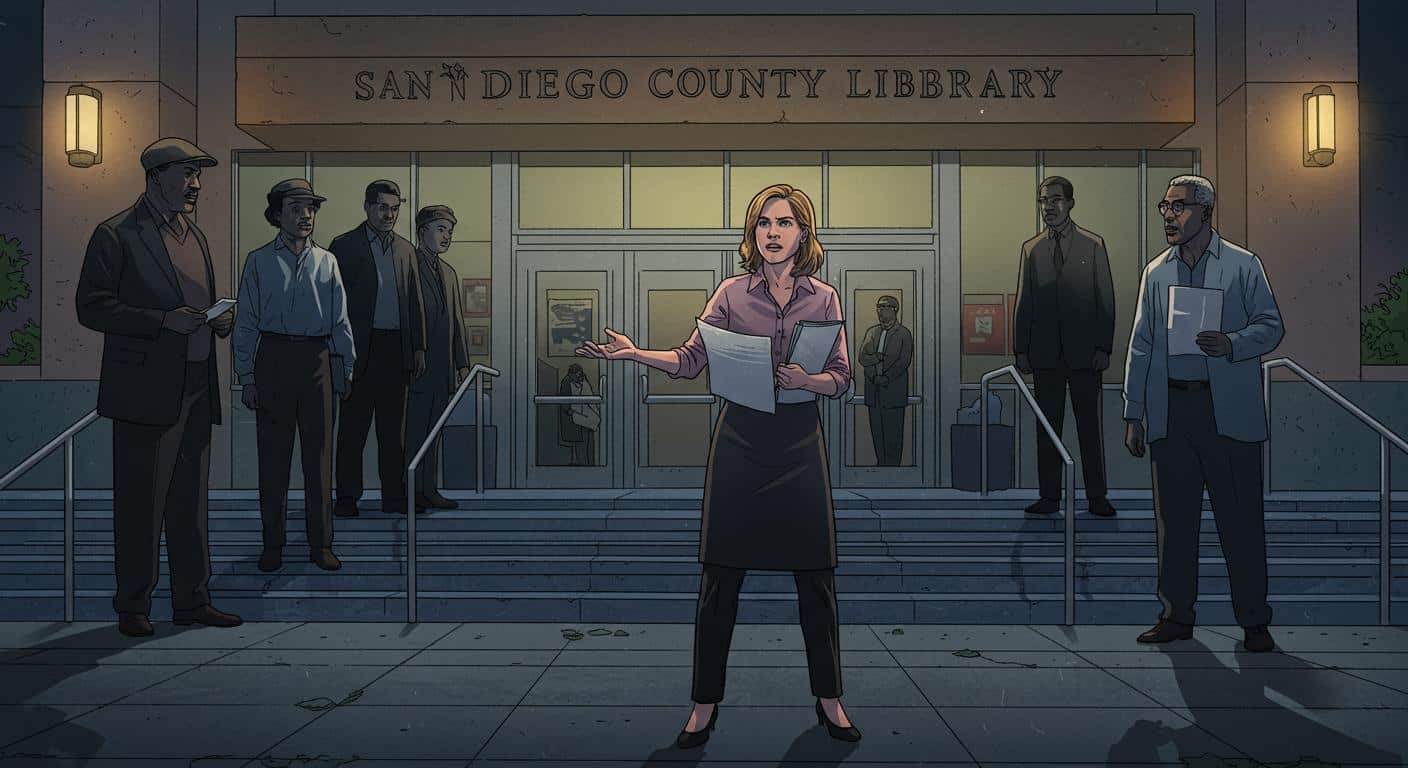

Every so often, an uncommonly strange dispute sneaks out of academia, the theater world, or—unsurprisingly—the public library. The latest case ticks all three boxes. As described in both KPBS and Atlanta Black Star, San Diego County Library is being sued by Annette Hubbell, a white actress, for canceling her Women’s History Month performance because she planned to portray not just white historical figures, but also legendary Black women like Harriet Tubman and Mary McLeod Bethune.

On one side sits a septuagenarian performer who claims she’s honoring heroines she’s meticulously researched; on the other, a government entity—whose fundamental stock-in-trade is stories—deemed her portrayal inappropriate, sparking a legal, social, and philosophical kerfuffle that might make even the most seasoned reference librarian pause over their next program selection.

The Lawsuit, the Library, and the Woman Warriors

The events as chronicled by KPBS and echoed in Atlanta Black Star begin with Annette Hubbell’s “Women Warriors,” a one-woman show where she takes on historical figures from various backgrounds—Harriet Beecher Stowe, Corrie Ten Boom, Harriet Tubman, Mary McLeod Bethune, among others. When Rancho Santa Fe Library engaged her for March 2024, library staff chose a cast list that included both Tubman and Bethune. However, roughly two weeks prior to the scheduled show, administrators requested Hubbell perform only white characters, explaining discomfort with “a white woman” bringing Black icons to life for a library audience.

Hubbell, as detailed in both outlets, was openly perplexed by the request. She saw her performance as a tribute, not an appropriation, and reportedly sought clarification from branch supervisor Rebecca Lynn—eliciting the now-infamous line, “That’s pretty much it,” in response to whether she could “only honor women of courage and integrity if they’re white.” Attempts to compare the library’s request with colorblind casting in “Hamilton” produced more exasperated replies from staff who, in Hubbell’s retelling, acknowledged being unable to fully explain the difference.

Unwilling to alter her program on the basis of race, Hubbell ended up having her show canceled. According to what Atlanta Black Star documents, she brought her objection to the attention of the county Diversity and Inclusion Team, who sided with the branch decision, finding no discrimination in the request. After Hubbell shared her experience on social media, her story attracted legal advocates at the Pacific Legal Foundation—an organization known for challenging government use of race as a deciding factor. The result: a federal lawsuit alleging racial discrimination under civil rights law.

“I think if people thought I was doing blackface or a parody, then that might be cause for objection,” she explained in comments to KPBS and expounded in an opinion piece referenced by Atlanta Black Star. “But all they have to do is read my stories and the testimonies on my website, and they would see how deeply I respect and honor and admire these people.”

Her lawsuit, filed in early May, alleges the library denied her “the opportunity to pay tribute to America’s heroines solely because of her race,” invoking the Fourteenth Amendment as well as federal and state anti-discrimination measures. As Atlanta Black Star further reports, Hubbell also claims reputational harm and lost performance opportunities following the public cancellation.

When Colorblind is More Than an Eye Test

Both publications recount how Hubbell and her attorneys draw parallels to the colorblind casting of “Hamilton”—with Hubbell asking, “How is this any different?” and staff responses ranging from “That was historically different” to an admission that the difference couldn’t be fully articulated. For legal precedent, Atlanta Black Star details how the library’s legal team cites federal decisions supporting a government entity’s right to curate programming as a form of expressive speech.

Yet, as both KPBS and Atlanta Black Star observe, this dispute goes beyond mere policy. For many in the arts and library sectors, colorblind casting—often lauded as progressive—originated as a counterweight to eras when roles for people of color were limited or outrageously stereotyped. Angie Chandler, an arts educator and performer cited in both sources, puts it this way: “It’s not a two-way street because colorblindness is a response. A response to historic exclusion, to the erasure of our stories and our parts of different chapters in history in this country.” According to her, even an earnest, well-researched portrayal by a white actress cannot be separated from a legacy in which Black voices have struggled—and still struggle—for the opportunity to speak for themselves on stage.

Chandler, who has played Harriet Tubman, reflected on the significance of body and history in such roles, telling KPBS about the daily realities faced by Black women like Bethune—realities she says a white performer can reference but not inhabit. She punctuates the core of this dilemma: “The foundation of the American arts movement means that it will never be as simple, innocent and neutral for a white person to attempt to tell or perform the story of a Black person.”

Split Shelves: Law, Libraries, and Artistic Lines

Legal arguments, as described in both reports but particularly expanded upon by Atlanta Black Star, have now entered the First Amendment maze. The library, as expressed in its motion to dismiss, asserts its right to produce programming in line with its expressive goals, warning that forced “colorblind” inclusion could upend its ability to curate content ranging from storytimes to drag performances. The defense draws comparisons to cases like Green v. Miss USA, cited by Atlanta Black Star, indicating that compelled inclusion—no matter how well-intentioned—could violate an institution’s free speech rights.

At the same time, the lawsuit is not strictly hypothetical. According to both KPBS and Atlanta Black Star, Hubbell and her legal team seek not only personal redress, but an injunction preventing all future library programming from considering race in casting or program approval—a request that would apply to actors and, conceivably, other performers as well. The potential influence, as recent reverse-discrimination precedent in California demonstrates, could ripple far beyond this single library contract.

Between Portrayal and Parody: What’s the Real Issue?

Comments from the wider public, and from artists embedded in the field, reveal an unresolved tension. Is a respectful, makeup-free, research-driven portrayal by a white woman of Black iconography inherently wrong—or simply awkward in the current social climate? KPBS notes that Hubbell herself seems bewildered by the pushback after years of what she says were well-received performances at venues of every political stripe.

The dilemma remains: should the freedom to present history be limited by threat of discomfort, or does honoring lived experience require a deference to storytellers who share that experience? Libraries, for their part, are caught in the contradiction—championing open access while also acting as cultural stewards responsible to their communities’ sense of inclusion and equity.

And Atlanta Black Star’s coverage underscores how litigation of this sort places a spotlight not only on theatrical practice but on how public spaces navigate the fraught boundaries of free expression, representation, and public purpose.

Hushed Voices or Open Stages?

It’s hard not to notice a streak of historical irony running through these dusty book stacks and now, apparently, courtrooms. Libraries, built to be homes for many voices on many shelves, become battlegrounds over who may speak—and how. While books quietly keep company regardless of their authors’ backgrounds, the live stage resists that kind of neutrality.

Is a story less valid—less powerful—because of the body through which it’s told? Or is there something essential, perhaps even reparative, in allowing certain voices space to narrate their own histories?

You have to wonder: if this one-woman show played before a house full of librarians, artists, legal scholars, and civil rights veterans, would any two agree on where to draw this particular line? Like the best (and messiest) library disputes, maybe the real answer gets filed under “It’s complicated,” somewhere between biography, drama, and local history.