It’s not every day you see a ballot that reads more like the world’s driest phone book than an election. Yet, in Alberta’s Battle River–Crowfoot riding, voters are being treated to exactly that: a federal byelection with a record-shattering 214 candidates. According to CTV News, this isn’t just the largest candidate lineup in Canadian history—it’s the ballot equivalent of a parking lot filled end to end with campaign posters.

The Protest Ballot: Numbers as Message

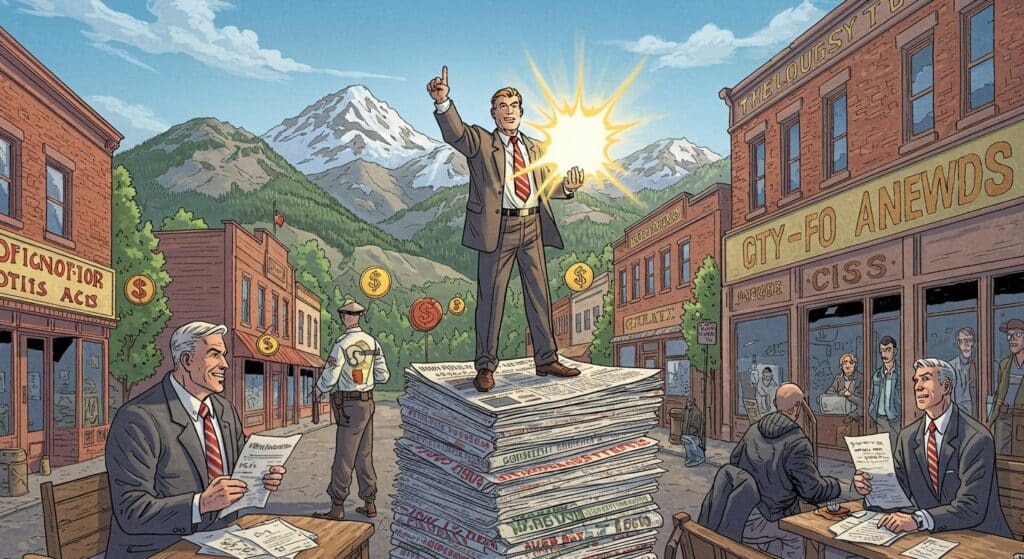

Browsing through the details highlighted by CTV News, it quickly becomes clear this isn’t a case of spontaneous civic enthusiasm. The surge is largely orchestrated by the Longest Ballot Committee, an advocacy group doubling down on its campaign for electoral reform. Most of these candidates aren’t household names; in fact, most aren’t local names either. Their presence is intended as a protest against Canada’s First-past-the-post (FPTP) system—a ballot as demonstration, or perhaps a demonstration as ballot.

For those entering the single advance polling site in Drumheller, the experience is surprisingly undramatic. Voters like Roger Hanm and Brad Luchak described it as “pretty straightforward” and “no problem at all,” even as they faced row after row (after row) of unfamiliar names. Elections Canada, preparing for the logistical mayhem that could arise from such an unprecedented ballot, implemented an adapted write-in system. Instead of ticking a box, voters write their preferred candidate’s name onto the ballot while consulting reference lists stationed like cheat sheets just off to the side.

Thomas Laffin, who cast his vote among the sea of names, found the system manageable—with a “big book” listing every candidate alphabetically, and a smaller party-based guide for those wanting a more familiar approach. So, while the protest may be elaborate, it seems Canadian pragmatism prevails: armed with lists and pencils, most voters take it in stride.

Political Theater or Democratic Headache?

While this election’s bloated ballot is earning side-eyes and sighs, there’s method behind the ballot-box madness. CTV News explains that the Battle River–Crowfoot riding leans deeply Conservative; outgoing MP Damien Kurek previously won with a whopping 83% of the vote. Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre, whose parliamentary comeback hinges on this by-election, is considered almost guaranteed to claim the seat. Political scientist Lori Williams, from Mount Royal University, told the outlet that anything short of another landslide will have poll-watchers asking uncomfortable questions about Poilievre’s standing.

And what does Poilievre himself make of the spectacle? Unsurprisingly, he’s not amused, condemning the Longest Ballot Committee’s approach as a “blatant abuse” of democracy and promising to push for electoral law changes to keep future ballots from resembling small-press anthologies. The outlet notes the Committee pulled a similar move in Poilievre’s former Ottawa-area riding, Carleton, netting an already eye-watering 91 candidates there—well shy of this current record, but still enough to raise eyebrows (and, perhaps, voter blood pressure).

When Choice Becomes a Maze

Is this a grand experiment in democratic abundance, or a cautionary tale in ballot design? For some, the flooded field is more headache than celebration. Adrine Giles, a voter quoted in the CTV report, felt the super-sized menu only made things murkier: “It’s just not really a good idea. You just confuse people.” Giles, who didn’t cast her ballot for Poilievre, also questioned whether leaders not from the area could really represent local interests—an age-old concern, only now echoing down an unusually lengthy candidate list.

Yet, others saw little cause for alarm. Art Bonaguro figured his vote needed to go to the party leader (“I know he doesn’t live in the riding, but the leader of the party really needs a seat in the house to do anything”), a practical stance in a byelection dominated by national strategy as much as local preference.

The Limits of Electoral Abundance

Democracy, in theory, welcomes all comers. But somewhere between “healthy competition” and “214 names to choose from,” the lines blur between empowerment and overload. The mechanics of voting handled the onslaught, with clear instructions and plenty of reference material, but does a ballot at this scale help—or does it simply become its own punchline?

Ballot bloat, especially of the deliberately orchestrated variety, spotlights the quirks (and, in the eyes of reformers, flaws) of the FPTP system. Is this the kind of attention electoral reformers hoped for, or will it just be remembered as the year the ballot looked more daunting than a tax form in April? Democracy often finds itself tangled in numbers and procedures. Here, it’s tangible: a civic experiment, a protest, and perhaps a new high-water mark for political trivia fans.

A democracy where anyone can run certainly delivers surprises—sometimes, whole pages of them. Is this a harbinger of meaningful change, or fodder for stories told at future election night parties? Canadians (and, perhaps, future ballot designers) will be pondering that long after the last write-in vote is counted.