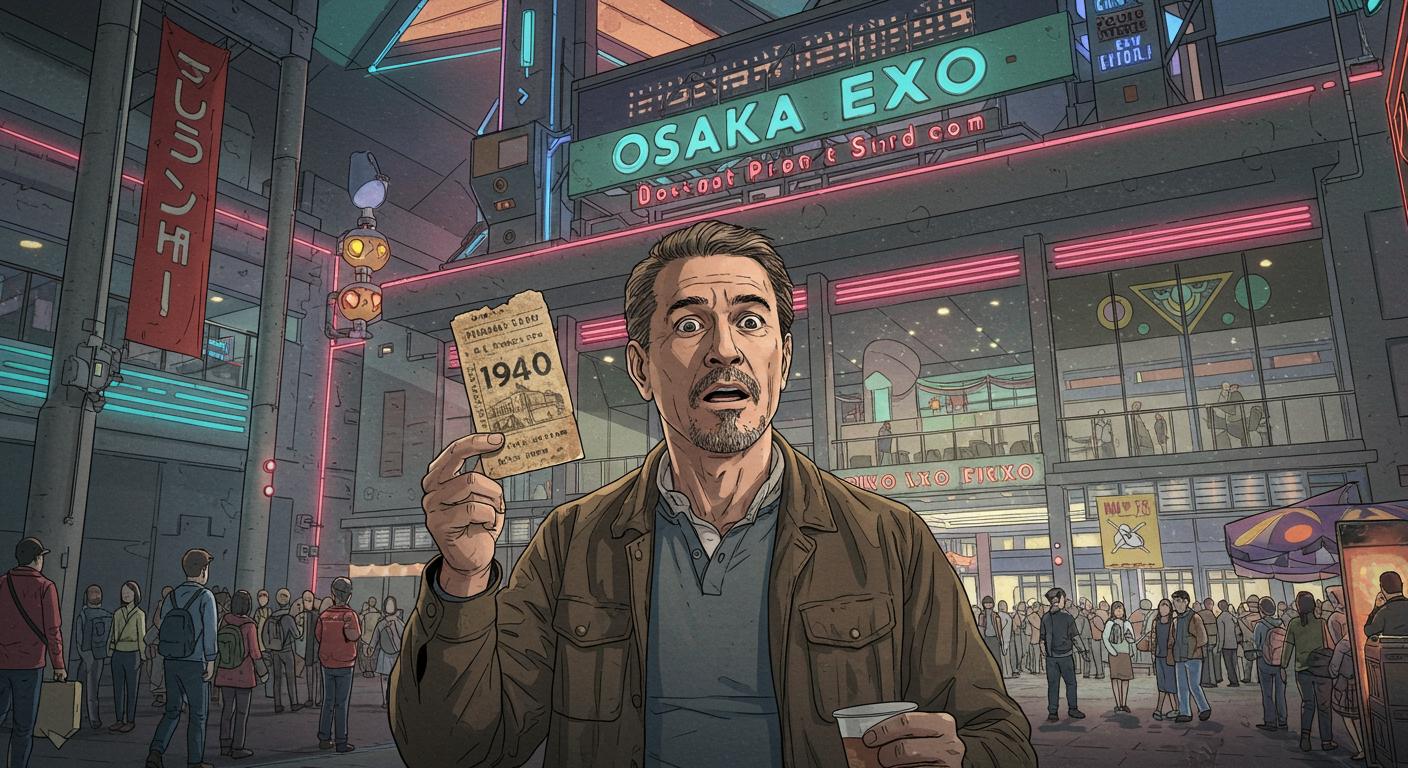

There are stories about lost tickets to events that never happened—sometimes they turn up inside a book or in a grandparent’s attic, typically decades past their sell-by date. But in what feels like an extremely elongated case of “the show must go on,” someone has managed to use their ticket, eighty-five years late, to enter the latest edition of the Osaka Expo. The details, recounted by The Mainichi, are oddly reassuring about the persistence of bureaucratic goodwill—yes, even across generations.

Admission: 1940s Style

According to The Mainichi, Fumiya Takenawa, a 25-year-old company worker and self-admitted expos-enthusiast, showed up at Expo 2025 Osaka, Kansai, wielding an admission ticket for what would have been the 2600 Japan International Exposition in 1940. That original “international exposition” was intended for Tokyo but got quietly scuttled when Japan’s involvement in the Second Sino-Japanese War ramped up. The event faded into history—tickets, not so much.

What’s curious is that this 1940 ticket wasn’t gathering dust in a relative’s photo album or lying forgotten among war-era ephemera; Takenawa found and bought it online this year. (Apparently antique Expo fare is just an auction search away.) As The Mainichi reports, he displayed it at home at first—one imagines a sort of miniature shrine to events that time forgot—before reaching out to the Japan Association for the 2025 World Exposition on a whim. Organizers told The Mainichi they’d honor the admission if the ticket was genuine and met “the requirements,” which is refreshingly lacking in small print or gotcha clauses.

Reuses and Regrets

The Mainichi also notes that the saga of these tickets has some historical precedence. Among World’s Fair collectors and trivia-hunters, the 1940 event is sometimes called the “phantom expo,” both because it never happened and because its tickets have a tendency to make unexpected appearances decades later. Unused tickets were accepted at the 1970 Osaka Expo, with around 3,000 such exchanges that year, and they were exchanged at the 2005 Aichi Expo as well (about a hundred instances then).

For 2025, an association representative cited in The Mainichi explained that expo officials will exchange each unused 1940 ticket booklet for two adult day passes, with the booklet returned to the owner after verification. The booklet’s original price was 10 yen in 1938, which the association estimates as roughly 17,000 yen (about $118) today. Returning each booklet to its owner might offer peace of mind to collectors and archivists—no rescue operations required in convention center bins this year.

A Ticket, a Bridge, a Time Capsule

What stands out, aside from the practical detail that you can apparently redeem pre-WWII event tickets for contemporary perks, is how the story manages to bridge personal and collective memory. Takenawa, who seemed genuinely delighted, told The Mainichi his aim was to “clear the regrets of the person who couldn’t attend the Expo that they must have been looking forward to.” It’s a classic example of an individual turning a collector’s curiosity into a shared, if somewhat symbolic, act of remembrance. He plans on returning to the expo with each family visit, and specifically wanted to see the Czech and Saudi Arabian pavilions—a detail that grounds the whole episode pleasingly in the present.

There’s always a risk, when institutions honor the past, of descending into pure nostalgia or empty pageantry. But reacting to a visitor armed with an eighty-five-year-old “phantom ticket” not with eye-rolling skepticism, but practical accommodation, feels quietly subversive. It’s hard not to wonder which other forgotten relics could still grant us unexpected entry today—what else is grandfathered in, simply because no one ever officially said “the offer expires”?

In any case, it’s more than a quirk of event policy. There’s a lesson here for archivists and collectors alike: sometimes, just sometimes, the past has a way of showing up on your doorstep—completely valid, no expiration required.