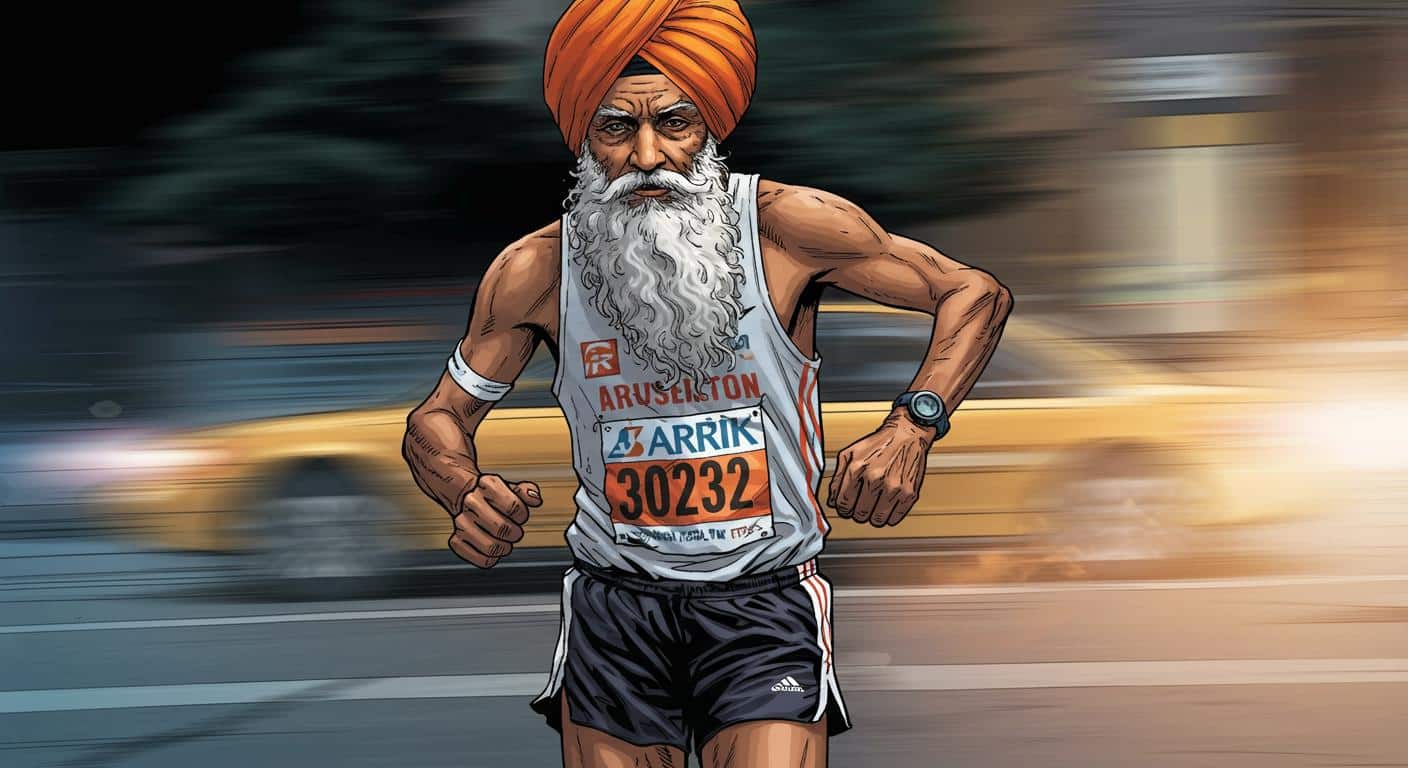

Sometimes fate reveals a wicked sense of irony—none more so, perhaps, than when a centenarian celebrated for outpacing the march of time is suddenly brought to a halt by the most ordinary hazard of pedestrian life. Fauja Singh, inarguably the world’s oldest marathon runner and long dubbed the Turbaned Torpedo, died at the age of 114 after a car struck him while he was crossing a road in Punjab, India. Reports reviewed from AP News, Daily Journal, and MundoAmerica confirm the hit-and-run incident occurred in his birthplace, near Jalandhar, ending a life defined by both improbable endurance and, ultimately, the randomness of daily peril. His London-based running club and charity, Sikhs In The City, confirmed his death, and coverage from both AP News and Daily Journal notes local media reported he sustained severe head injuries in the accident before being taken to the hospital, where he later died.

A Legacy Both Documented and Disputed

By now, Fauja Singh’s feats have become the stuff of Guinness-level legend, albeit not always Guinness record-books themselves. He set out, at age 100, to become the oldest person to complete a marathon—the 2011 Toronto race saw him cross the finish line with the kind of unhurried defiance familiar to anyone who’s ever outlasted expectations. According to AP News and the Daily Journal, the lack of an official birth certificate kept Guinness World Records from inscribing his time into their canon; Singh carried a British passport listing his birth as April 1, 1911, but as Indian officials explained, records simply didn’t exist in his rural Punjab village back then.

Described in MundoAmerica, it’s a punchline fit for bureaucratic comedy: a man who lapped us all in life, yet couldn’t satisfy the paperwork requirements. How often do people who literally outlive the system still fail to meet its technicalities?

Triumph Born of Tragedy

Many who only saw Singh at marathon podiums or as an Olympic torchbearer might assume a lifelong passion for sport. In truth, as illuminated in both AP coverage and further details cited in MundoAmerica, Singh laced up his running shoes for the first time at 89. It wasn’t the thrill of competition but profound grief that drove him forward. The story, almost Shakespearean in its depths, has Singh losing his wife and his son in quick succession; his son’s death—caused in a violent farming accident—is described by both AP News and the Daily Journal as a pivotal, life-shattering moment. Both recount that Singh and his son Kuldip, farmers together, were out in the fields during a storm when Kuldip was killed by a piece of corrugated metal carried by the wind.

Singh, left alone as his five other children had emigrated, moved to London to live with his youngest son. There, as noted in the Daily Journal, Singh attended Sikh community sports tournaments and took up sprinting before meeting marathon runners who encouraged him to try distance running. The rest, of course, became a saga: at 89, in 2000, Singh ran his first London Marathon and went on to complete eight more. His best time came at age 92 during the 2003 Toronto Marathon, clocking in at 5 hours and 40 minutes.

As Singh himself told AP News, “From a tragedy has come a lot of success and happiness.” It’s a sentiment that, while tidy for headline writers, reflects a rare capacity for transmuting sorrow into momentum—literally.

Not Just a Runner, But an Inspiration

Singh’s achievements reached beyond finish lines. As AP News recounts, he was a torchbearer for the 2012 London Olympics—a real-world Forrest Gump moment—and captivated audiences worldwide. MundoAmerica notes his story was captured in the biography The Turbaned Tornado by Khushwant Singh, and he received the Order of the British Empire in 2015, accolades that recognized more than just the miles.

The Governor of Punjab, Gulab Chand Kataria, took to social media to express that Singh joined a march “with an uncrushed spirit” and predicted his legacy would “continue to inspire.” Meanwhile, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi remarked, as cited in the Daily Journal, that Singh was “extraordinary because of his unique persona and the manner in which he inspired the youth of India on a very important topic of fitness.”

After retiring from competitive running at age 101, Singh expressed a simple hope: “people will remember me and not forget me,” wishing to be included and “not forgotten altogether just because I don’t run anymore.” Judging by the global outpouring marked by tributes from his biographer Khushwant Singh and heartfelt send-offs from public officials, it’s safe to say that’s one wish assuredly fulfilled.

Death, Absurdly Ordinary

All this leaves us with the most jarring detail: a marathoner whose very life was a sustained argument against the ordinary limitations of the body, brought down not by age or illness, but a passing car. Authorities, both AP News and Daily Journal note, are still searching for the hit-and-run driver, a faint note of unfinished business.

Perhaps the most peculiar aspect of Singh’s passing is its normality. We expect icons to depart in dramatic, befitting fashion—a poet might hope for thunderbolts; an athlete, perhaps, for the finish line. Instead, as is so often the case, life simply switched tracks on him midsentence. Is there any better indicator of just how random and absurd our endings can be than this?

The Long Road Remembered

In reflecting on all this, I can’t help but marvel at the strange confluence of endurance, tragedy, bureaucracy, and, finally, banality that defined Fauja Singh’s journey. He ran to escape heartbreak. He ran to find something worth waking up for. He set records no one could quite verify, and accepted honors that everyone seemed to agree had been earned. In the end—after 114 years—he was felled by the very real, almost comedically mundane danger that doesn’t discriminate by age or achievement.

So, does it take away from the legend? Or does it weirdly cement it? Perhaps there’s something fitting in the reminder that, however extraordinary the life story, we all eventually have to cross the street. And for a man who spent decades proving the world wrong about its limits, maybe the most lasting message is that the run itself, not the ending, is what people will remember.