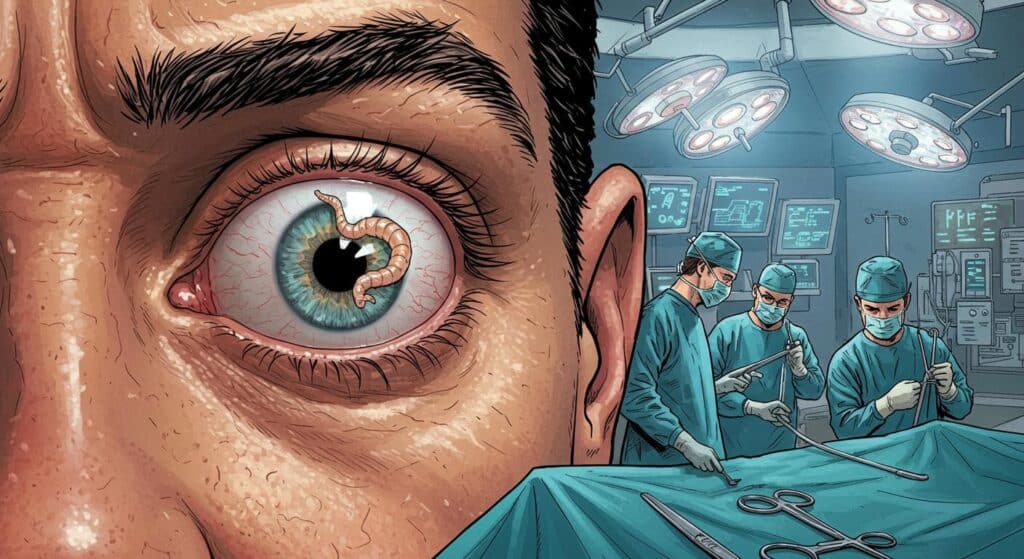

Sometimes, innovation arrives in the oddest of packages—or, as it happens, cavities. If someone told you future eye surgery would call on a molar for backup, you’d be forgiven for assuming they’d mixed up their medical journals with tales from Ripley’s. Yet as CBC News recounts, that precise blend of dental and ocular ingenuity has restored sight to Gail Lane, a 75-year-old resident of Victoria, British Columbia, who spent a decade unable to see her own reflection or even the wagging tail of her service dog.

A Decade Without Sight: The Unusual Road to Recovery

Lane’s story, as CBC details, began with an autoimmune disorder that irreparably scarred her corneas about ten years ago, robbing her of her vision and much of her independence. Navigating daily life became a team effort—with Lane relying on both technology and her partner’s service dog, Piper, to make color-coordinated clothing decisions or simply get around safely.

Eyebrow-raising as it may sound, her pathway back to sight hinged on an operation that required a bit of oral archaeology first. CBC explains that Lane was one of just three Canadians at the time to undergo the rare osteo-odonto keratoprosthesis, or “tooth-in-eye” surgery. The basics? The patient’s own tooth is harvested, then waits out a stint nestled in their cheek for months while connective tissue takes hold. Only after this period is the dental segment—with connective tissue in tow—used as a base in the eye socket, acting as a host for a plastic focusing lens.

Dr. Greg Moloney, the ophthalmologist at Vancouver’s Mount Saint Joseph Hospital who led the groundbreaking procedure, described the logic to CBC; the tooth offers a natural and resilient anchor for the lens, greatly reducing the risk of the body rejecting the implant. According to Moloney, the operation essentially “replaces the cornea”—although swapping enamel for transparency makes for quite the medical leap of faith.

Regaining Sight, Piece by Piece

Lane recalled to CBC that the recovery, while lengthy and at times uncomfortable, produced moments she describes as “well, well worth it.” There’s something quietly spectacular in the sequence she described: the earliest glimmer of light, the first discernible movement, then the familiar shape of Piper’s black Labrador tail finally coming into focus after so many years of darkness.

Six months after her surgery, Lane saw her partner Phil’s face for the first time, having met him after her loss of sight. CBC passes along her understated amazement as she reports recognizing facial features on others, still waiting for the moment when she’ll be able to fully see her own face—perhaps with the help of new glasses on the horizon.

Another shift, perhaps less glamorous but no less meaningful, came when Lane could independently assemble her wardrobe, foregoing the volunteer-driven Be My Eyes app that once told her which colors wouldn’t clash. The sense of autonomy—of picking out her own clothes and taking walks unaccompanied—is what excites her most. “I’m hoping to have more mobility and independence in terms of short trips and walks here and there where I don’t always have to have someone’s arm,” Lane told CBC, emphasizing how even small slices of independence can add up to a big difference.

Inventiveness at the Margins of Medicine

The sheer inventiveness at play begs the question: why a tooth? Moloney explained to CBC that the tooth, with its sturdy makeup, is ideally suited to host the lens without being rejected or degrading over time—a quality soft tissue alone can’t match. It’s an elegant collision of necessity and anatomy: using one of the body’s most enduring materials to restore one of its most delicate senses.

After being asked, Lane told CBC that the difficult logistics and discomfort didn’t deter her, and that patience—waiting for her brain and eyes to work in tandem again—remains part of her journey. The outlet also notes that while globally this procedure isn’t new, Lane stands out as one of the first to benefit from its arrival in Canada thanks to Dr. Moloney and his team.

Are we at the start of a period where rediscovered body parts might help us out in unexpected ways? Or does this remain a tale for the edge cases—a test of human ingenuity when standard options run out?

Either way, Lane’s story is a reminder that sometimes the answer to a seemingly impossible problem is already somewhere on hand—nestled, perhaps, right in your own grin. Science can be strange, but, as ever, reality manages to outdo fiction with a certain gleaming confidence.