Those with a penchant for historical oddities or a suspiciously large cache of pandemic-era trivia cards might want to brace themselves. Reports from Straight Arrow News confirm that a patient in northern Arizona has died of bubonic plague, the same disease responsible for decimating medieval Europe. Yes, that plague—the one with the “bring out your dead” vibes. Despite modern medicine and the reassuring glow of LED triage signs, the world’s oldest nightmares sometimes refuse to stay politely in the past.

Prairie Dogs: The Unwitting Harbinger

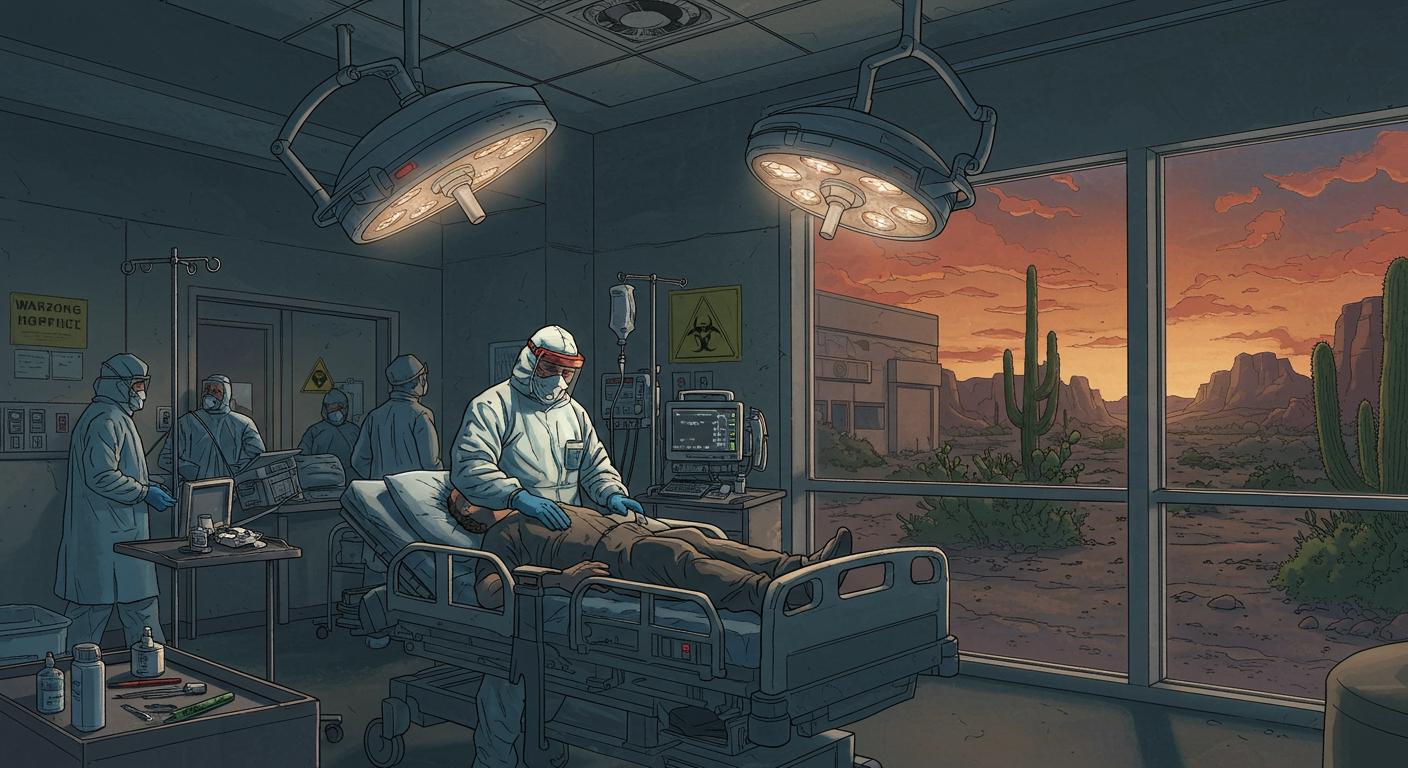

The unidentified patient reportedly arrived at Flagstaff Medical Center’s emergency department and died the same day, according to statements relayed by Northern Arizona Healthcare officials and obtained by NBC News. Health workers determined the cause was Yersinia pestis, a name most people recognize from dusty world history textbooks or, perhaps, casual jousting with Wikipedia’s “List of Unpleasant Ways To Go.”

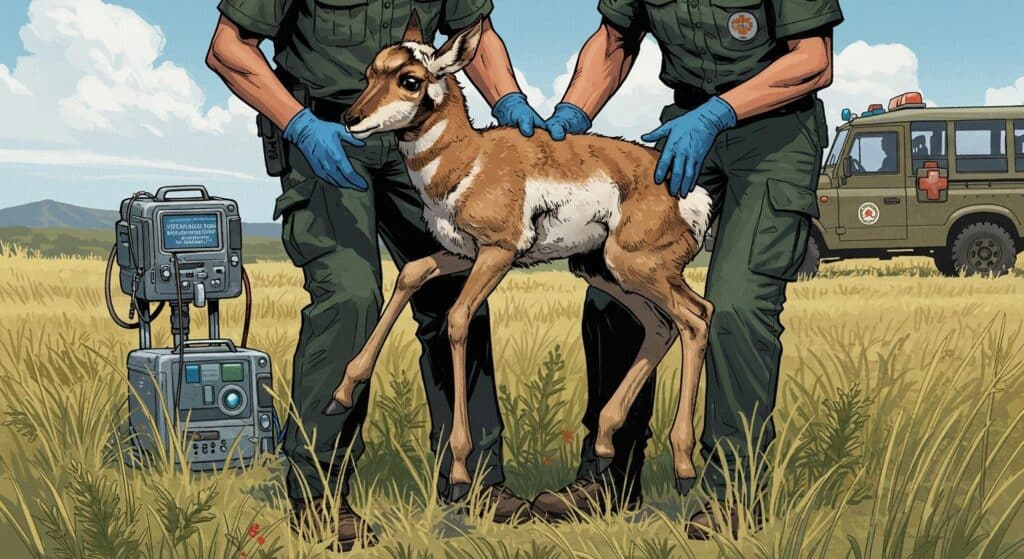

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, whose archives contain more references to disease vectors than most libraries’ fiction sections, attributes most modern infections to flea bites from rodents or direct contact with animals carrying plague. Not exactly a glamorous legacy for prairie dogs, whose recent mass die-off on private land northeast of Flagstaff has caught the attention of Coconino County Health and Human Services. As the outlet documents, this sort of wildlife event is considered a classic indicator of plague activity in the region.

County officials, working alongside state agencies and the property owner, are now collecting flea samples from those burrows for testing—a process likely less thrilling than it sounds. Similar efforts occurred in 2017 after another local outbreak, when county investigators discovered plague-carrying fleas in area rodents, a detail emphasized by Coconino County records cited in the report. Steps being taken now include treating the prairie dog burrows to control the flea population and increasing surveillance in the area.

Plague, Unpacked: The Numbers and the Nuance

It’s easy to conjure images of spectral doctors in beaked masks, but the actual risk today is low. The CDC reports an average of seven plague cases in humans annually in the United States—a handful, but enough to keep infectious disease experts on their toes. Not all of these cases are fatal. As described by the Cleveland Clinic and echoed by public health statements, prompt antibiotic treatment typically cures bubonic plague, provided it’s caught in time. The Arizona patient’s rapid decline is an unfortunate outlier, a reminder that while rare, the disease isn’t relegated to history just yet.

For anyone who’s ever cataloged mysterious aches after hiking, the symptoms can sound distressingly generic: fever and extremely tender, swollen lymph nodes—known as “buboes”—usually emerging within two to six days of infection. According to the CDC, these lumps appear most frequently in the groin, armpit, or neck, which, if nothing else, is at least distinct enough to separate the experience from a garden-variety cold.

Old Fears, New Protocols

There’s a certain dark irony in the fact that centuries after the Black Death reshaped the course of European history, the modern preventative message sounds suspiciously familiar: avoid contact with sick wildlife, don’t pet random rodents, and, if you start sporting alarming lumps, call your doctor promptly. Public health officials in Coconino County advise anyone feeling seriously ill with a possibly contagious disease to mask up immediately before heading to the emergency room—a carryover from COVID-19 precautions that now applies to everything from influenza to, evidently, the plague.

NBC News highlights that the hospital reminded the public to clearly state their symptoms upon arrival to help prevent further disease spread, underscoring that modern protocols can turn a potential outbreak into a manageable event. As previously reported by the outlet, similar messaging has accompanied various disease outbreaks in recent years, suggesting a growing institutional memory for unexpected microbial flashbacks.

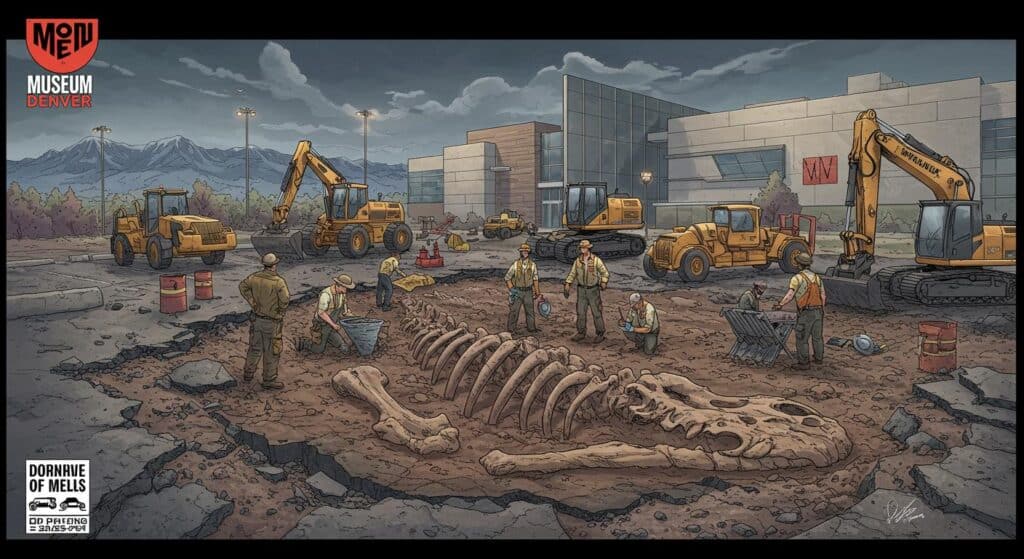

When Yesterday Sneaks Into Today

So, what to make of it all? Bubonic plague’s infrequent but persistent appearances in the American Southwest serve as a strange reminder that history’s greatest villains rarely disappear entirely—they just lurk, waiting for the next prairie dog or the next unlucky human to cross their path. While the comforts of antibiotics and rapid diagnostics have dramatically changed the survival odds, there’s something undeniably surreal about a medieval horror showing up in an Arizona ER.

Does the presence of plague in 2025 mean it’s time to dust off the bell-topped hats and panic anew? Not quite. But it does make you wonder: how many of history’s strangest chapters might still have an encore or two left? Nature, as always, keeps its old scripts handy—just in case.