When government science projects stray into the realm of the spectacularly weird, they sometimes land squarely in my wheelhouse. Breeding billions of flies and deploying them via airplane over two countries? That’s not a fever dream, but the latest—and, frankly, thoroughly practical—plan to stop a flesh-eating parasite from making a comeback. In a recent CBS News report, officials outlined the battle plan against the New World screwworm fly—a creature with such grim credentials, its scientific name Cochliomyia hominivorax translates, ominously, to “man-eater.”

The Return of the Flesh-Eating Fly

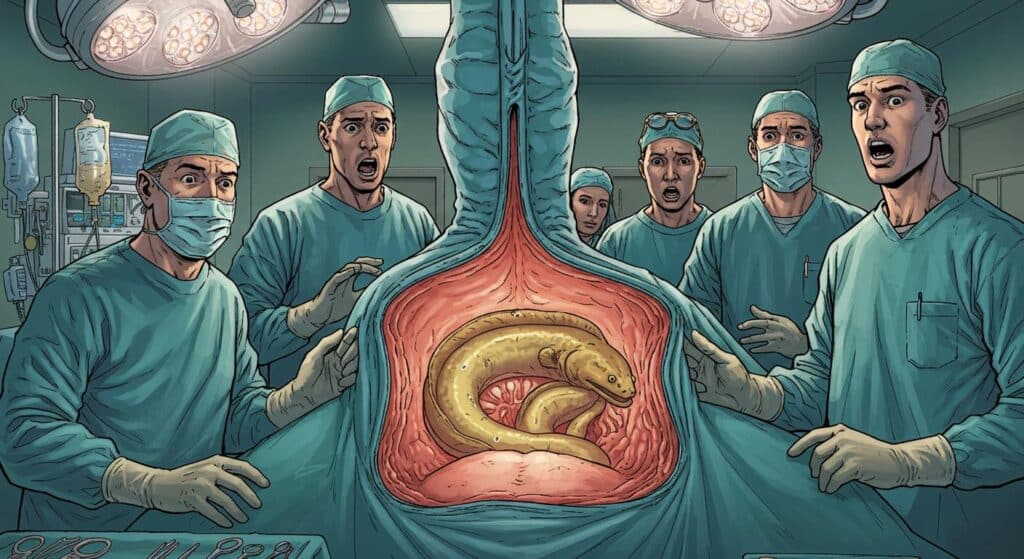

The problem isn’t just science fiction fodder. As described in CBS News, the New World screwworm is one of the rare parasites to enjoy fresh, not decaying, flesh. Females deposit eggs in wounds or exposed tissue of livestock, wildlife, even household pets, and in rare instances, humans. The resulting maggots burrow in and feast, with fatal consequences unless treated. Longtime ranchers, like Don Hineman, reminisced about infestations in cattle as “smelling nasty—like rotting meat,” an experience that apparently takes awhile to fade from memory.

For the beef industry, it’s more than just an olfactory offense; Michael Bailey, president elect of the American Veterinary Medicine Association, explained that a thousand-pound steer could die in under two weeks if untreated. It’s no wonder the reappearance of these flies in southern Mexico late last year lit a fire under U.S. agriculture officials.

Science vs. Maggot

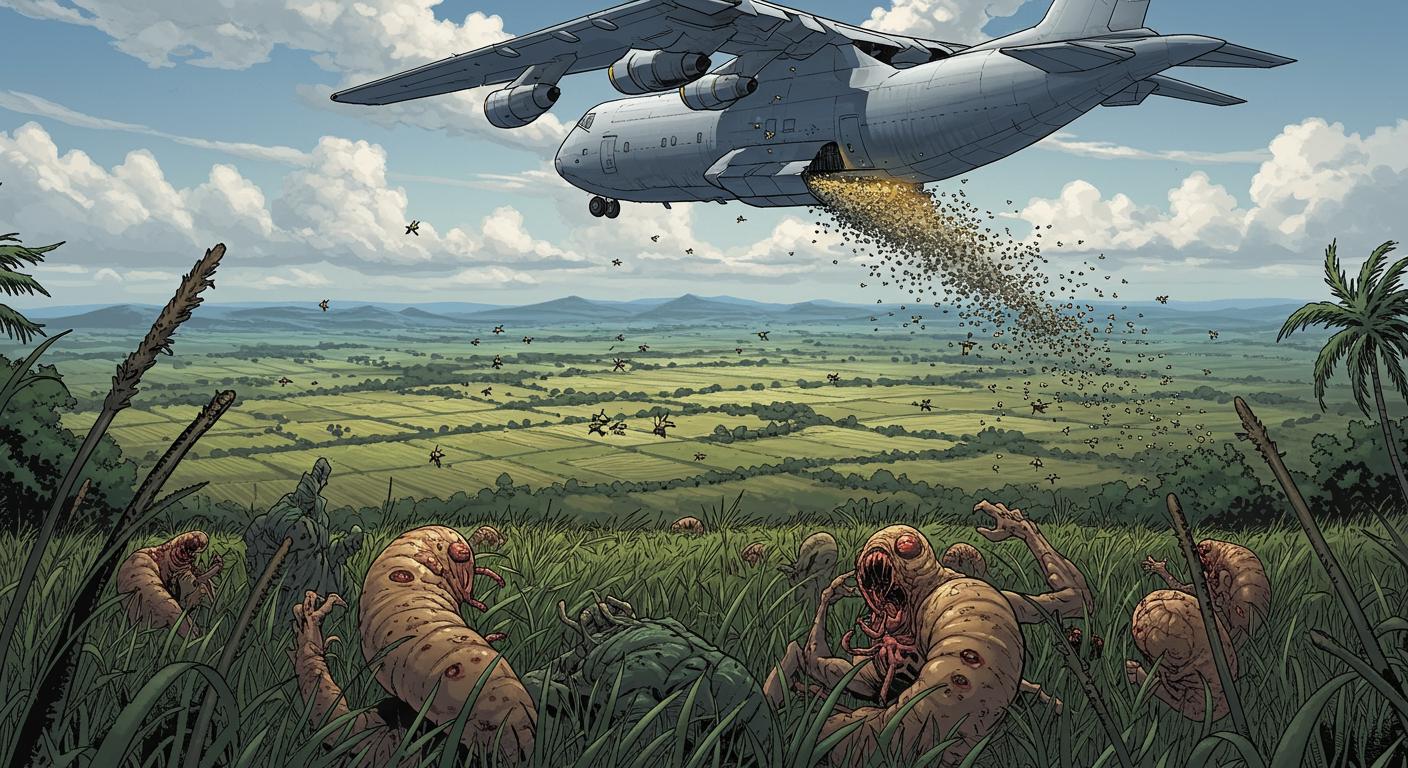

Rather than reach for a chemical sledgehammer, the plan flips the insect’s biology against itself. The government breeds sterile male screwworm flies, hitting them with just enough radiation to render them incapable of fathering larvae. These duds are then released from aircraft in overwhelming numbers. When wild females—who, per the USDA, mate just once in their short lifespans—choose a sterile partner, the resulting clutch of eggs never hatches. Over time, the population tanks. This strategy, cited by University of Florida’s Edwin Burgess as one of the USDA’s “crowning achievements,” proved so successful decades ago that the pest was all but eradicated north of Panama.

According to CBS News, the U.S. and Mexico released more than 94 billion sterile flies between 1962 and 1975, herding the screwworm to Panama. With its return to Mexico, an even larger operation is now in motion: the USDA wants to ramp up breeding to at least 400 million flies each week, establishing new facilities in southern Texas and southern Mexico. Budgets for these bio-barricades aren’t trivial—$8.5 million for a Texas distribution hub, $21 million to adapt a Mexican breeding facility from fruit flies to screwworms—all, presumably, money well spent if it keeps a flesh-eating parasite on the wrong side of the border.

The Curious World of Maggot Manufacture

Raising flies on an industrial scale turns out to be as much about culinary finesse as biological know-how. Cassandra Olds, interviewed by CBS News, noted that while setting up a giant fly colony is relatively straightforward, convincing the critters to lay eggs and nurturing their larvae to plump, adult readiness involves catering to their surprisingly specific tastes. Early fly factories preferred a diet of horse meat and honey, later transitioning to dried eggs, molasses, and, at the Panama site, powdered egg plus cattle blood plasma for the larvae. Even in the insect world, it seems, local ingredients matter.

Once larvae reach their maggot “pupal” phase, in nature they drop to the soil and tuck in just below the surface. In the factory, they’re sorted into trays of sawdust—possibly the only time you’ll see maggot and artisanal wood shavings in the same sentence. Security, as noted by Texas A&M University’s Sonja Swiger, remains a concern: a facility escape could, in theory, launch an outbreak—though the system is reportedly built to keep breeding adults tightly contained.

Bombs Away: Flies From the Sky

The act of releasing flies by air is, perhaps unsurprisingly, not without risk. CBS News details how, just last month, a plane distributing sterile flies crashed near the Mexico-Guatemala border, resulting in fatalities. The underlying method, however, has barely changed since the 1950s: light aircraft loaded with crates (sometimes using contraptions charmingly dubbed “Whiz Packers”) scatter their airborne passengers over target areas. In the words of Edwin Burgess, this approach stands out as a surprisingly robust and eco-friendly solution compared to drenching the countryside in insecticides.

An Unending Game of Pest Control

One lesson quietly lurking beneath all this effort is that triumphs over nature are rarely permanent. As CBS News recaps via various voices in the field, the last time screwworms were eradicated, the U.S. shut down its fly factories. Some now question the wisdom of shelving that capability, since even decisive victories in pest control can unravel over time—especially when warm weather and global livestock trade roll out a perpetual red carpet for hitchhiking parasites. It’s a gentle reminder (delivered, in this case, on tiny wings) that in the world of agricultural vigilance, vigilance may be the only guarantee.

Looking at this, you have to marvel at both the absurdity and elegance of combating a flesh-eating maggot by orchestrating fly-wide singles mixers on a continental scale. Does any other nation have a literal arsenal of irradiated insects on tap for such occasions? Or is this just another uniquely American answer to the fact that, sometimes, the truly bizarre is also an all-too-necessary reality check?