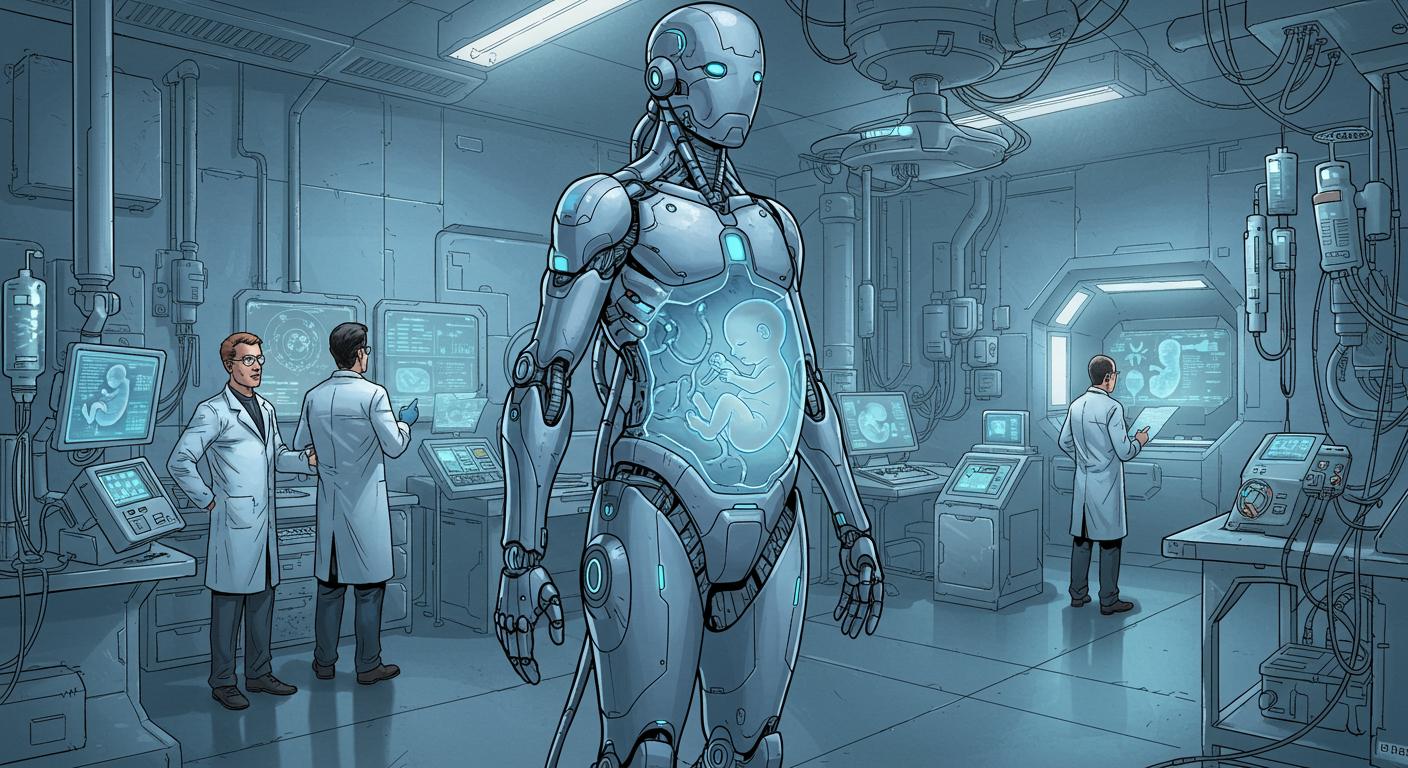

If you told me five years ago that “pregnancy robot” would trend on Chinese social media and not be the plot of a Netflix dystopian series, I would have asked you which speculative fiction conference you’d just returned from. But, as detailed in reporting by Ecns.cn and ChosunBiz, that’s where we are: a Chinese robotics company, Kaiwa Technology, has announced it will soon release the world’s first humanoid “pregnancy robot” equipped with an artificial womb. Its reported price tag—about 100,000 yuan, or $13,900—could make it the priciest “stork” outside of fairy tales, but a far cry from the costs typically associated with IVF or surrogacy.

Robotic Uterus, Insert Baby

So, what exactly is Kaiwa building? Zhang Qifeng, the company’s founder, describes the device as a humanoid robot with an abdominal “incubation pod” designed to replicate the entire journey from conception to delivery, complete with an artificial womb environment. Both Ecns.cn and ChosunBiz note that the robot’s artificial womb employs amniotic-like fluid and nutrient hoses to sustain fetal growth. Zhang maintains that this technology, at least in its current animal-testing incarnation, is approaching readiness for human gestation. His claims build directly on earlier milestones: ChosunBiz brings up the 2017 Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia experiment in which a lamb, born prematurely, survived for several weeks in a “biobag”—a transparent pouch filled with warm artificial amniotic fluid and nutrients supplied through tubing.

However, as described in the ChosunBiz report, that pioneering effort worked more as a high-tech incubator for prematurely born animals, not as a cradle for development from conception. For the pregnancy robot to truly deliver on its promise, Zhang would first need to bridge the sizable scientific gap between incubating a nearly-viable fetus and nurturing an embryo from fertilization onward—no small step, as Ecns.cn points out. Experts cited in Ecns.cn are quick to underline that replicating a full-term pregnancy demands far more: maternal hormones, immune crosstalk, and the intricate choreography of neurological and emotional development, none of which exist in a plastic pod. Questions linger about exactly how fertilization and initial embryo transfer would occur, and in the interviews highlighted in both outlets, Zhang doesn’t offer specifics.

Science Fiction Meets Real-World Questions

Whatever the scientific hurdles, news of the pregnancy robot spread like wildfire on Chinese social platforms. Ecns.cn reports that Weibo saw the topic rocket to the top of its trending list with over 100 million views by press time. Reactions captured by both outlets range from the ecstatic (“Women have finally been liberated!”) to the uneasy (“It is cruel for a fetus to be born without connection to a mother”). In ChosunBiz’s documentation of Douyin video comments, debates ran from concerns about ethical boundaries (“It completely violates human ethics”) to logistical questions (“Where do the eggs come from?”), with plenty of enthusiasm among those struggling with infertility: one user wrote, “I tried artificial insemination three times but failed all of them. Now I have a chance to have a baby.”

The optimism has context. ChosunBiz, citing a Lancet study reported within its coverage, points out that China’s infertility rate climbed from 11.9% in 2007 to 18% by 2020. Responding to this trend, local governments in cities like Beijing and Shanghai have broadened insurance coverage for IVF and related procedures. For many facing repeat IVF failures, the idea of a “robotic womb” conjures hope that technology will finally tilt the odds in their favor.

Yet, as Ecns.cn covers, critics are equally vocal. The lingering philosophical dilemmas are not so easily resolved. What exactly constitutes motherhood when the womb is metal and wires? If a robot’s pod substitutes for the warmth and hormonal symphony of a human pregnancy, can we claim the result is truly the same? And what will the absence of maternal-fetal bonding mean for the child—biologically, emotionally, ethically? Practical questions echo as well: Who provides the eggs and sperm, and how will the process be overseen? What comes next for the robot itself, post-delivery?

Utopia or the Ultimate Uncanny Valley?

Both reports note that inventor Zhang positions his technology as a response to shifting societal needs—solving issues not just of infertility, but of China’s declining birth rate and the ban on commercial surrogacy. In ChosunBiz’s interview, Zhang frames it as a tool for individuals who want children without marriage or pregnancy, sidestepping legal barriers.

Yet, as observed by Ecns.cn in a popular Weibo comment, another old obstacle remains: “The problem is not that we don’t want children, but the cost of raising them.” Parenting, it seems, defies easy mechanization.

As the debut of the pregnancy robot draws near, I find myself mulling not just over its technical plausibility or its legal status, but the quietly jarring weirdness of our technological ambitions. Should we want this future? What will family look like if robots, with eerily human shells, are entrusted with the earliest stages of life? And if we are building artificial versions of the most fundamental human experiences, are we ready for the surprises—good, bad, or simply stranger than science fiction—that might follow?

For now: the artificial womb has entered the chat. Whether we leave it on read is another question entirely.