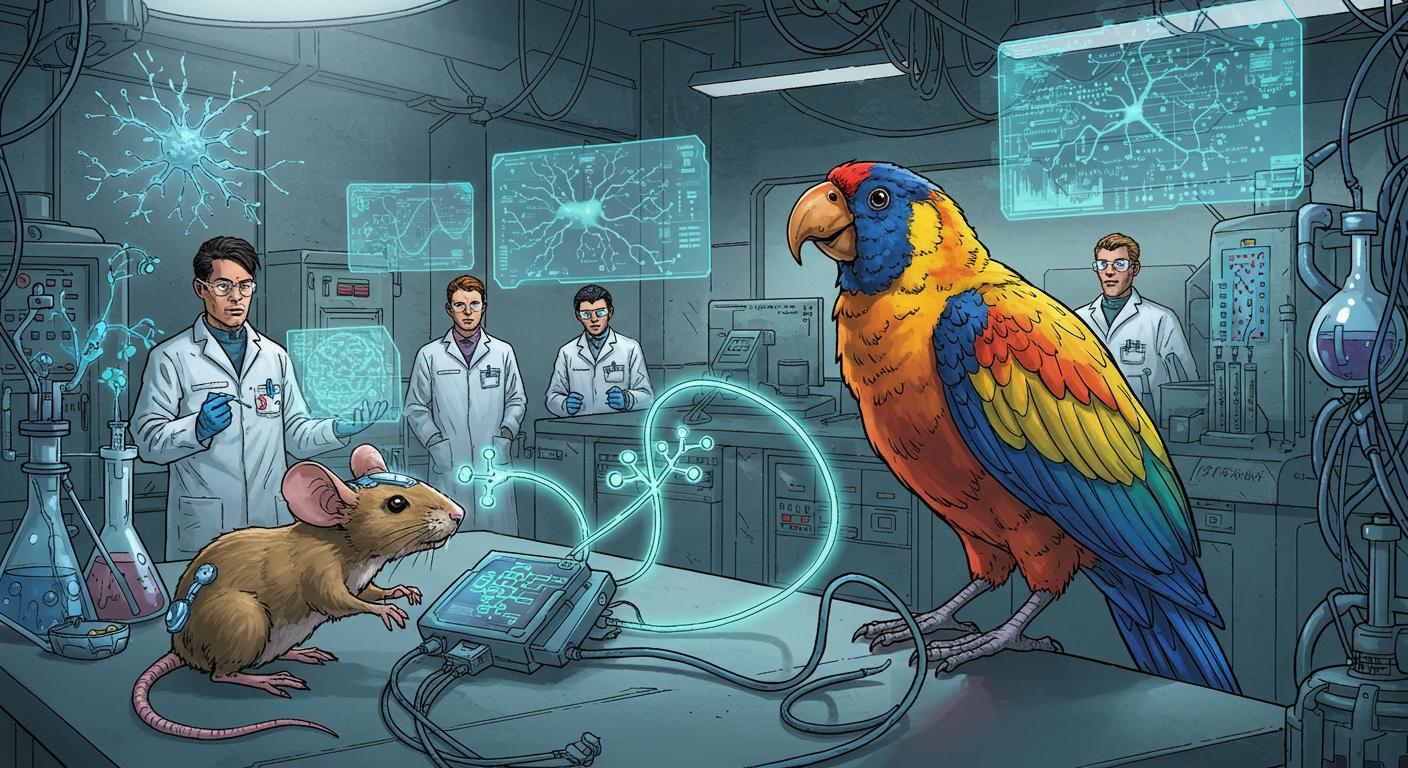

Sometimes, lurking in the genetic basement of a species, you find an odd, dusty box labeled “Do Not Open – Last Used 35 Million Years Ago.” This week, a research team in Japan went ahead and found out what happens if you open that box anyway. As reported by New Atlas on the world’s first behavior transplant, scientists at Nagoya University managed what they’re calling a “behavior transplant” between two different species of fruit fly. In less poetic terms, they got one animal to do something it had absolutely no business knowing how to do—by rewiring its brain at the genetic level.

Love Songs and Regurgitated Blobs

To properly appreciate the weirdness on display, let’s get acquainted with our winged subjects. Drosophila melanogaster is the classic fruit fly, a lab mainstay best known for its courtship rituals that involve sweet, sweet serenades. Males vibrate their wings, producing a (presumably romantic) song to woo a mate. On the other hand, its cousin Drosophila subobscura prefers a rather less melodic approach: males regurgitate a little food and present it to the female—a nuptial gift, if you will. (Chocolates and flowers look positively uninspired by comparison.)

Historically, each species stuck to its own script. But, as New Atlas chronicles, the Nagoya University researchers asked: what if you swapped a single genetic switch, just to see what would happen?

A Tiny Flip, A Mammoth Shift

It turns out, the answer is “a lot.” In a detail highlighted by New Atlas, the team zeroed in on a gene called Fruitless (Fru), a known heavy-hitter in the courtship department for fruit flies. Both species have the Fru gene, but its “love language” code is apparently context-dependent. In D. melanogaster, it controls the impulse to sing; in D. subobscura, it’s in charge of orchestrating the food regurgitation ritual.

By using genetic engineering and a dash of what is essentially brain wiring wizardry, the scientists managed to “flick on” the Fru gene in a cluster of insulin-producing neurons in D. melanogaster. These neurons, dormant for millions of years with respect to gifting behaviors, suddenly sprang to life with neural connections redirecting to the courtship center. The upshot? The typically singing males started offering up food blobs—an act none of their ancestors would have ever dreamed up (or wished upon a potential mate).

Notably, this wasn’t an act of painstaking training or fly mentorship. The subjects performed the new behavior without social exposure or trial and error, suggesting the instructions were there all along—just never unlocked, as described by New Atlas.

What Evolution Left Sitting in the Attic

When lead researcher Ryoya Tanaka explained to New Atlas, “When we activated the fru gene in insulin-producing neurons of singing flies to produce FruM proteins, the cells grew long neural projections and connected to the courtship center in the brain, creating new brain circuits that produce gift-giving behavior in D. melanogaster for the first time,” he wasn’t just describing a technical flourish: he was outlining a blueprint for dormant behaviors locked away by evolution. As New Atlas carefully documents, this means the emergence of new species behaviors may not hinge on adding new brain bits, but on simple rewiring—a genetic switch and, poof, a new skillset.

Co-author Yusuke Hara is cited in the same report as underscoring that evolutionary changes can shuffle existing neurons rather than inventing new ones. It’s a refreshingly minimal approach on nature’s part—appropriately thrifty, almost like evolution is clipping coupons.

Dormant Skills and Speculative Possibilities

Naturally, the potential implications ripple out in all directions, some more sci-fi than others. If one gene can flip hardwired, entirely foreign behaviors on in fruit flies, what odd scripts might be lurking, undetected, in the unused neighborhoods of our own genetic code? No one is suggesting we’re close to coaxing ancient instincts—or forgotten dance crazes—out of Homo sapiens just yet. But the principle is both unsettling and kind of thrilling.

New Atlas points out fruit flies share about 60% of their genetic makeup with humans, and that three-quarters of human genetic diseases have a counterpart in flies. Not for nothing have fruit flies delivered six Nobel Prizes’ worth of breakthroughs. Yet, the leap from gifting regurgitated snacks to new human behaviors remains towering. Still, it raises an eyebrow: what else is quietly sitting in our genomes, locked up by evolutionary deadbolts waiting for the right molecular skeleton key?

Evolution by Edit: Rewiring the Big Picture

Beyond insect romance, the experiment offers a lens through which to view how evolution might work its magic—less by clumsy trial and error, more by subtle reconfiguration and remixing. As New Atlas also notes, in 2024, the most detailed neuronal map of the fly brain was completed, providing a literal roadmap for this sort of brain hacking. Maybe the next behavioral revolution is already hiding in the background code, awaiting a scientist persistent (or curious) enough to hit “activate.”

So, as we contemplate the fruit fly transformed into an unexpected suitor, a question hovers: if an ancient behavior can be dusted off so easily in a fly, are there ancestral quirks buried in all of us, only a switch-flip away? And if so, how many of our “hardwired” instincts are simply the ones someone—or something—got to before we did? The evolutionary junk drawer just got a lot more interesting.