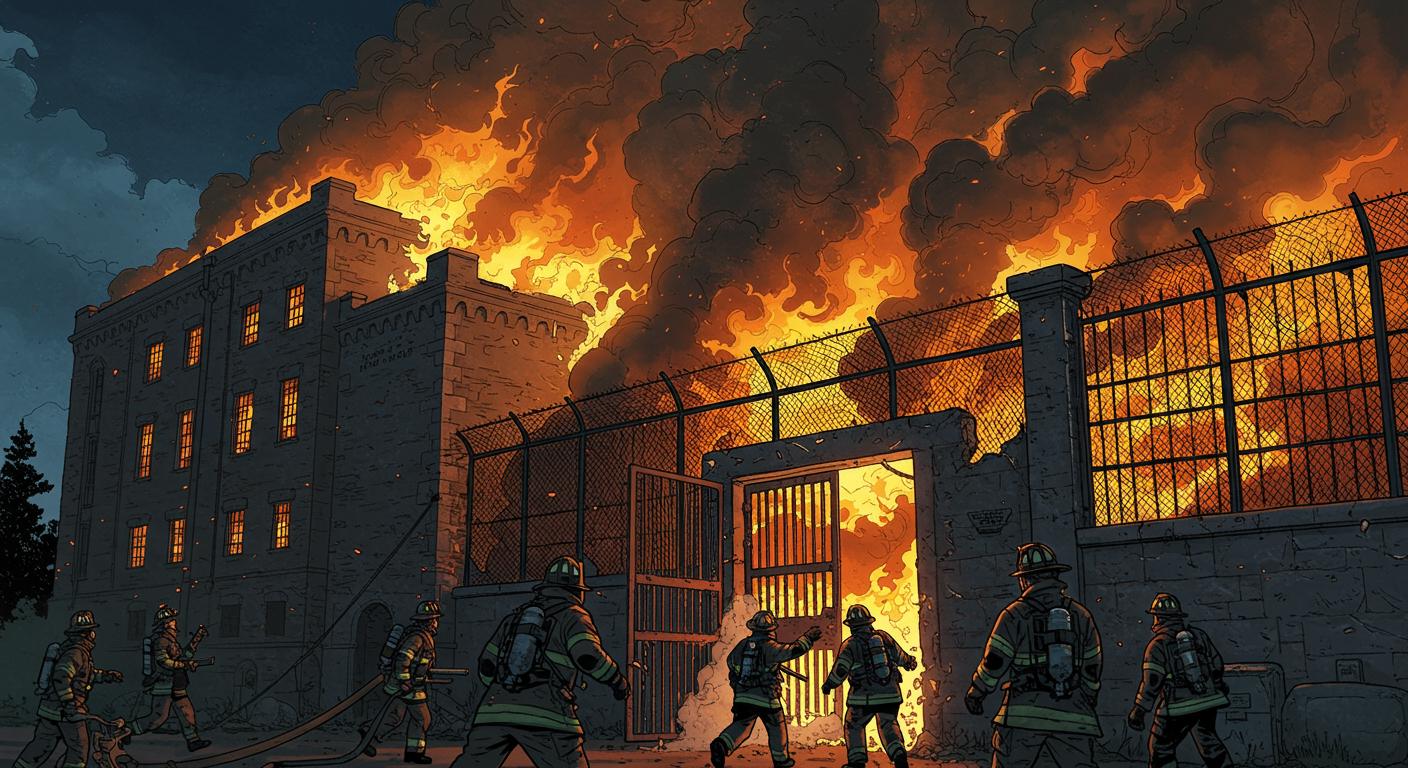

If you’ve ever found yourself pondering the reliability of old locks, be grateful you weren’t on duty with Kingston Fire & Rescue at 5 a.m. Saturday. Described by Global News as a “challenging” morning, crews responding to a blaze in Kingston Penitentiary’s Cell Block 1 were handed keys and codes, only to discover that—much like those souvenir novelty keys you pick up at historic prisons—none of them worked. Faced with a burning 19th-century fortress and recalcitrant security measures, it’s little wonder that, as The Whig-Standard later summarized, firefighters opted for brute force: they broke in.

The Prison, The Problem, and the Prying

According to statements shared in Global News, Deputy Chief of Operations Don Carter admitted with remarkable deadpan that “access was challenging as keys and codes KFR were provided did not work.” This was perhaps not the nostalgic tour the crew anticipated; instead, it was a literal lock-in with the past, culminating in a forced entry through the garage door. Centuries of formidable security—a system once designed to keep Canada’s most notorious criminals inside—apparently proved equally effective at keeping out the folks wielding firehoses. You’d think after 190 years, they’d have at least one working key, but perhaps modern firefighting calls for a crowbar just as often as a codebook.

The Whig-Standard’s account notes the initial fire originated in the roof area of Cell Block 1. Firefighters arrived swiftly and tried to contain the flames with an aerial apparatus to prevent spread to the thick exterior prison walls. Notably, after repeated (and fruitless) attempts to access the interior using keys, crews had, as the outlet puts it, “no choice but to gain entry by force.” Once finally inside, the team brought the fire under control by 5:15 a.m. and wrapped up operations about an hour later—though fire prevention staff lingered, presumably armed with both hoses and a newfound skepticism toward historic locking mechanisms.

There’s a satisfying irony here: for more than 170 years, Kingston Pen was famed for being impenetrable. Now, in its twilight years as a museum and backdrop for prestige TV, the only thing successfully breaking in is a squad of firefighters, garage door in tow. Would it be too poetic to say the building remains undefeated?

When Locks Outlast Their Purpose

Beyond the technical comedy of errors, the incident offers a strange window into what happens when history’s artifacts outlive their original context. Global News points out that Kingston Penitentiary hasn’t housed inmates since 2013, but is kept in working order as a tourist destination and filming location—one with the sort of locks that, apparently, really commit to the bit.

When the building shifted from notorious prison to heritage centerpiece, perhaps no one updated the emergency playbook—or maybe everyone just assumed at least one old key would work. For visitors, the mishap meant a cancelled tour; for one firefighter, a rough start to the weekend, having required treatment for heat exhaustion right there at the scene, both sources confirm.

Carter told Global News that $50,000 to $100,000 in damages is the present estimate. The source of the fire remains undetermined, with Corrections Canada Investigators now overseeing matters. The Whig-Standard also notes fire prevention staff remained at the scene, underscoring just how cautious the authorities are, given the building’s storied—and slightly stubborn—past.

One has to wonder: how many buildings actually become more secure when they close to the public? And what does it say about our fascination with historic sites when even rescue efforts turn into a kind of performance, starring the world’s most exasperating set of keys?

Reflections from Behind (or is it Outside?) the Bars

One almost imagines Kingston Pen itself sighing in satisfaction—a fortress still holding the line, whatever the century, refusing to yield to both inmates in the 20th and firefighters in the 21st. There’s an odd poetry to firefighters having to break into a penitentiary to do their job—especially one famous for its impenetrability. As Global News highlights, the roster of infamous former residents—from Paul Bernardo to Clifford Olson—may be gone, but the building itself still makes a show of being impossible to access.

For fans of the bizarre and the beautifully ironic, this story delivers in understated spades. Firefighters train for distant wildfires and high-rise infernos, yet sometimes the biggest battle is with century-old hardware. Doors that open easily for tourists, barring rescue crews instead. Should future training include locksmithing? Or do we simply tip our hats to Kingston Pen for a final, stubborn flourish?

No one was seriously injured, the damage is being tallied, and the historic cellblock will likely open once again to camera crews, tourists, and the architecturally curious. Yet, there’s a fitting lesson here: sometimes, the thing designed to keep people in is just as effective at keeping help out. When a building built for security outlasts its wardens, is it still a prison—or just showing off?