Some inventions sprawl out of decades of planning, while others—like this one—seem dropped onto our laps by an unusually inventive universe. According to recent coverage from Popular Science, News Medical, and Stubx.info, scientists have revealed a genuinely strange upgrade in our ongoing mosquito wars: nitisinone, a prescription drug, can turn your blood into a mosquito death sentence and kill even the craftiest, insecticide-resistant biters. We’ve spent centuries as delicious (if unwilling) participants in mosquito buffets. Now—who knew?—science has handed us a chance to become the main course no skeeter survives.

When Therapy Turns to Pest Control

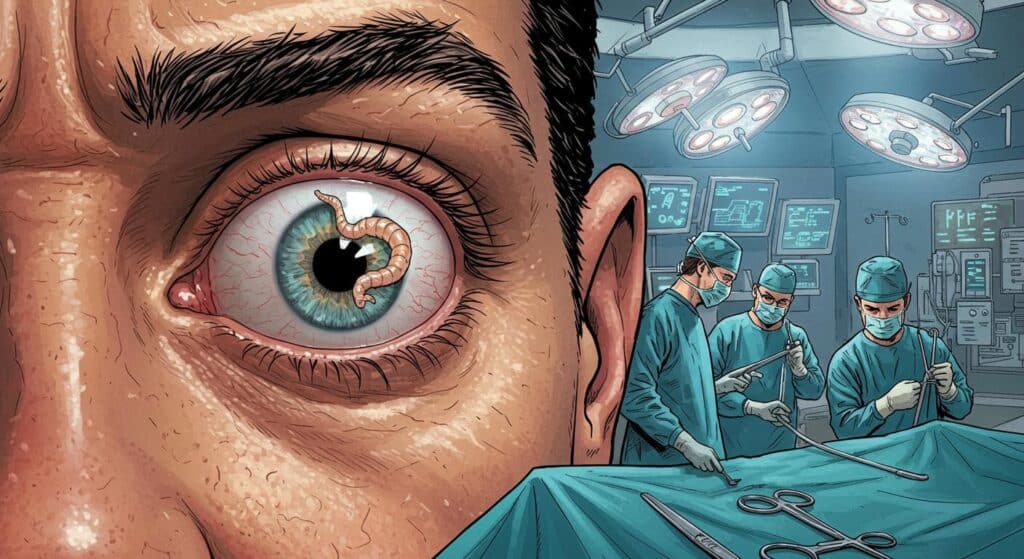

Nitisinone wasn’t engineered for this. As reported in both Popular Science and News Medical, its story begins as an herbicide inspired by a naturally occurring toxin in the Australian bottlebrush plant. The compound’s knack for halting tyrosine metabolism (a nonessential amino acid with crucial hormone-handling duties) soon led researchers to successfully test it as a treatment for rare genetic diseases like tyrosinemia type I and alkaptonuria. By 2002, the FDA had approved nitisinone for human use for these purposes.

But as Popular Science lays out in detail, things took a darkly amusing turn when researchers asked: If it fiddles so effectively with human metabolism, what would a mosquito make of blood tinged with nitisinone? Turns out, nothing good. In findings summarized by News Medical, mosquitoes that took a bite out of humans on nitisinone promptly died within hours—no matter the dose, the drug effectively sabotaged their ability to digest the gluttonous protein load drawn from blood, leaving them with digestive system gridlock and a ticket to the hereafter.

One particularly memorable line from lead author Zachary Stavrou-Dowd, cited by News Medical, explains the process neatly: nitisinone “acts to clog up the mosquito digestive system. When a mosquito gorges on your arm, that blood contains a massive protein load. What we have shown here is that we can turn that key trait against them. The mosquito can’t digest the blood; it becomes overloaded by its own meal; it dies.”

Footloose—and Flatlining

The pill’s effect isn’t just limited to those willing to serve as blood bait. The Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine’s latest work, described in News Medical and echoed by Stubx.info, highlights an even more peculiar outcome: mosquitoes were killed after merely landing on surfaces treated with nitisinone. No need to line up for a bite—just land, and their feet soak up enough of the drug to trigger paralysis and eventual death. Across multiple species, including bringers of malaria, dengue, and Zika, the result was the same: darkened bodies and an early end to their buzzing errands.

Despite scientists’ efforts, a minor mystery remains. As relayed in News Medical, researchers are unsure why nitisinone so readily seeps through mosquito feet or why similar (and seemingly related) compounds fail to do the trick. Lee Haines, senior author and Honorary Research Fellow at LSTM, is quoted as saying, “This project proved how important it is to think outside the box … It is going to be exciting to solve this mystery!”

Is there something uniquely absorbent about mosquito tarsi, or have we just stumbled onto a chemical Achilles’ heel—literally? For now, the oddness remains wonderfully unresolved.

The Insecticide Resistance Arms Race Hits a Wall

Of all the facts in these reports, perhaps the most satisfying is nitisinone’s ability to finally outfox insecticide-resistant mosquitoes. According to WHO data cited in both Popular Science and Stubx.info, these resilient mosquitoes have spread to more than 90 percent of malaria-endemic countries, with some studies suggesting up to 30 percent of the global mosquito population now laughs off our best chemical defenses. For years, bed nets and household sprays have grown less trustworthy—not because we’ve applied them badly, but because evolution moves fast when survival is on the line.

Now, described in the study published in Parasites & Vectors and relayed by News Medical, nitisinone’s entirely new mode of action—targeting blood digestion rather than the usual neural pathways—means its mosquitocidal magic isn’t just a repeat of the old tricks. Haines emphasized to News Medical, “Working with a drug like nitisinone, and its versatility, bodes well for creating new products to combat mosquitoes. The fact that it effectively kills insecticide-resistant mosquitoes could be a game-changer in areas where resistance to current insecticides is causing public health interventions to fail.” The outlet also notes that nitisinone acted reliably across Anopheles, Aedes, and Culex mosquitoes—leaving barely any room for escape, regardless of prior insecticide resistance.

From Bed Net to Prescription Bottle: Unorthodox Futures

The creative applications here seem almost endless—or at the very least, a little surreal. As discussed in both Popular Science and Stubx.info, household items like window screens, bed nets, or other mosquito-skirmish interfaces could be coated in a nitisinone solution. Mosquitoes absorb the poison on contact, and public health campaigns get an alternative to ever-stronger (and environmentally risky) insecticides.

But what of the human-as-insecticide idea? Society probably isn’t prepared for a bonanza of off-label, mosquito-poisoning prescriptions; after all, nitisinone still carries its own medical considerations and is primarily intended for patients dealing with those rare tyrosine-digesting disorders. Patient safety—both for intended recipients and the wider population—remains a core concern, a point echoed in the reporting from News Medical.

That said, the concept feels like something out of speculative fiction: people literally transforming themselves into walking bug zappers, their blood an unexpected defense. What would family picnics become if everyone showed up dosed and toxic? Would this finally settle the age-old question of why certain people seem to attract more mosquito bites—could our future solution be as simple as reaching for a capsule instead of bug spray?

Imagination, Bizarre Solutions, and Next Steps

It’s worth noting, as both Popular Science and Stubx.info do, that this isn’t our only ingenious scheme for mosquito control. There are genetically engineered mosquitoes that collapse local populations, tropical regions seeded with “elephant mosquitoes” that prey on their kin, and even drone-dropped pods of larval assassins in Hawaii. Yet few strategies so thoroughly invert the table as nitisinone does: instead of poisoning the environment or the insects directly, we quietly make ourselves unpalatable—or, viewed from the mosquito’s perspective, downright hazardous.

Still, some questions linger, and researchers seem almost delighted to follow these new trails. Will nitisinone provide an answer to other insect pests that plague humans? Are there similar compounds hiding in plain sight, just waiting to be repurposed by a researcher having a particularly inspired afternoon? And will we ever quite know why this compound, and not its chemical cousins, takes such gleeful advantage of mosquito physiology?

One can’t help picturing the endless summer nights ahead: no longer a time for itching, slapping, or frantic swatting, but instead a low-key chemist’s victory march. How strange—and, maybe, oddly satisfying—it would be if the best solution to mosquitoes wasn’t outside our bodies, but in our veins. Does victory taste sweeter when you are, in fact, the bait? The science isn’t settled, but the possibilities, much like mosquitos in July, seem to be everywhere.