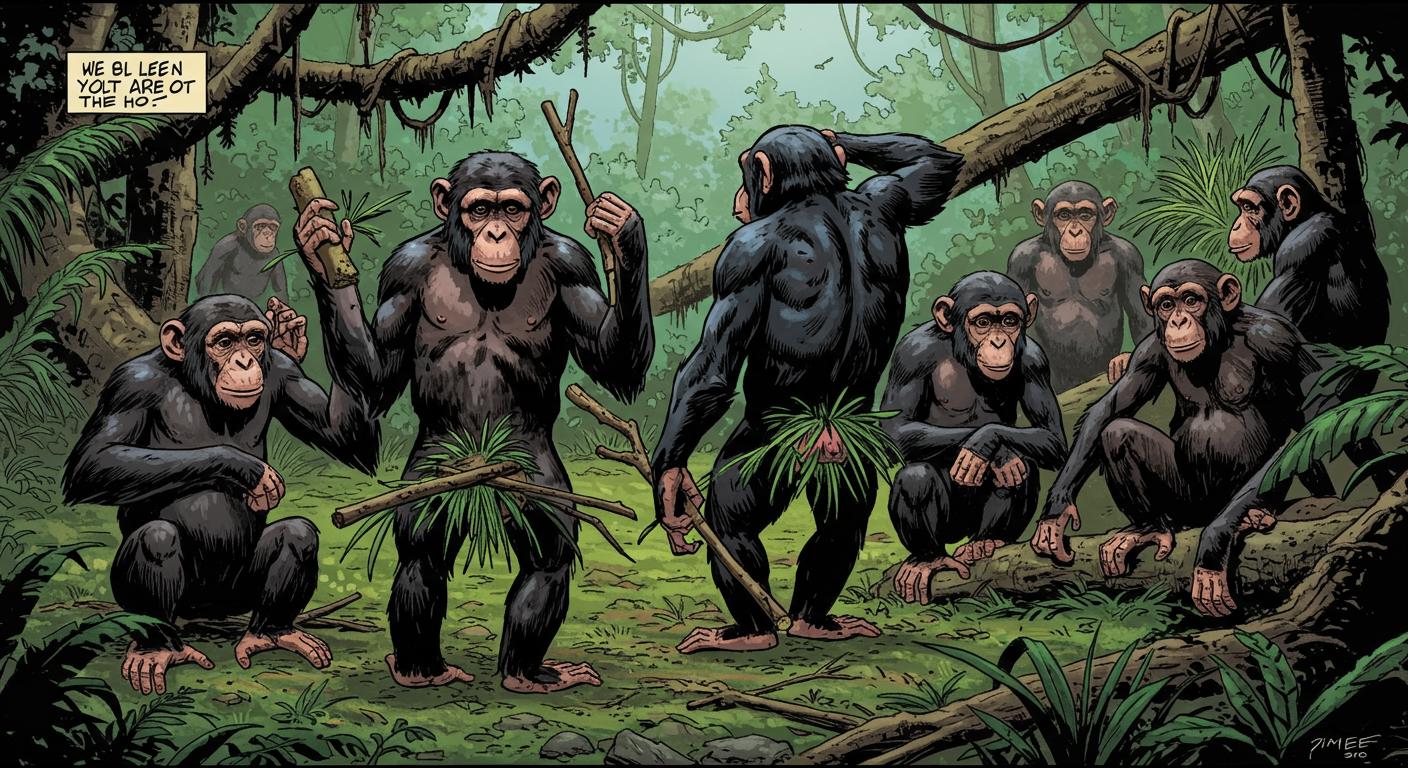

If you thought humanity had the monopoly on pointless trends and questionable accessories, allow me to introduce you to the latest wave of innovation from our primate cousins: grass-in-the-butt chic. This is not a metaphor. Chimpanzees at the Chimfunshi Wildlife Orphanage in Zambia are now accessorizing themselves by sticking blades of grass—or occasionally sticks—into their ears and, yes, their rectums, as described in Live Science. The resulting look is hard to improve upon: blades dramatically snagged on the side of the head or trailing from the rear, dangling for maximum effect.

An Old Fad With a Cheeky Twist

This flair for herbal accessorizing isn’t entirely original. Live Science recounts how, back in 2010, a chimp named Julie began wearing a single blade of grass in her ear, turning an ordinary plant into the must-have item among her troop. Remarkably, when Julie died in 2013, a few close companions—and her own son—kept the look alive. Years later and with no overlap between groups, another troop at the sanctuary, with its own cast of characters, spontaneously revived the trend, but with a twist destined to get attention on any runway: they started experimenting with where grass could be stashed, introducing the “grass-in-butt” variation.

Researchers at the site, as cited in both Live Science and CBC, were taken aback. Jake Brooker, a psychologist and great apes researcher at Durham University, told CBC that his team was first surprised to see the ear behavior resurface, but even more so when they observed the new placement—something no chimp had previously attempted. One male, Juma, led this innovation, and almost immediately, most of his groupmates were sporting their own botanical embellishments. Whether in ear or rectum, the trend spread like wildfire.

How to Learn Useless Tricks: The Cultural Pipeline

Pinning down the origins of these fads, the new study published in the journal Behaviour points to a distinctly human influence. Researchers noticed that only the groups with certain human caretakers—caretakers who sometimes put grass or matchsticks in their own ears for cleaning—picked up the trend. Edwin van Leeuwen, the study’s lead author, explains that the chimps, “copied it from a human who was walking by the enclosure, or one of the caregivers who was just going about their daily lives,” as summed up in both CBC and Live Science coverage. However, the creative leap from ear to butt appears to be the chimps’ own twist on the borrowed idea.

Interestingly, VICE, which reviewed the same study and spoke with van Leeuwen, highlights how having extra leisure time in captivity may have nudged these primates toward creative displays like this. With food guaranteed and fewer survival tasks, some captive chimps seem to fill their social calendars inventing fads—they might be, for lack of a better term, “making their own fun” out of whatever’s lying around.

Social Signals, Butt Edition

The question arises: Why the butt? As CBC notes, primatologist Julie Teichroeb suggests there could be a social—or even sexual—element to the new trend. Female chimps already display conspicuous swellings on their rear ends as a mating signal, and everyone apparently spends a good deal of time appraising each other’s behinds. Is grass just today’s equivalent of a daring new hair color, designed to catch the eye? Brooker drew a parallel to human ear-piercing, describing the chimps’ initial discomfort as they learned the behavior, but noting they eventually wore their accessories unbothered—a parallel to the things humans put up with for a shred of style.

In the broader context, as Live Science notes, similar oddball fashions pop up across social animal species. Orcas in the Northwest Pacific have been seen parading around with dead salmon on their heads, while “trash parrots” in Australia have apparently established their own drinking rituals. These behaviors, whether fleeting or persistent, seem to spring up independently and occasionally resurface after years of dormancy—a kind of animal-world echo of recycled skinny jeans or surprise return of the bucket hat.

Social Belonging, Mimicry, and the Universal Fad

Delving into the study’s interpretation, VICE adds another layer: copying the behavior, researchers argue, is a visible sign of recognition or liking, helping to strengthen social bonds and create a sense of belonging. “By copying someone else’s behaviour, you show that you notice and maybe even like that individual,” van Leeuwen told the outlet. The ritual is pointless—at least in terms of survival or health benefit—but packed with social symbolism. The same urge fueling human trends, from the communal madness of pet rocks to illogical TikTok challenges, pulses through chimpanzee communities, too.

All three outlets agree that with food and safety provided, the sanctuary’s chimps have the luxury of experimenting with fads “just for the heck of it.” And they’re not alone. As VICE notes, in Guinea-Bissau wild chimps have been caught drinking mildly fermented fruit, possibly inventing “happy hour” far from human influence—yet another reminder that fun, belonging, and a taste for the bizarre aren’t uniquely human indulgences.

Kinship in Pointlessness

The longer you stare at these stories, the fuzzier the line between human and animal cultures becomes. As Teichroeb reflected to CBC, “Learning that animals have these kinds of same, pointless little behaviours that become fads and become viral, I think it really shows how closely related we are to them, how much kinship we actually share.”

One can hardly miss the irony: we marvel at the absurdity of chimps decorating their behinds with lawn clippings, while being only a few years removed from our own collective obsession with things like fidget spinners and “planking” photographs. What’s next for the fashion-forward chimp crowd—leaf hats? Decorative sticks in the nose? One wonders what new twist will catch on at the next rainy season.

But the real revelation is this: sometimes, the things that seem perfectly pointless say the most about us—whichever side of the glass we’re on. In the end, whether you’re wearing grass, jewelry, or just a questionable new jacket, maybe the most fundamental urge is to be noticed, and to belong, even if it involves putting grass literally where the sun doesn’t shine. That, it turns out, might be the most primate thing of all.