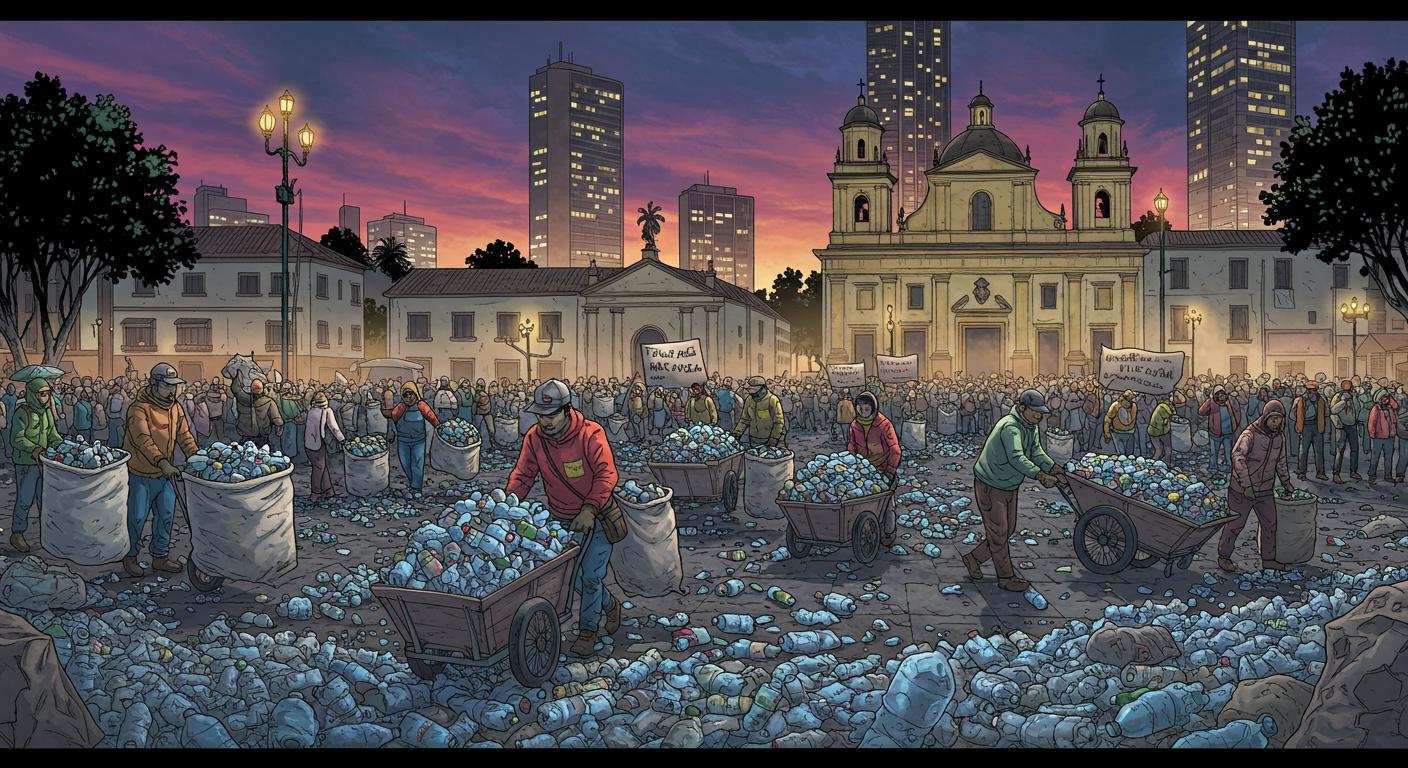

Sometimes, all it takes is a pile of empty bottles to lay bare how systems can run on the backs (and carts) of people everyone else would rather not see. That’s exactly the tableau that unfolded in the heart of Bogotá this week, as about 100 Colombian waste pickers—armed with 15 tons of recyclable goods—transformed the city’s Plaza Bolívar into a sea of discarded plastic and cardboard. NewsNation reports that this wasn’t your standard demonstration: instead of waving placards, some protestors sprawled on mounds of trash and pretended to swim through the refuse, making their point impossible to overlook.

A Spectacle in Plaza Bolívar

Organized by 14 waste picker associations, the protest commandeered Bogotá’s most emblematic square. According to information highlighted by NewsNation, the city’s approximately 20,000 waste pickers—often seen hauling heavy carts through neighborhoods, salvaging what’s left after garbage trucks pass—work outside the formal system, extracting recyclable materials largely unnoticed by the public. On this occasion, their decision to occupy the city’s symbolic center suggested just how urgent their concerns have become.

Within a single demonstration, the issues were made visible—literally and metaphorically. Footage reviewed by the outlet shows participants lying among plastic bottles and cardboard, the detritus forming an impromptu “blanket” over the famous plaza. Some “swam” theatrically through the plastics, an image that lands somewhere between performance art and practical politics.

Sliding Scale: Wages Dropping, Competition Rising

Details from the AP indicate that the root of the protest lies in a rapid drop in income. Jorge Ospina, president of the ARAUS waste pickers association, explained that over just two months, the price paid by recycling plants for collected plastic slid from roughly 75 U.S. cents per kilo to just 50. This decrease has trickled down rapidly—waste pickers dropping materials at the ARAUS warehouse now receive only about 25 cents per kilo for their efforts. Ospina suggested this plunge could be traced, at least partially, to an influx of cheap new plastic imported from abroad, notably China.

The margins were never generous to begin with. As discussed in the same report, most waste pickers fall short of Colombia’s $350 monthly minimum wage. Throw in a surge of Venezuelan migrants entering the informal recycling trade in cities like Bogotá and Medellin and, suddenly, a tough job becomes a competitive scramble with even thinner rewards. It’s a precarious balance: if the prices dip much further, Ospina warned, many may abandon the work altogether—leaving the city’s landfills to “overflow.”

The “Swimming” Metaphor

Nohra Padilla, head of Colombia’s National Association of Waste Pickers, offered a simple, pointed message: “Colombians and their government need to realize that without our work landfills would be saturated.” This detail, mentioned by NewsNation, cuts to the core of the paradox. Colombia’s constitution specifically protects waste pickers, granting them priority over corporate contractors and even mandating that municipal governments pay associations monthly based on tonnage. Yet the actual payments and livelihoods, as the outlet documents, remain hostage to volatile markets and sporadic enforcement.

In a detail previously cited, most pickers work independently, pulling carts and targeting recyclables left out by municipal garbage contractors, who tend to focus only on organic and nonrecyclable trash. Their compensation swings daily with the commodity market and city policy—a system where the essential is also the most precarious.

A Blanket Statement?

So what lingers after a public square is carpeted in 15 tons of trash? The protest in Plaza Bolívar functioned as a kind of civic Rorschach: Is it an act of desperation or an ingenious way to make the invisible visible for a day? The demonstration’s organizers laid out the warning plainly—without fair pay, the city’s informal recycling system may simply unravel, and the mess will, quite literally, be left for everyone else.

Maybe it takes a surreal scene—people swimming through discarded bottles in front of government buildings—to force a fleeting moment of recognition. Are such stark spectacles the only way underappreciated workers can seize the spotlight, however briefly? Or, as so often happens, will the square be swept clean by morning, with little left but a faint memory and the same old economics slowly piling up just out of sight?

Odd, effective, and just a little bit poetic: sometimes, the best way to make a point is to wrap the city in its own waste and dare someone—anyone—to look away.