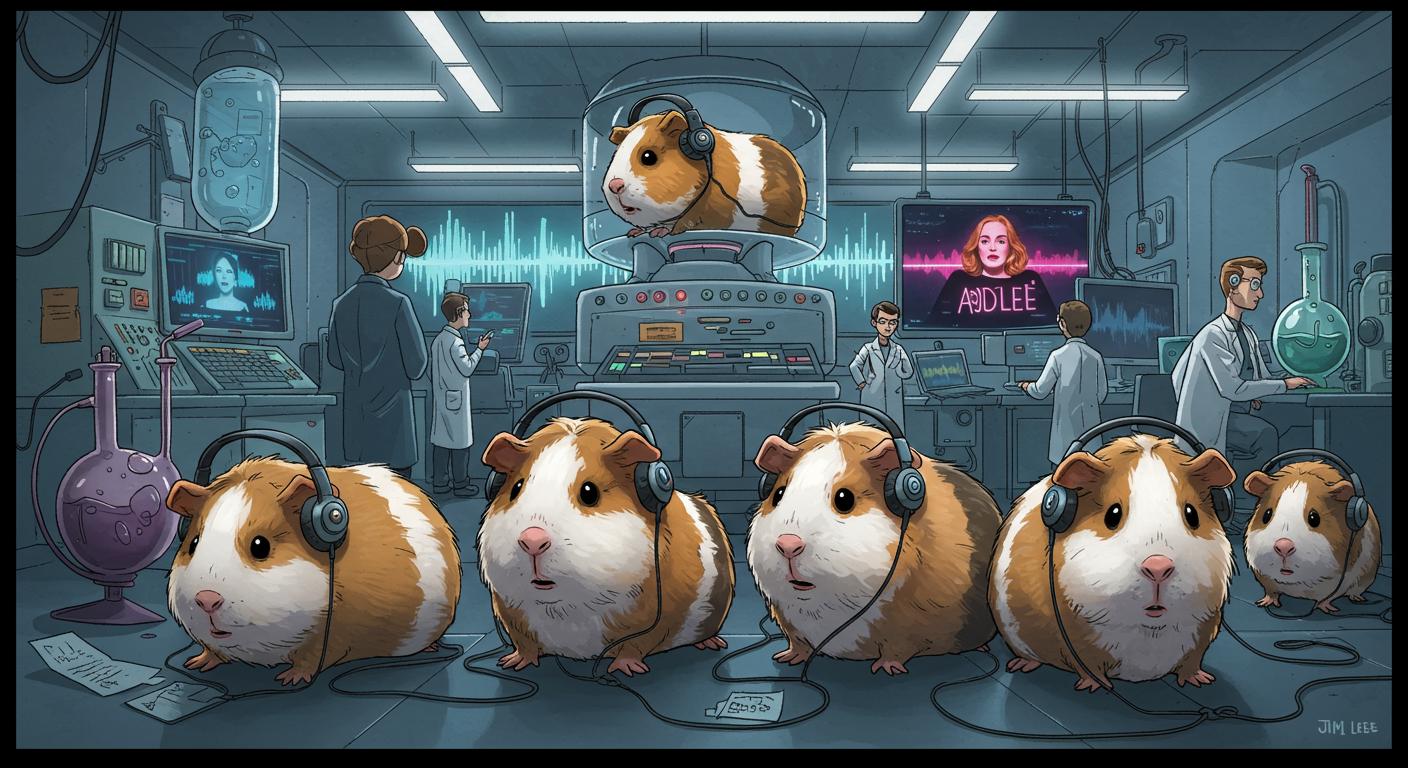

Most of us have sung along to Adele at least once—badly, boldly, or both—usually believing our renditions are a private affair. But while her music might bring humans together in living rooms and late-night karaoke bars, it recently brought a group of guinea pigs together inside a laboratory, where things got unexpectedly peculiar.

The Unlikely Intersection of Pop Ballads and Rodent Science

As set out in a MusicRadar report on a recent Pasteur Institute study, scientists undertook what can only be described as an unusually creative experiment: subjecting actual guinea pigs to Adele’s “I Miss You” for an entire week, played at a steady 102 decibels—a volume typically reserved for the edge of live music safety guidelines. For variety (if you can call it that), half of the rodents listened to the song in its original, uncompressed glory, while the other half endured a version squashed flat by audio compression.

MusicRadar’s coverage places this experiment in the broader context of debates around compression—audio processing that’s been alternately praised for rescuing limp recordings and blamed for the so-called “loudness war” that’s left decades of music sounding less dynamic. The outlet references compression’s dual reputation as both a studio lifesaver and a potential scourge: while it boosts the quiet parts and flattens peaks for a more radio-friendly sound, there’s an ongoing industry grumble about whether it comes with hidden costs to listener health—or, as in this case, guinea pig well-being.

Inner Ear Mayhem: Small Muscles, Big Problems

Results from the weeklong listening session took a curious turn once the scientists weighed up the guinea pigs’ ears for signs of trauma. According to MusicRadar’s recounting of the data, all of the animals experienced some temporary cochlear impairment, though those who heard uncompressed Adele made full recoveries within just a day. Their stapedius muscles—the minute structures responsible for dampening loud noises—regained normal function as if nothing much had happened.

However, the group subjected to the compressed version didn’t bounce back so easily. Described in MusicRadar’s summary of the findings, researchers discovered that the compressed track left the rodents with lasting reduction in their stapedius reflexes—down to half their strength after a week, and notably weaker than baseline. This outcome arrived despite both groups being exposed to music at the identical loudness level. Earlier in the report, it’s mentioned that the stapedius muscle measures just one millimeter in length—truly small, but apparently not immune to the relentless flatlining of pop production.

In a detail highlighted by MusicRadar, the root problem wasn’t just loudness itself, but the non-stop, unvarying onslaught of compressed sound. Referencing audiologist Paul Avan’s analysis published in Hearing Research, the article outlines how compressed audio overstimulates the nerves responsible for auditory processing, exhausting these tiny muscles and reducing the ear’s ability to recover.

Why Silence (or at Least, Less Compression) Matters

It’s perhaps unsurprising that guinea pigs forced to listen at near-concert levels fared badly, but the difference in recovery between compressed and uncompressed listening is what prompted researchers’ concern. MusicRadar notes that—unlike noise-related fatigue, which is widely recognized among musicians and studio professionals—compression’s effects hadn’t been clinically isolated like this before. The outlet also emphasizes the broader implication: even at the same perceived volume, relentless compression can be physically more punishing than recording dynamics that leave room for quiet moments.

The brain, and by extension the ear, apparently craves variation and space; the article relays Avan’s conclusion that silence between sounds gives auditory systems critical moments to reset and prep for the next barrage. Without those gaps, as the guinea pigs’ lingering impairment suggests, the constant sensory input can wear down resilience in ways the animals (and perhaps humans down the line) can’t easily repair.

Questions From the Quiet Bits

This raises a series of questions still hanging in the wings: How much audio compression is too much? Would different musical genres inflict the same damage, or is “I Miss You” now inadvertently a scientific cautionary tale? Could longer rest periods reverse the observed effects in the afflicted guinea pigs, or does dynamic range act like a sort of auditory sunblock—protecting us from more than we realize? MusicRadar remarks that these remain open avenues for future research, though the outcomes so far are unambiguous: uncompressed music, for all its quirks, exacts a far gentler toll on the ears than its dynamically quashed counterpart.

In the battle between unrelenting wall-of-sound pop production and a little quiet space, the humble guinea pig has unexpectedly become our stand-in. The next time a playlist serves up a string of tracks with the same unyielding punch, it’s worth asking: Are our ears quietly longing for a breather—and if so, what would a guinea pig recommend?